di Daniela Tartaglia

_

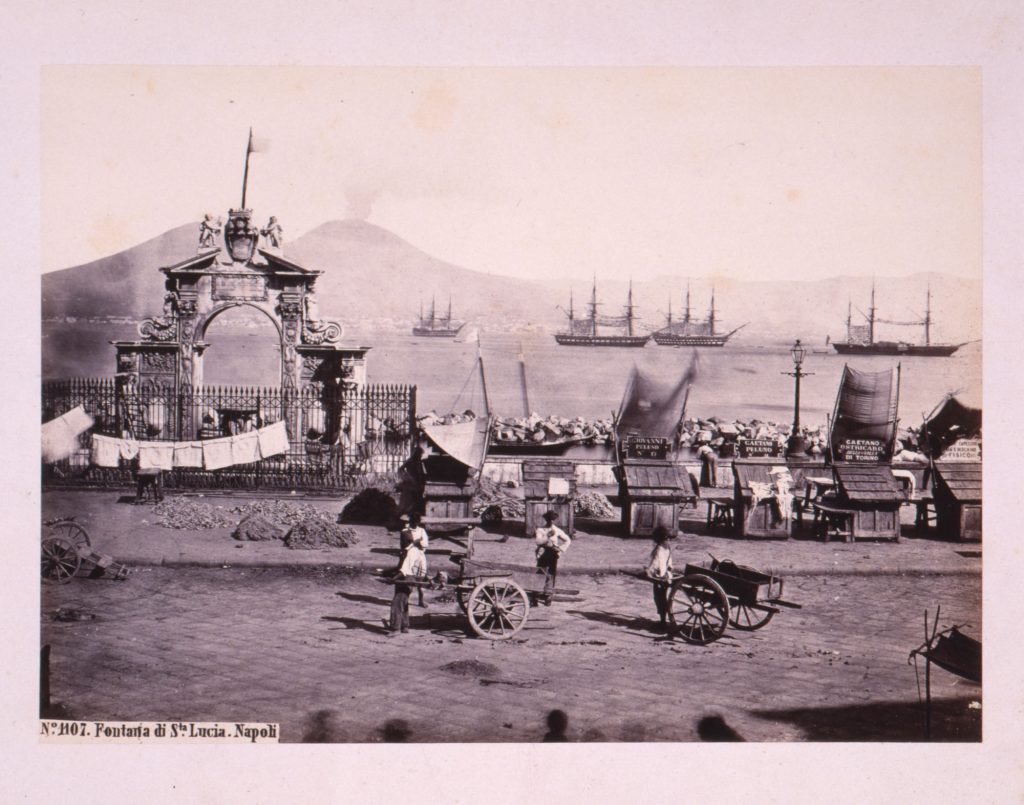

Photography, since its invention, has supported the need for human beings to document and leave a trace of their presence in the world. With its immediacy and the ability to show and capture everything, even the smallest detail in the visual cone of the camera, during the nineteenth century it quickly won over archaeologists, painters, geologists, naturalists and above all travelers, of whom it became a precious and useful companion, able to capture “places which were distant and impossible to reach”.

It was, simply, a valid and easy-to-use precision instrument, an alternative to the camera obscura and the camera lucida traditionally used by travelers and painters to draw monuments or landscapes of which they wanted to keep the memory.

Born from the secular soul of the Enlightenment movement, photography has established, from the very beginning, a very close relationship with the world of exploration and travel. A journey that, starting from the mid-eighteenth century and throughout the course of the nineteenth century, no longer was prerogative of merchants, pilgrims, aristocrats, diplomats or members of the future ruling class but it opened also to intellectuals, writers, artists and musicians. (C. De Seta, 1997)

Citizens of the world and offspring of the productive bourgeoisie, the nineteenth-century intellectuals toured Europe, the Mediterranean and the Near East, driven not only by the need to get to know countries and civilizations other than those of origin, to become familiar with trades and models of efficiency in the management of the State, but mostly driven by intellectual curiosity, addressing the theme of travel as an experience of cultural, personal, emotional as well as professional training.

