by Federico Busonero

_

July 2020: I read of the news of Paul Fusco’s death in The New York Times. I am saddened and in shock, unable to give order to my memories and collect my thoughts to say farewell to my friend who is no longer with us. Some time had to pass for mourning the loss before I could write a few words about him. I was aware that Paul was seriously ill; the last time I could speak with him on the phone was in 2016, when he let me know that he was not in a condition to leave the clinic where he was receiving medical treatment. His voice was far away: “I do not have enough strength to continue photographing”, he said, and we agreed it was not the time for me to go to visit him. After a while, it was difficult to reach him on the telephone. I respected his desire for silence, as if he had wished to quietly leave the world that he had travelled for so many years, a world which his profound gaze unveiled to us. Paul has left us, and I can only preserve the memory of the days I spent with him in Italy, and before that, in Seattle and New York.

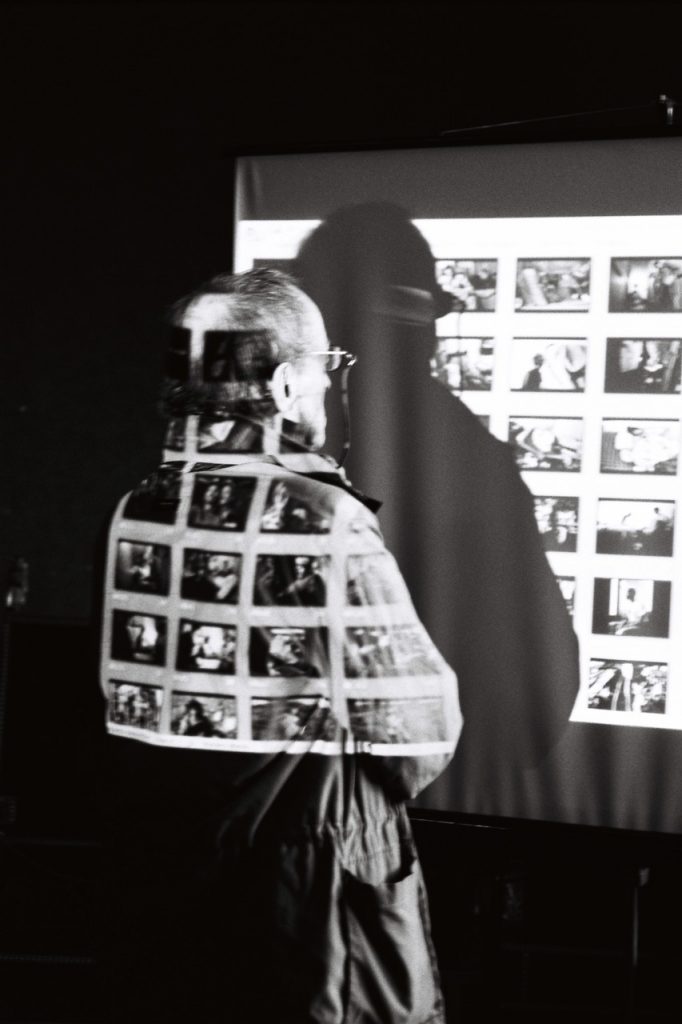

In August 2008, Paul had accepted with great enthusiasm my invitation to participate in a seminar on photography in Florence as guests of my dear friends, Stefano Vincieri and Federica Parretti, who had recently founded a cultural association, il Palmerino. Anne Sanciaud-Azanza, at that time curator of the Department of Contemporary Photography at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, joined us from Paris. Andrea Ulivi, editor of the publishing house Edizioni della Meridiana, joined as well, accompanied by some of his students. The atmosphere was convivial, and the days we spent together were very productive. Paul had an immediate rapport with the audience, and in particular with the students, who were eager to show their photographs to the “Maestro”, as they addressed him. I remember that, in observing their work, he said to them: “You have to ask yourself why you take a photograph. It does not matter what and how you photograph, what is important is that you know why you photograph something, rather than something else”.

