by Beatrice Bruni

_

“May the gods be with him together with the angels from all religions from all over the world, that he photographed so passionately”.

These are the moving words of farewell of the president of the Magnum Photos agency Thomas Dworzak over the death of his friend Abbas, Iranian photographer and member of the most famous photo agency in the world for four decades.

Abbas Attar left this world, which he had been able to tell so profoundly with his images, about a year and a half ago, in April 2018, in Paris, where he had always lived and worked. At Magnum’s, he was considered a pillar by all the photojournalists of the world, a figure of reference, a great authoritative father.

As the journalist Michele Smargiassi has capably written on his blog Fotocrazia, in perfectly timed homage following the death of the photographer, Abbas was a bit hastily considered the photographer of the Islamic world. It is sufficient, however, to consider the many different countries where his prestigious career unravelled to understand that he certainly dealt greatly with Islam, but he was above all a photographer of religions and history, and of the intersection of religion with history, politics and society.

His reports, from the beginning in the United States, in New Orleans, have in fact told the most important stories of the short century, its revolutions, its social and political upheavals, its wars. His are works on Biafra, Bangladesh, Northern Ireland, the war in Vietnam, the Middle East, Chile, Mexico, Cuba, and South Africa during the apartheid period.

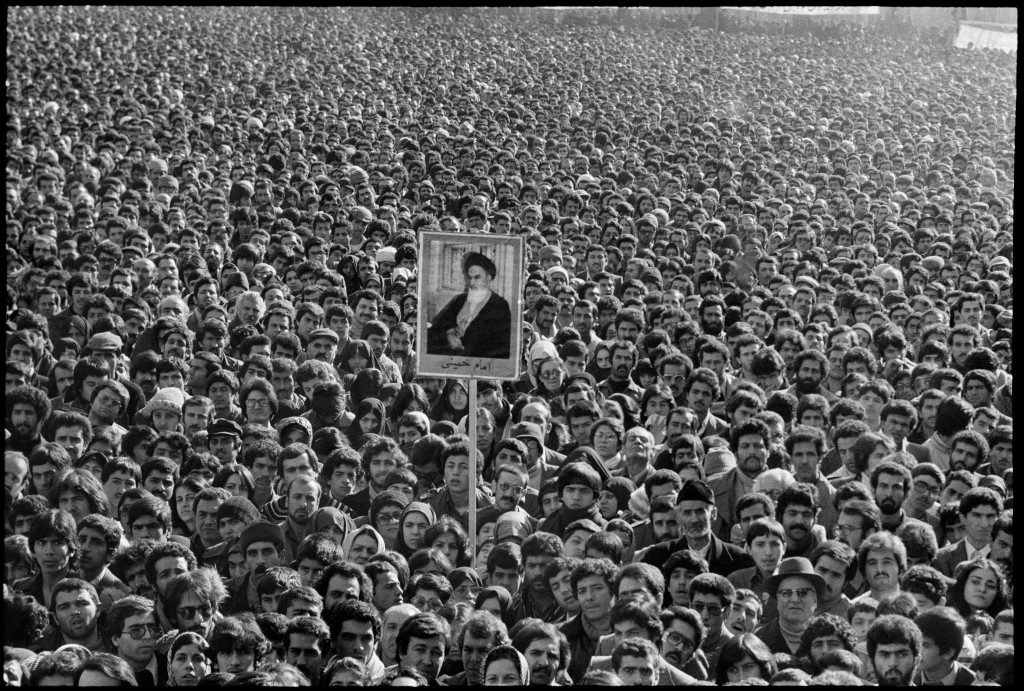

Abbas believed in a coherent personal style, in a real method that, in reference to his work, he defined as the capture in the image of a “suspended moment”. I don’t think that in the photographs of Abbas it is always easy to perceive this suspended moment. The photos of the Iranian revolution, for example, exhibited at the Palazzo Ducale for the 2019 edition of Photolux Festival, tell, on the fortieth anniversary of the event, of a very heated revolution, with the descent of huge masses of men and women in the squares.

In 1979, with the overthrowing of one of the oldest monarchies in the world, the Iranians won the first modern Islamic revolution. It was a revolution that us westerners struggled to understand. Iran appeared as a country just beginning to open up towards technological and social progress. This opening, however, was only superficial, given that the country lived under a repressive regime led by Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Persia.

The sovereign lived in the most unbridled pomp: his self-coronation was memorable, with his crown studded with enormous precious stones; famous was his close relations with Western socialites, his love for luxury and power and the economic relations with the United States and Great Britain. All this while his people were starving to death.

In order to make Iran the most important country in the Middle East, Pahlavi employed a great deal of state resources for the establishment of a strong army and for a continuous celebration of the monarchy. Modern and pro-Western politics meant that the Shiite clergy was not in favour his work. It must be considered that around 10% of Muslims are Shiites, so Shiism is definitely a minority branch of this religion, but most Shiites are actually in Iran.

To a few steps towards modernization, limited however to an increasingly narrow elite, the Scià responded with violent repression, like the obligation for women to take off their veils – his soldiers were sent to the countryside to tear the veil off the peasant women -a “modern” gesture of fierce violence. At the same time, women were not granted the right to vote. These and many other strong contradictions, like the close collaboration with the United States, for obvious strategic reasons, led to the growth of discontent among the Iranian population, also subjected to torture, arrests and killings of opponents. A situation that could not lead to a real revolution.