As an irreplaceable parameter for comparison with reality and a new way of looking at and experiencing space, newborn photography in 1839 was enthusiastically presented to the public by François Arago, scientist and deputy from the Eastern Pyrenees, at the Académie des Sciences and the Académie des Beaux-Arts of Paris with these words: “Who would have believed, a few months ago, that light, being penetrable, intangible, imponderable, literally devoid of all the properties of matter, would have taken on the task of the painter by drawing itself, with the most exquisite craftsmanship, those ethereal images which it woud have painted fleetingly in the darkroom and which art tried in vain to arrest? Yet this miracle took place in the hands of our Daguerre.”

And again: “To copy the thousands of hieroglyphs that cover the great monuments of Thebes, Memphis, Karnak, it would take twenty years and legions of draftsmen. With the daguerreotype, only one man can carry out this immense work without errors.“

Photography is therefore part of a culture which, starting from the Renaissance, had had an extremely positive attitude towards technology and which, already in the seventeenth century, had seen important steps taken in the “mechanization of thought” (D. Mormorio, 1997) with the calculating machines of Pascal and Leibniz.

In the Nineteenth century – the so-called “century of modernity” – characterized by important progress such as artificial light, the circulation of information in the press, new railway lines and the use of increasingly faster means of transport, the combination of travel and photography will become a fundamental element in the exploration of the world and in the construction of national identities.

The English photographer Francis Frith wrote in 1860 for the British Journal of Photography: “Nothing can replace the real journey, but it is my ambition to offer those who are not allowed this pleasure faithful representations of the scenes of which I was a witness, and I will make sure that the veracity of the photograph guides me in writing.“

Cradle of myths and history par excellence, the Mediterranean, since the early years of the invention of photography, became one of the favorite destinations of travelers and also one of the favorite subjects of photographic representation. In November 1839, just six months after Daguerre’s announcement, the painter Horace Vernet arrived in Egypt with Fréderic Goupil-Fesquet to carry out the first photographic documentation campaign. By the end of the year, the daguerreotype documentation of Jerusalem was also completed, followed by that of Nazareth and Acre.

