by Daniela Tartaglia

_

The exhibition The imprint of reality. William Henry Fox Talbot. At the origins of photography is underway at the Estensi Galleries in Modena. An extremely eclectic exhibition, rich of material that re proposes the relationship between William Henry Fox Talbot, pioneer of photography, and the distinguished Modenese optician and naturalist Giovanni Battista Amici. The English photographer was a client of the latter: in the summer of 1839 he had sent him 18 images on paper, photogenic drawings and calotypes, made five years earlier, hoping that Amici would help him to claim the antecedence of his discovery at the upcoming congress of Italian scientists in Pisa. William Henry Fox Talbot had seen fit to establish an alliance with the illustrious Italian scientist to counter the fame of his rival Daguerre, the French painter and set designer who, in January 1839, through François Arago, had announced to the Academy of Sciences of Paris and the whole world the discovery of a method to spontaneously reproduce the images of nature, reflected by means of the “camera obscura”.

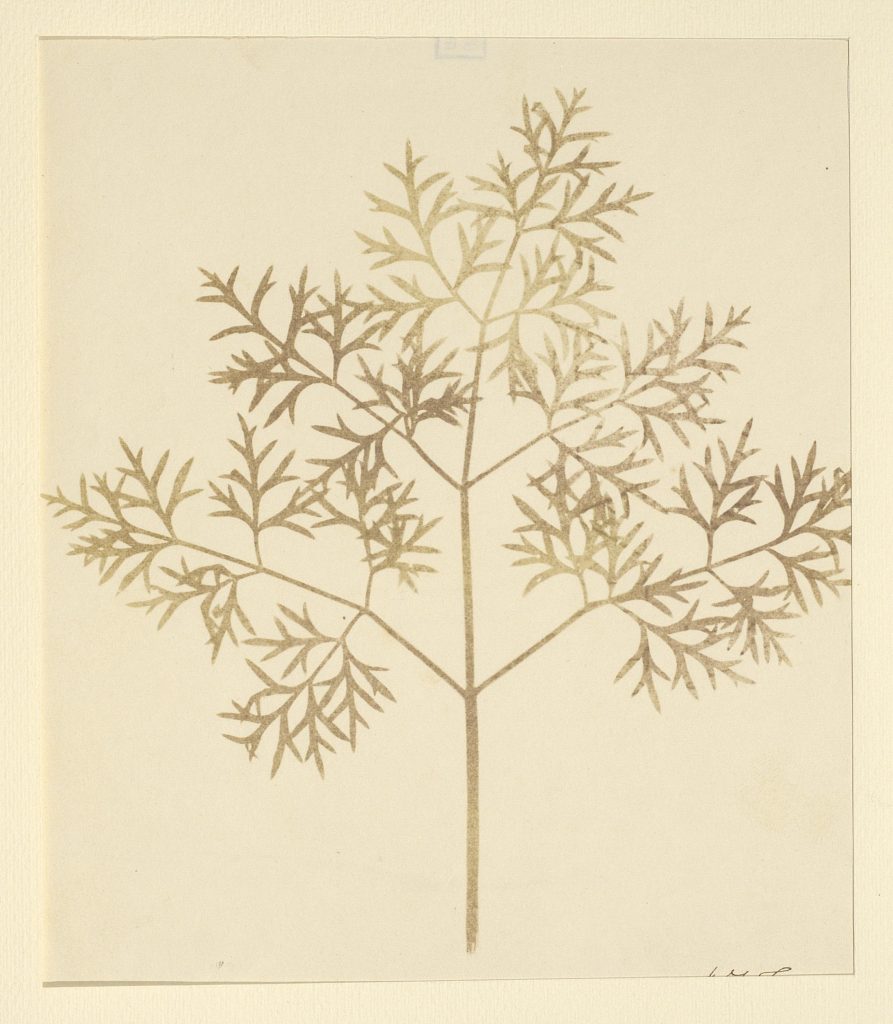

The exhibition combines the daguerreotypes, the priceless photogenic drawings and calotypes of Talbot, with the cyanotypes of his contemporary Anna Atkins, images with a characteristic turquoise hue, created by sensitizing the paper with ferric salts which, like silver salts, are sensitive to light. Alongside precious incunabula, letters, documents, and original instruments – the catadioptric microscope and the camera lucida built by Amici, for example – we also find twentieth-century and contemporary photographs that reveal stringent connections with early photography.

