di Dario Orlandi

_

I paesi parlano, come ogni cosa, e parlano innanzitutto con la geografia.

Sono terra da leggere anche se hanno perso molte parole, e da scrivere.

[Villages talk, like everything, and they talk primarily through geography.

They are land to read, even if they have lost many of their words, and to write.]

Franco Arminio

«Italy has a very long backbone that is gradually losing its lymph. People choose to live in cities and, when choosing towns instead, they always make sure they are comfortable and flat. Nobody wants to live in inaccessible places, where winters are long and nobody passes by. The Apennines is the Italy we used to have and which we risk losing forever. People have lived there for millennia consuming what little they needed to support themselves. I think of the Apennines as a real safe for the villages, a safe full of outdated currency.»

These are the words with which Franco Arminio – poet, essayist and “landscape expert”, as he likes to define himself – introduces Varco Appennino, the book that Simone Donati, photographer of the TerraProject collective, has dedicated to the mountainous ridge of southern Italy, an emblematic place of ancient culture and of frugal subsistence, of deeply rooted rites and collective memories, which the modern socio-economic transformations have changed significantly.

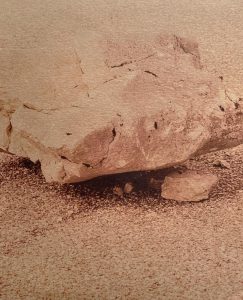

The Apennines as the backbone of peninsular Italy, in its environmental and cultural recurrences that are a lot more consistent than the ever-changing coastal realities. The Apennines not only as a geographical term, but as a “site” – in its very profound meaning of belonging – whose abandonment represents the slow and inexorable dissolution of a way of being together as topos and ethnos. The Apennines, finally, as the scene of clumsy attempts at a hasty modernization, a place of ” false modernity” which, as well as being forced, proved to be scarcely effective.

Donati’s images, slow and silent in continuity with the choice of language that characterizes the profound and reflective approach of the collective of which Simone is the founder, offer an insight into the sense of belonging and the rituals that mark the now desolate villages of the peninsular hilltops. In the cafes and in the semi-deserted streets, in the trattorias and in the hotels with a domestic taste, in the faces marked by sun and frost, the calls of the shepherds and the echoes of the bell towers resound to mark a silent and dilated time. The images are interspersed with Franco Arminio’s Vocabolario Appenninico [Apennine Vocabulary], a breviary of terms that probe the depth of the territory, its identity: “Bar”,”Farmer”,”Desolation”, “Emigrants”, “Places”, “Piazza”, “Silence”, “Old people” are some of the voices of this intense compendium that dialogues with the images along the pages of the book.

Arminio continues: «There are areas where the landscape is still uncontaminated and is as it should be: lonely and wasted. What to hope for these lands? Rather than asking for financial incentives, one would want to incentivize the exodus, in such a way that the woods could return, that nature could reabsorb the crazy cementitious cravings that have not created anything beautiful and that have not brought any income. A nation with a string of mountains spanning its entire length should keep this geography in mind. I believe that the time has come to consider the Apennines as the place where the strength of the past and that of the future combine. From Liguria to Calabria, now, it is a long story of landslides and depopulation, of old abandoned buildings and closed schools, of elongated, broken, deformed villages. It’s a story that doesn’t exist because it’s not news.»

Simone, how did this work come about?

Varco Appennino is the result of various contingencies: one year after the publication of Hotel Immagine [Donati’s first book, 2015, ed.] – which, being linked to the Italian news, was shot following the fast pace of events – I felt the need to rediscover a more calm and meditated way of photographing; I therefore chose to go back to medium format analogue photography to find slowness both in the shooting phase and in the rendition of the images. The occasion that prompted me to undertake this work was a trip to the inland areas of Calabria, during which I became aware of the richness of these territories and of how much there was to understand; I decided to explore them to deepen this intuition, photography for me is an opportunity for knowledge.

Why the Apennines? What made you interested in this topic?

In my longer works I have always chosen to focus on Italy, on the territory that I believe I can understand and tell in more depth. With the Apennines, in particular, I immediately perceived a sort of character affinity: these places resound deeply with my nature and the photographic style of the work further confirms this encounter.

Continuing along the path of research, the initial amazement was replaced by a slow realization of the sense of these territories, places where the relationship between people and landscape is extremely deep, almost visceral. I looked for faces and situations filled with stories that I decided, however, not to report in the book in order to leave room for images: I was not interested in a journalistic, analytical reading of the story; I preferred to let the atmosphere, environment and identity emerge. Working and discussing with Fiorenza [Fiorenza Pinna, curator and designer of the book, ed.] the project found its final identity.

Tell me about the collaboration with Fiorenza Pinna.

In the summer of 2019, when I had collected a good body of images, I asked Fiorenza to work together on the final stages of the work. We immediately found an excellent visual understanding on the direction of the project; the last images, the final pieces of the narrative, were born from our exchange of views. Her work was fundamental in giving more strength to my creative intentions, in defining the centre of the project, as well as in finding the right distance to eliminate some images I was at first fond of, in order to achieve greater continuity of meaning. We immediately worked on a rather essential selection, the discussion and exchange made the process natural. The sequence of Varco Appennino is very fluid and has a simple design that leaves space for images and texts, moving through small, significant graphic choices.

How was the relationship with Franco Arminio born?

Diving deeper into the work of Franco Arminio on the “inland territories”, I realized that his research method was very similar to mine: wandering without a specific goal, talking to people, telling about places and their vibe. I met him several times in his town – Bisaccia, in Irpinia – where the “Casa della Paesologia” is located; looking at his work, Vocabolario Apenninico immediately appeared perfect to act as a counterpoint to the images. With Fiorenza we decided to insert his “definitions” within the book to create two parallel paths; it is not a question of “captions”, but of a second interpretation, a dialectic with images.

As Arminio recounts in his Vocabulary, the Apennines have long been a place of emigration. Can they represent, today, a new goal, a geographical and symbolic perspective for the future?

I hope this work can be of help to reflect on the meaning of places that were the first to suffer the consequences of the increasingly faster economic and social processes that characterize our time. However, without substantial public intervention, I do not believe that it is possible to reverse the phenomenon of depopulation: people abandon inland areas due to the lack of services and job opportunities. There have been some virtuous examples, as in the case of Riace, but they are the result of local initiatives. Instead, central interventions and a long-term strategy are needed to make these places truly attractive. The road to recovery is not a utopia, but it takes time and willpower.

Do you think your work can help moving in this direction?

I have never really believed in the idea that photography can “change the world”. I experience images as awareness and memory, I believe that the identity of a photographer clearly emerges from the very modality of his work; in my case, in the proposal of a slowdown, of a quiet and attentive approach, already visually poorly aligned with the speed of the contemporary images. I have no ambition to provide solutions; I think my job as a photographer is to observe and describe aspects of society that I consider interesting and that I feel I want to share, hoping that my sensitivity will become an opportunity for reflection for those who want to dwell on the stories I tell.

Varco Appennino is a window on the memory of places, a path – almost a meditation – into the depth of belonging and the interpenetration between identity and territory. Simone Donati’s photographic book, which was edited and designed by Fiorenza Pinna, is accompanied by texts by Franco Arminio.

The book

Simone Donati

Varco Appennino

Witty Books, 2021

All images: © Simone Donati/TerraProject

June, 3 2021