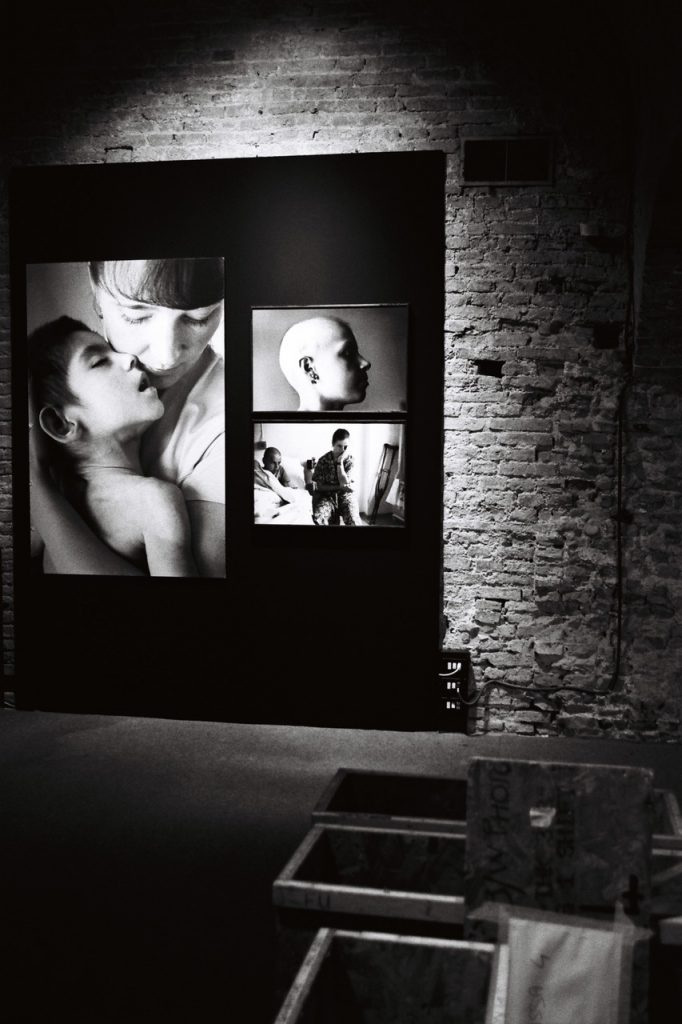

One year later, we met again at il Palmerino on the occasion of a retrospective dedicated to Paul which I had previously proposed to the Municipality of Siena. The exhibition, a partnership between the Municipality and Magnum Photos Paris, included Chernobyl Legacy – the photographs Paul made of deformed children in Minsk, the unspeakable aftermath of Chernobyl’s nuclear explosion – along with photographs from the RFK Funeral Train and Bitter Fruit series. Up to this day, in 2020, the photographs of Bitter Fruit, which dealt with the consequences of the Iraq war, have not been published. Perhaps they show an inconvenient truth, and America is not yet prepared to face the consequences of the war and bear the loss of those young lives.

Paul Fusco’s gaze is the gaze of one who has seen a great deal. The gaze of someone who has not only chosen to capture on film, in that instant, the suffering of others, but also to make the suffering his own. Within that image-document, invisible yet undoubtedly present, is the gaze of the photographer – his vision, what he is. We sense this, we feel it. His images penetrate us. They contain the memory of so many personal stories, each one different from the other, yet all of them resonating with the same helpless cry of pain. In each story of Bitter Fruit, as well as in all of the stories he has witnessed, Paul Fusco grasped and revealed the universality of human suffering. As we look at these images, we cannot avoid the physical presence of pain – we participate in it and we become aware of it.

The gaze of Paul Fusco is the stunned gaze of the deformed children we have guiltily forgotten in the orphanages in Minsk. It is the desperate gaze of the fathers, the mothers, the wives, and the children of the soldiers who died in Iraq for an unjust and senseless war. It is the astonished gaze of the Americans who see the end of their dream and hope in the passage of the train carrying Robert Kennedy’s coffin. It is the gaze of the victims of repression in Chiapas as well as in New York, and the hopeless gaze of California’s AIDS patients. The gaze of Paul Fusco – the quintessential photographer-witness – is the gaze of all individuals marginalized by history, oppressed and forgotten by an injustice which is deaf and indifferent. In his photographs, the protagonists are the non-protagonists.

Bitter Fruit can be interpreted as a testimonial of America’s uniqueness – its need to find a common identity when tragedy occurs. The symbol of this identity is the flag, which appears in almost every image: the official ceremony of the folded flag that the military presents to the families of the victims, the flag presented by Vietnam veterans to a widow as a final homage, the flag opened by a boy and a woman in the cemetery under a sky grey with snow, and the flags waved by children as their father’s coffin goes by. The flag is a presence, a memory, a souvenir, a comfort, a catharsis. The protagonists of Bitter Fruit gather around the flag in a state of despair, yet they maintain a composure as if to reassure themselves that the loss can be understood and justified in the name of a greater cause.

When I asked Paul how he was able to find the strength to carry on with his project, he replied that he had no other choice: “I need to show what they have done, what they have done to us here, as I have shown what they did in Chernobyl and everywhere else”. In these words exists the profound meaning of all of Paul Fusco’s work: in showing us what they did here in the U.S. – the resulting tragedy of another war – he took on the solitude of the people from whom hope had been taken away. The painful images of the funerals of Bitter Fruit join those of RFK Funeral Train made in 1968 when, in Paul’s words, “hope-on- the-rise had again been shattered and those in most need of hope crowded the tracks of Bobby’s last train, stunned into disbelief, and watched that hope trapped in a coffin pass and disappear from their lives”. Again, in Bitter Fruit, hope is crushed by a violent act and denied “to those who need it most”.

We must be grateful to Paul Fusco for his determination to put us in front of what was done to cause suffering to all victims of injustice and wars, universally and across borders. It can be debated today whether we are oversaturated by images of photojournalism which have become excessive, but we cannot deny that Paul Fusco’s images are different and constitute a powerful and tragic document, more necessary than ever in the digital age.

“Because there is the suspicion that photographs do not always tell the truth, the role of the concerned photographer and the independent sceptical photojournalist is more important than ever. Bearing witness is a difficult, and these days, often a thankless task, but there is only one alternative”. *

Paul Fusco’s photographs are a memento mori, a reminder of what we are and what we should not be. The photographer wants to be, with extraordinary effectiveness, a witness of his time, in the best tradition of “Concerned Photography”, so that what happened is not forgotten and condemned to oblivion. In this, his images are deeply personal, but not sentimental or moralistic. They are authentic.

* Martin Parr and Gerry Badger, The Photobook: A History, Volume II, p. 241. Phaidon, London, 2006.

December 28, 2020