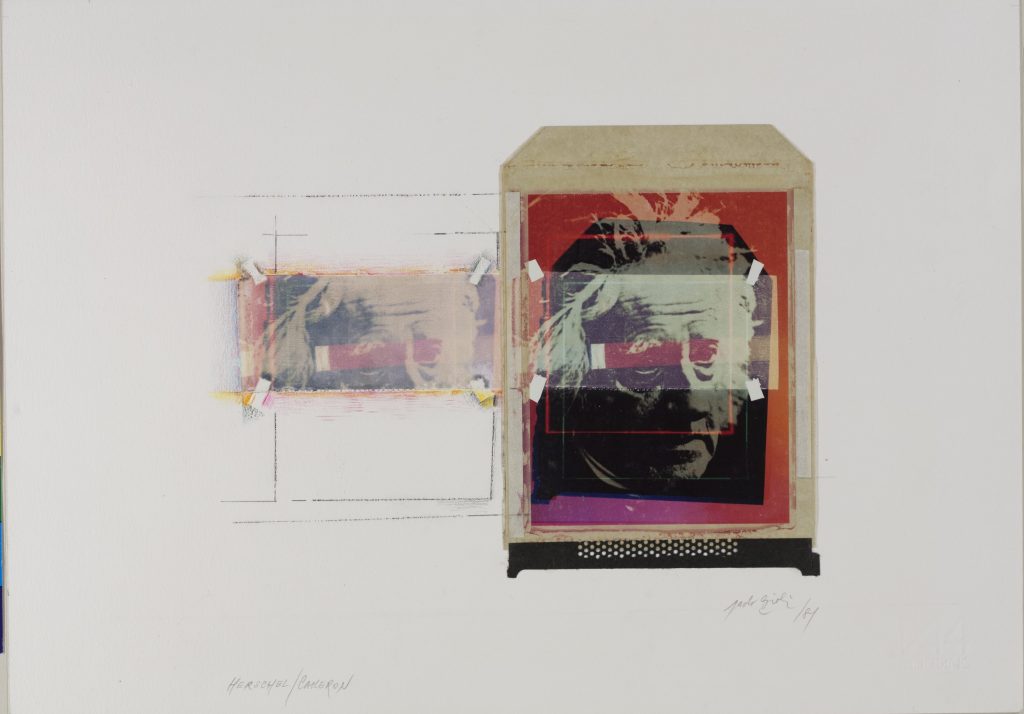

In a dialogue with the objects that tell the dawn of photography we can admire, in fact: the series of Polaroids (direct or transferred to other media) with which Paolo Gioli pays homage to the fathers of photography; Verification 7. The laboratory. One hand develops, the other fixes dedicated by Ugo Mulas, in the Seventies, to John Frederick William Herschel, inventor of sodium hyposulfite and also of the term photography (writing with light); the “off camera” experiments by Man Ray, Luigi Veronesi and Claudio Abate who, through the direct contact of objects or bodies positioned on the sensitive surface, record transparencies, thicknesses, lights, reflections in an anti-naturalist and anti-narrative way.