The plot of this event was designed by an extremely charismatic figure who, from his Parisian exile, led the Iranians to a new Iran: Ayatollah Khomeyni. An extraordinary personality capable of connecting all the forces opposed to the Shah, both religious, indeed the Shiite, and political with a Marxist trait. In 1978, when the first major protests against the regime began, Abbas immediately went to his country to document what was happening.

The beginning of the Iranian revolution, rather complex politically and perhaps not yet known in all its nuances, led to Pahlavi’s withdrawal abroad and above all to Khomeyni’s return from the Parisian exile. It was Abbas who took the photograph of Ayatollah Khomeyni as he descends the ladder of the Air France plane which took him back from Paris to Tehran as a winner. In that photo there’s all the destiny of Iranian people. Khomeyni established the Islamic Republic of Iran; all that was anti-nationalist and pro West was banned.

Abbas, who initially felt he was supporting the revolution against the absurd tyranny of the Shah, realized very quickly that violence was on both sides: with rigor and courage he also photographed “the dark side” of the revolution, refusing to leave unpublished the photos showing the revolutionaries “doing the wrong”.

In April 1979, Iran became, with a referendum, a theocratic, anti-Western totalitarian republic, led by Khomeyni as its supreme leader.

The violence unfortunately continued, under the determined eye of Abbas, and reached its peak in November when a violent riot, led by the Iranian students, led to many American citizens and diplomats being held hostages inside their embassy. The main request of the rioters was the extradition of Pahlavi, who fled to America. President Carter refused to accommodate the request.

A cinematic note: Argo, the film by and with Ben Affleck, winner of three Oscars including the Best Film Award, tells the daring escape of six hostages taking refuge in the home of the Canadian ambassador under the guidance of the agent of CIA Tony Mendez. A compelling true story, that tells efficiently of the atmosphere in the country and the international tensions that this whole affair had unleashed.

Not least was the start of a new era for the whole world: the President of the United States of America Jimmy Carter lost the elections, also because of the crisis of the American hostages in Iran. He had in fact promoted a rescue attempt that had a disastrous ending. Republican competitor Ronald Reagan was elected as the new POTUS.

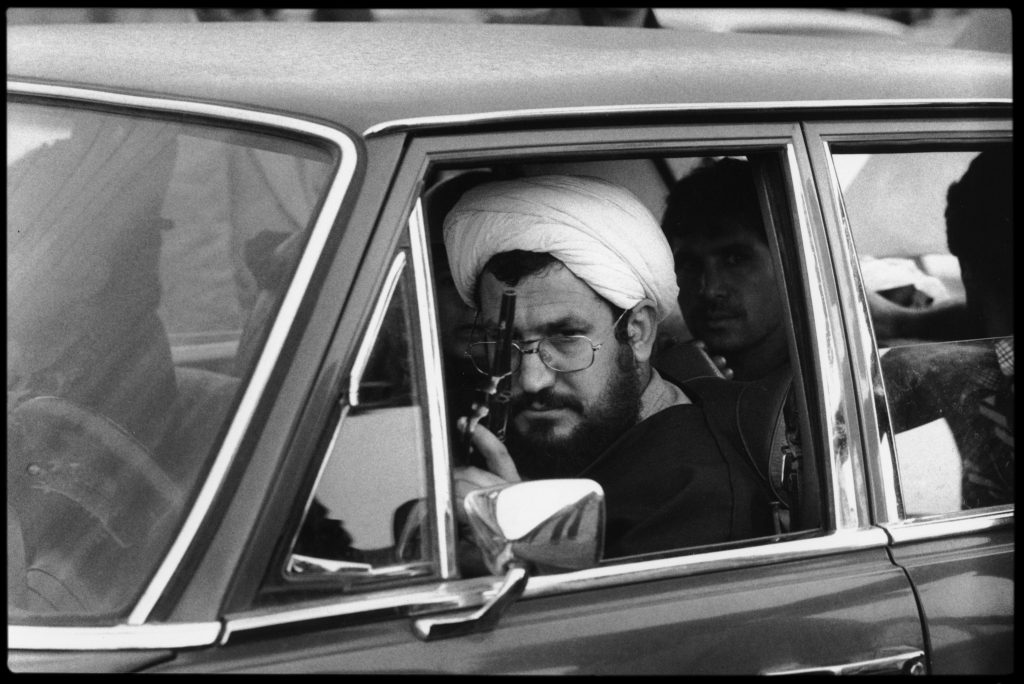

Abbas left Iran in 1980 and did not return for seventeen years. His first publication, in 1980, was La Révolution Confisquée, The Confiscated Revolution. On the cover of the book we find a very eloquent image: a mullah, driving a luxury car, looks into the camera proudly holding a weapon, on the day of the victory of the revolution, 11th February 1979.

ABBAS | THE IRANIAN REVOLUTION 1979

curated by Enrico Stefanelli

in cooperation with Magnum Photos

Palazzo Ducale

Cortile Carrara 1, Lucca

PHOTOLUX FESTIVAL | 16 November – 8 December 2019

from Mon to Fri: 3:00 – 7:30 pm

Sat and Sun: 10:00 am – 7:30 pm

November 15, 2019