by Dario Orlandi

_

“Photography cannot lie, but liars can photograph”.

With this aphorism – the “postulate” that Lewis Hine formulates in 1909 – Michele Smargiassi introduces the occasion that led to the drafting of Un’autentica bugia [An authentic lie] one of the most interesting and complete essays of recent years on the ambiguous dialectic between the nature of the index/document of the photograph opposed to its ability to lie.

For Hine, the photographic lie cannot be attributed to the medium, but only to the exploitative use of “liars” photographers.

But is it true that photography cannot lie? The author helps us with the reflection. How can an instrument – though mechanical – whose nature consists in isolating portions of space and time and reproducing them on a flat and static surface be taken as a tool for representing reality? And what about the mystifying uses of photography by photographers? Are they necessarily intentional – and therefore condemnable – or fortuitous and unconscious, therefore less identifiable and less blameworthy? And even if they were intentional, when they are truly reprehensible or when they deserve – at best – a loving pat?

In its central part, the book brings us a deep and widely documented phenomenology of photographic lying. A catalogue of when, how much, how and why photography (which photography?) “Always lies, lies by instinct, lies because its nature does not allow it to do otherwise” (Fontcuberta).

Two young girls claimed to be able to capture fairies: a hoax that misled even Conan Doyle. The “supernatural creatures” visible in the image were actually scraps of illustrations arranged on the scene, the authors admitted in 1982, more than half a century later.

If it is true that every photograph affirms a “been there” (Barthes) it is equally true that in the production processes of the image the intermediate steps, more or less intentional, are many and highly distorting: from the mechanical / material nature of the medium to the choices of the shooting, processing, edition and publication phase.

The technological quality – asks the author – affects the level of unreliability of photography? Some critics believe that the numbering of recording / filing processes has led to a dematerialization of the referent-image contact that has weakened – if not completely abolished – that physical / material bond that united object and representation (Mitchell, Ritchin). It is also true, however, that even in analogue terms the documental function of photography rests on the awareness of the index nature of the medium: “photography produces icons of truth only because it collects indices, imprints of real objects; and I know it. […] And this is true whatever the technique used to collect the imprint “.

Photography, therefore, lies regardless of the chemical or numerical nature of the support.

It lies – we quote freely from the text – because if on one hand photography is a “message without a code” (Barthes), unable to deny the truth, it is nevertheless capable of “affirming the false”.

It lies because every mechanism is a “frozen will” (Flusser) that brings within itself the “technological unconscious” (Vaccari) of the cultural macro-context of production. It lies because every “denied image” (not shot) is a consciously or unconsciously intentional removal of the continuity of reality. It lies because every context produces genres and stereotypes that inevitably condition the production of images. It lies because the frame, the grain, the perspective ratio, the lighting and staging are forms of alteration of reality, through their specific technical mean. It lies because photographic freezing transforms an instant – transitory by definition – into an infinitely persistent monument. It lies for intentional manipulations as for that carried out in good faith. It lies for the way, the sequence, and the context in which it is presented. It lies because there is no “aboriginal glance”, untouched by individual and cultural conditioning in the very act of receiving the image.

Photography – in short – is an “alibi”, an instrument with which “we produce images that justify a posteriori our precarious beliefs about the world.”

And we do this for our natura ludens, or because we take advantage of it, or because we want to be reassured by bringing the images back to our expectations. In a nutshell because “we prefer images to reality” (Levi Strauss).

A military venture: the conquest of the Japanese island after a long battle. The photographer missed the crucial moment of the flag-raising ceremony, but he was lucky. The precious flag was lowered shortly after, upon request by an officer who wanted it as a relic for a museum. A second one was then hoisted, which Rosenthal photographed, creating a symbolic image that earned him the Pulitzer and became one of the most famous photographs in history.

Photography is therefore a contemporary “Cassandra”, which “sees even more than the first one”, but – unlike its ancestor – “is not at all sure of what it sees”, despite the positive society has assigned it the “task, denied for centuries to other arts, to provide evidence that the world is really how we see it.”

What can we do with this new and specular “anti-Cassandra”, of this elusive instrument – for its technical and technological nature – and subject, despite the expectations of adhesion to the real, to be a vehicle of conscious or unconscious mystification, in good or bad faith? We must naively claim its purity, the “immaculate perception” – wonders with a witty wordplay – or else repudiate it as a traitor?

Deception is the characteristic of someone who “plays his game with shrewdness because it is the best tool he has to achieve his goals”. But to deceive is not to betray: betrayal is the “cowardly gesture of someone hitting a friend who loves him and trusts him”. The Trojan horse is not the kiss of Judas, paraphrasing Fontcuberta

This is the only case in which photography commits a mortal sin, the only unforgivable one: when it produces, intentionally and productively, “false testimony”.

Therefore, photography cannot be asked “more than it is able to give”. It is an “incessant liar who is obliged to say at least a portion of truth if questioned in the right way.” When treated with kindness, photography gives “little unasked truths.” This touch, “this unintended residual is the true photographic specific.” A “marginal and accidental accumulation of truth, insensitive to the connotations imposed from the outside, that is the prodigy of photography”.

Photography is therefore an “indexical icon”, a semiotic oxymoron that condemns the photographic image to a Middle-earth between document and picture. But precisely in this suspension photography finds its power of extraordinary – perhaps the most extraordinary – metaphor of modernity.

Fluidified and liberated from historical polarizations, modernity is not for extremes “iconodulists” nor “iconoclasts”, but for those who are able to “listen carefully to the mermaid song, [remaining] firmly tied to the mast of the ship”. For those who – summarizes the author – are able to recognize lies, use them as a tool for analysis, measure their level, negotiate in a laic and conscious way the truth within the triad author-user-context.

The reflection on the mendacity of the photographic truth is for Smargiassi a rich opportunity to exercise one’s critical skills, for the development of a complex form of awareness able to dialogue with the multiform and ever changing contemporary reality: “any trust in the ontological truth of photography is now destroyed forever. It is therefore time to transfer the burden of truth from the weak shoulders of the medium to the strong rationality of the user, who is the authentic constructor of the meaning of the image, and is so much more effective the more he is aware of it.”

*Editor’s note: with this short text we tried to synthesize a dense and wide volume, trying – as far as possible – not to sacrifice its complexity. Conscious of the inevitable limiting effect of the operation, we tried to maintain the sequence, the topics and the fundamental ideas, the final reflections, reworking them freely in the form, hoping to offer an adequate content.

In inverted commas, the direct quotations from the author; when coming from other authors their name is indicated in brackets; in italics all concepts that, even if not specifically expressed in that form, are present in the text.

The book:

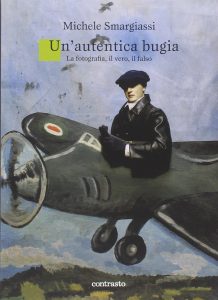

Michele Smargiassi

Un’autentica bugia: la fotografia, il vero, il falso

Contrasto, 2009

December 7, 2018