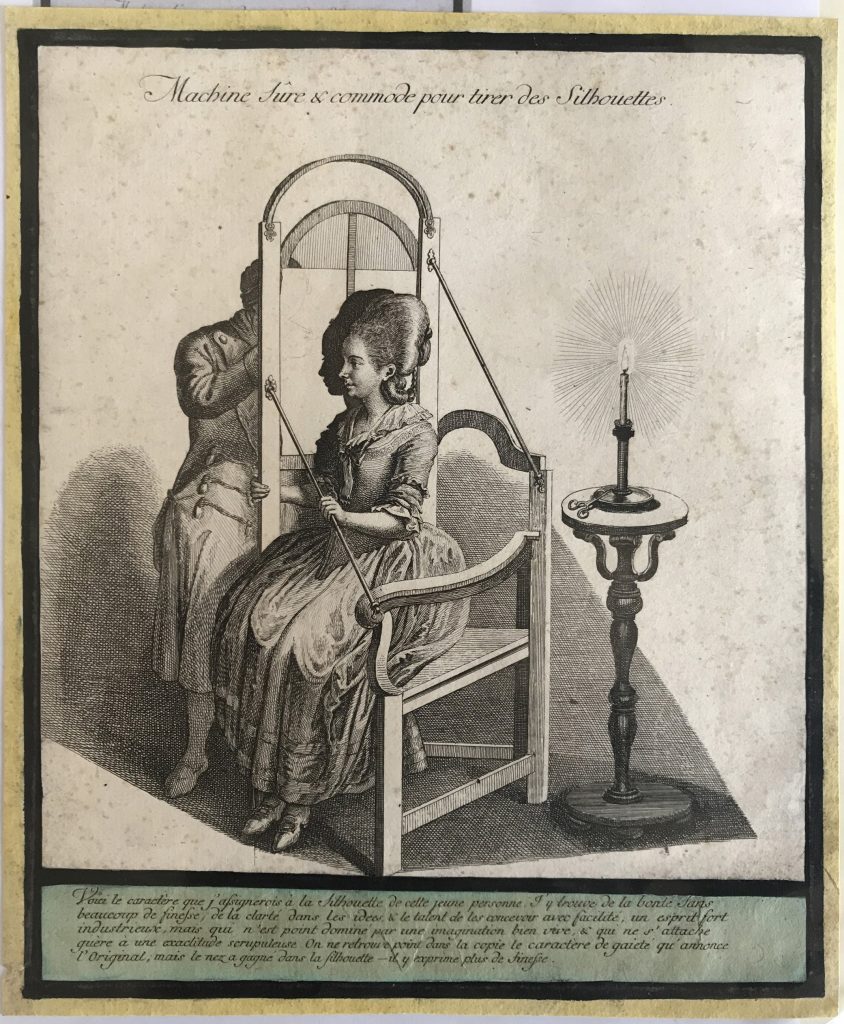

Very interesting is the first section of the exhibition which investigates the pre-photographic culture between the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century, all aimed at finding an automatic method of reproducing reality and using mechanical devices, designed to facilitate the copying of the subject: machine for silhouettes, camera lucida, Claude’s mirror. This section allows the visitor to reflect on the duality of reality and representation, inherent in photography, which has marked its entire history.

The exhibition clearly illustrates how photography, before being an image that reproduces the appearance of an object, a person or a scene in the world, is first of all a sample, a trace. And how this duality of representation/presence was already clear to William Henry Fox Talbot, pioneer of the photographic process to whom we owe the discovery of the latent image and the seriality of photography, its reproducibility and mass diffusion.

Talbot was in fact a very refined intellectual, aware of the aesthetic and socio-cultural implications of the new medium, so much so that in his book The Pencil of Nature (London 1844-1846), the first printed book with photographic images, he defines the photographic image an imprint and photography the art of fixing a shadow. It is no coincidence that he adopted for his works not only the term “photogenic drawing”, but also skiagram, literally “shadow drawing”. He therefore made his own the same concepts used in various texts to explain the origin of the drawing, discovered, according to most, by the potter Butades thanks to his daughter. Legend has it that the Corinthian girl, taken in love for a young man destined to leave for foreign lands, took the imprint of her beloved, drawing the outline of the shadow of his face, projected on the wall by a lamp. The father then made the bas-relief of the face by filling the outlined outline with clay (Roberto Signorini, 2007).

The curators of the exhibition – Silvia Urbini and Chiara Dall’Olio – have wisely highlighted, through countless contributions from different collections, the profound nature of the indexical device that will sanction the birth of photography: the instantaneousness of the shadow, outline, silhouette, surface of inscription, projection, light source, trace, imprint, duplication, materialization and fixity through a direct cast.