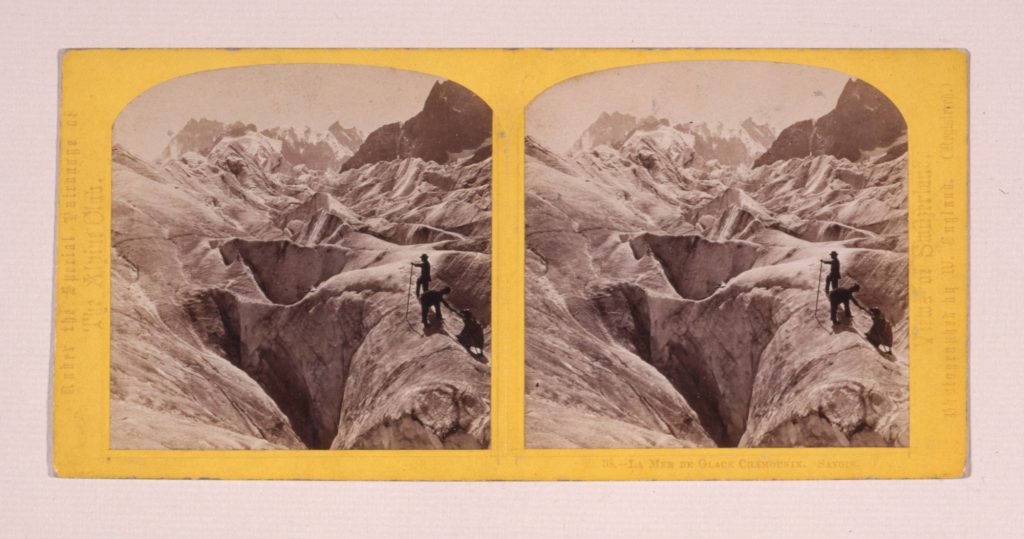

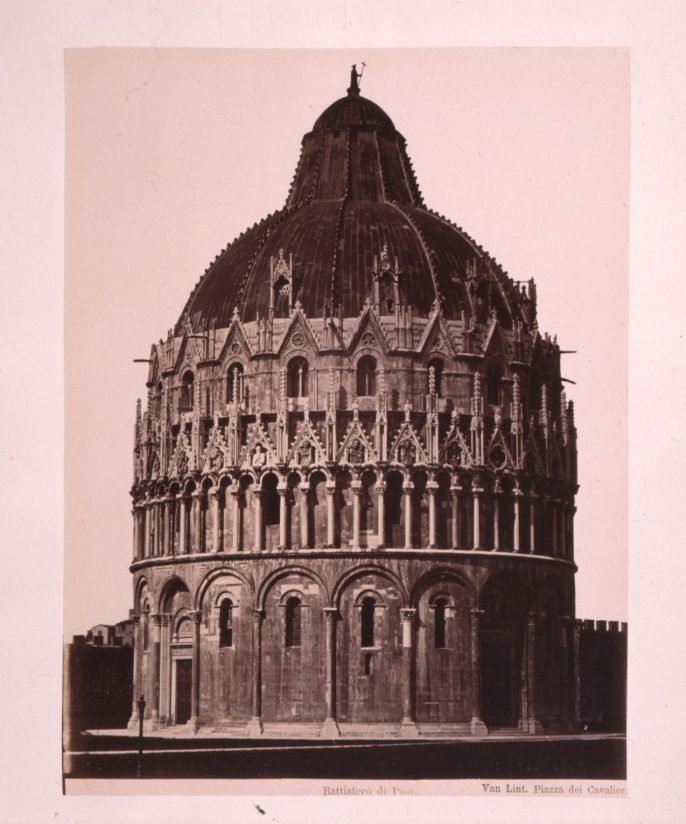

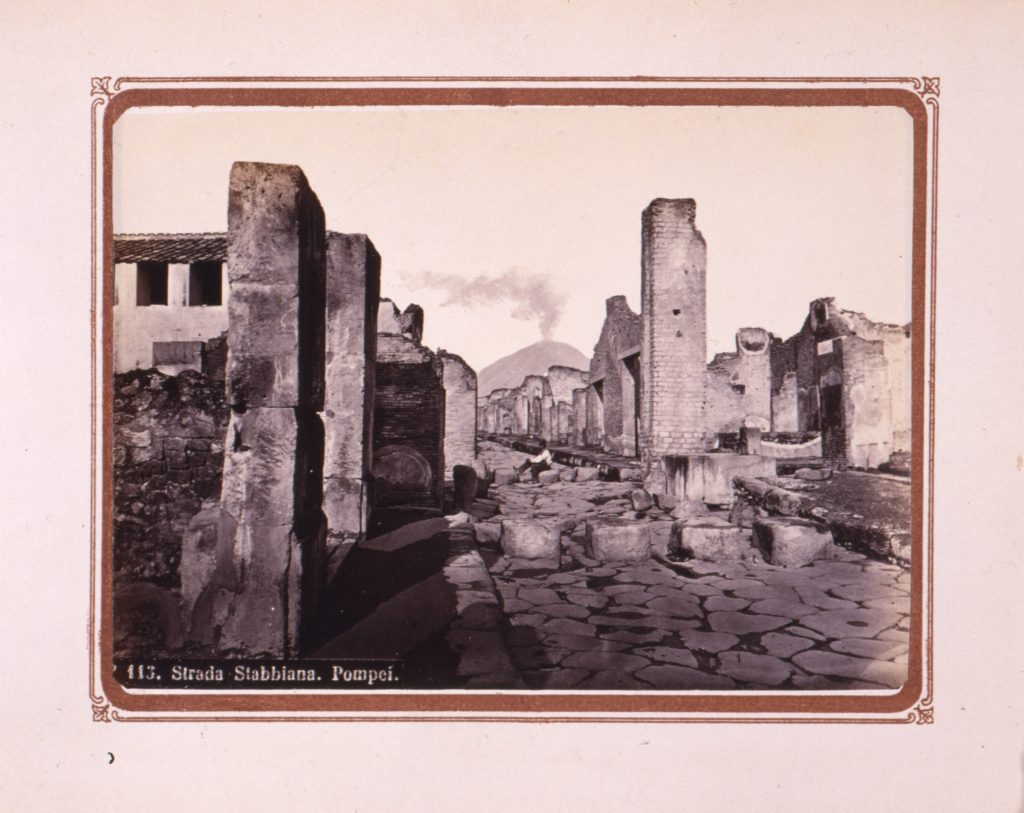

Thanks to new technical procedures including collodion on glass plate and positive albumin printing, the blooming photography industry immediately understood the need for exoticism, remoteness and visible testimony of travelers and the bourgeoisie of the time, producing thousands of photographs, cartes de visite and stereoscopies, made by the major European professional photographers of the second half of the Nineteenth century (Maxime Du Camp, Francis Frith, Antonio Beato, Felix Bonfils, Giorgio Sommer, Robert Rive, Giacomo Brogi, Leopoldo Alinari and many others ) that illustrated every corner of the world from the Alps to Egypt, from Venice to Palermo to Palestine, Turkey, Greece and Spain.

In the thousands and thousands of photo albums that travelers were going to compose upon their return from their explorations, they would put photographic images purchased in the ateliers that the great professional photographers had opened in almost all the main European cities, in response to the generalized use of photography by an increasingly large audience.

The Nineteenth-century photo album was itself a journey, a mental itinerary made by the person who had assembled it by mixing images of landscapes and fine architecture with precious handwritten annotations, dates, impressions and daily journals. We can compare it today to a practice of construction of individual and collective memory, to one of the first bricks in the construction of the “global village” to use the definition that McLuhan will create in the 1960s.

The extraordinary iconographic heritage contained in photo albums that survived brings to mind a longed-for past now gone forever, the memory of a Mediterranean and a Near East, beautiful and metaphysically empty, suspended in time, dissolved but still capable to renew the myth and the very notion of travel.