During the nineteenth century this value of sampling/trace, although belonging to the profound nature of photography, was overshadowed in favor of mimesis and descriptive intentions, of a positivistic matrix, which directed much of the photographic production on side of documentation and cataloging. In those years, photography played its game – or rather its “fight” with painting – based on the logic of the painting, of the canvas, of two-dimensionality, for a supremacy entirely internal to the concept of work as image. And in that confrontation photography did not always prevail, as evidenced by the fierce criticisms that, starting with Baudelaire’s contemptuous comments at the Parisian Salon of 1859, have always insisted on the mechanical and mimetic component of the medium to prove its inferiority, if not the absolute lack of artistry. To counter and exorcise the mechanical nature of the photographic medium, the nineteenth-century pictorialists used elaborate shooting and printing techniques, regaining their manual skills and thus highlighting a clear detachment from the “vulgarity of reality”.

Think of the composite prints of Henri Peach Robinson and Oscar Gustave Rejlander, the bichromate gum or carbon prints of Robert Demachy and Camille Puyo. In a logic, once again of enslavement with respect to painting, the pictorialist photographers played an entirely defensive game, without realizing the operational and conceptual innovations connected to the use of the photographic instrument. It was thanks to the revolution carried out by the artistic avant-gardes, Dadaism and Surrealism above all, in assuming the mechanical and automatic gaze of the camera as a stimulus or “model” of the profound spirit of making art, that photography could begin, without shame, to actually being itself, a machine that as such can participate in the aesthetic experience without necessarily having to wear paint (Claudio Marra, 2012).

The photographic act, in its deepest nature, is in fact an act of withdrawal from the visible reality, a sort of “Duchampian ready-made”. Through the act of photographing as a withdrawal from the visible reality, the photographer actually decontextualizes the photographed subject, investing the object of its withdrawal with a new meaning. But that’s not all: it freezes time in a vertigo of definitive immobility. Unlike the painter who captures time at every stroke of the brush and can afford, in theory, never to consider a painting finished, the photographer is instead faced with a unique and definitive choice. When he presses the shutter button he “cuts” time, with no more possibility of intervention. It captures the instant and makes it eternal, transforming evolutionary time into still time (Jean Christophe Bailly, 2008).

In this vertigo of definitive immobility and suspension of time, photography brings with it a part of the unknown, “the shadow of his psyche”. Indeed, the deposit/trace contains not only the visual unconscious, which was already intuited by William Henry Fox Talbot in the commentary on plate XIII of his The Pencil of Nature, but a sort of psychoanalytic unconscious, a suspension, a work of magic.

But as a factor of revelation, what does photography have the capacity to remember? What is the link that intertwines with memory? According to the fascinating interpretation of Jean Christophe Bailly, which in part continues the method of investigation used by Aby Warburg and her disciple, the philosopher and art historian Georges Didi-Huberman, photography not only realizes and actualizes the impossible dream of the young girl from Corinth to freeze the shadow of the beloved but, through the gap, the lack, the distance from the real, it works a sort of transfiguration that suspends the appearance in an almost ideal way: a web of invisibility crosses the visible and does so directly in the image, in its skin, like a tattoo.

This “underground concordance of attitudes” (Claudio Marra, 2012) between photography, Dadaism and surrealism contributed, among other things to changing the face and the outcome of artistic and aesthetic research during the twentieth century in a significant way, paving the way of photography to other possibilities and links, forcing contemporary artistic research to confront the conceptual identity of photography, with the exaltation of technological objectivity, the irrelevance of manual skills, the questioning of the concept of representation, the investigation carried out on the relativity of vision.

L’IMPRONTA DEL REALE

William Henry Fox Talbot. Alle origini della fotografia

curated by Silvia Urbini with Chiara Dall’Olio

catalogue published by Franco Cosimo Panini Editore

Gallerie Estensi

largo Porta Sant’Agostino 337, Modena

12 September 2020 – 10 January 2021

Tue – Sat: 8:30 am – 7:30 pm

Sunday and holidays: 10:00 am – 6:00 pm

The exhibition is temporarily closed to the public due to the Covid-19 emergency. While waiting for the reopening, virtual guided tours are being periodically organised.

December 18, 2020