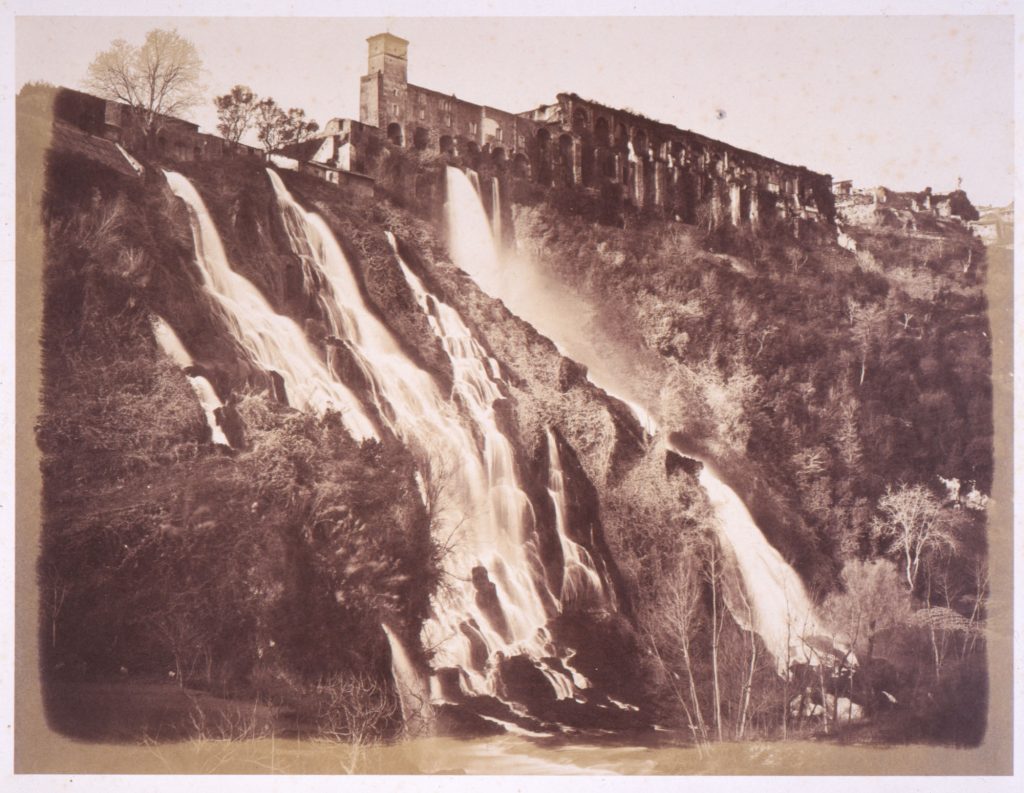

The photographers of the nineteenth century, despite their cataloging mania that gave us rigorously frontal and clear images, actually knew how to keep a contemplative attitude towards the object of their photographs, a sense of wonder, of surprise, and how to give back a unity that came from the perspective vision of the Renaissance but also and above all from the patience with which they fed their gaze in order to understand the complexity of the surrounding world.

Consciously or unconsciously, these images had a connection with the silence of places and still manage to establish contact with a notion of time that no longer seems to belong to us and that, in a way, we would like to recover.

It was a slow journey that the photographers of the nineteenth century made: an approach and a discovery of a place that often happened overcoming great difficulties, after long, uncomfortable journeys, transporting equipment on the back of a mule or camel, having to deal with heat, dust and lack of water. Often the outcome of these expeditions was uncertain and the photographer had to fight with a hostile nature, with boiling collodion emulsion, with insects.

In his memories (1882) Maxime du Camp describes his approach to the photographic technique in the journey to Egypt, Nubia, Palestine, undertaken together with his friend the writer Gustave Flaubert: “Photography back then was not what it became later, there was no glass, collodion, quick fixing, instant operation. We were still dealing with the wet plate process, a long, meticulous process that required great hand skill and more than forty minutes to complete a test. Whatever the strength of the chemicals and the lens used, to obtain an image, even in the most favorable light conditions, an exposure of at least two minutes was required. However slow this process was, it represented an extraordinary advance over the daguerreotype plate which presented objects flipped over and whose metallic lustres often prevented the image from being visible. Learning to photograph was a trivial matter; but carrying the equipment on the back of a mule, a horse, a man was a problem. At that time there were no gutta-percha vessels; I was forced to use glass vials, crystal bottles, porcelain bowls that could accidentally break. I had cases made as if they were for the Crown Jewels and, despite the unpreventable impacts when travelling, I managed not to break anything and I was the first to bring back to Europe the photographic evidence of the monuments saw in the East.” (D. Mormorio, 1988)

With the advent of the Twentieth century, photography rapidly lost these complex implications with the metaphysical space to increasingly confront the changes in the social fabric, science, anthropology and the birth of psychoanalysis.

The architectures in their monumental isolation are now contrasted by the animated urban views taken by travelers and amateur photographers who can rely on small-format portable devices, on gelatine plates with silver salts for immediate use and subsequently on roll films, industrially made and easy to use. Architecture and landscape cease to be the true protagonists of the image and become a stage on which the men and women of the twentieth century joyfully acted their “human comedy”. Unprecedented well-being and civilization form the backdrop for balloon trips, exotic travels, boat and mountain excursions, beach holidays, with which the bourgeoisie of trade and professionals, together with the new middle class of teachers and employees, celebrates the industrious and peaceful era of the Belle Époque.

However, becoming the prerogative of many, the production and use of images end up profoundly modifying the collective imagination and the very concept of experience. The enlarged circulation of sensory and intellectual stimuli, outside personal experience – brought about by photography first and then by cinema – will contribute to the liberation of large masses of people from what sociologists call the “tyranny” of individual experience.

Hosted more and more consistently on the pages of magazines, the photographic documentation of the trip (and more) will have a very strong social impact, comparable only to that introduced by Gutenberg’s printing process. The impact will be such as to guide the existence of great masses of people, anthropologically and culturally, enriching the “global village” with levels of universality and homogeneity never reached before but, at the same time, profoundly modifying the function and quality of the sources of production of the collective imaginary.

March 29, 2021