by Liliana Grueff

_

In presenting his latest film Molecole (Molecules) at the 77th Venice International Film Festival, Andrea Segre spoke about the hollow spaces of Venice, where he shot the film during the lockdown, and also about the empty halls where it was about to be screened, only partially filled due to the distancing imposed by the pandemic. A correspondence extemporaneously highlighted by the director, that introduces and joins those explored in the film and to which he seems to rely in his painful and bewildered wondering about his relationship with his late father and with his city.

Surprised by the worsening of the pandemic in Venice, where he intended to shoot a film about high tide and excessive tourism, Andrea Segre decided to stay there and the film he was about to make took a completely different turn. Through the theme of emptiness and absence, the director declines the emotional core of his film: the unspoken relationship, interwoven with silences, between his father and with his city, also fragile, like his heart, suffering from a condition that will cause his death (and that perhaps, like his father, hides a secret from him).

Venice – city of the eye according to Josif Brodzkij – as it presented itself in that period, with its voids, its silence and its mirroring water, is the reagent that brings out latent thoughts and truths, and the “correlative object” of his relationship with his father. A difficult and courageous project, an intimate research born out of unforeseen and uncontrollable events, and which moves on the thin edge between an emotional experience and an investigation on a complex place such as the lagoon city.

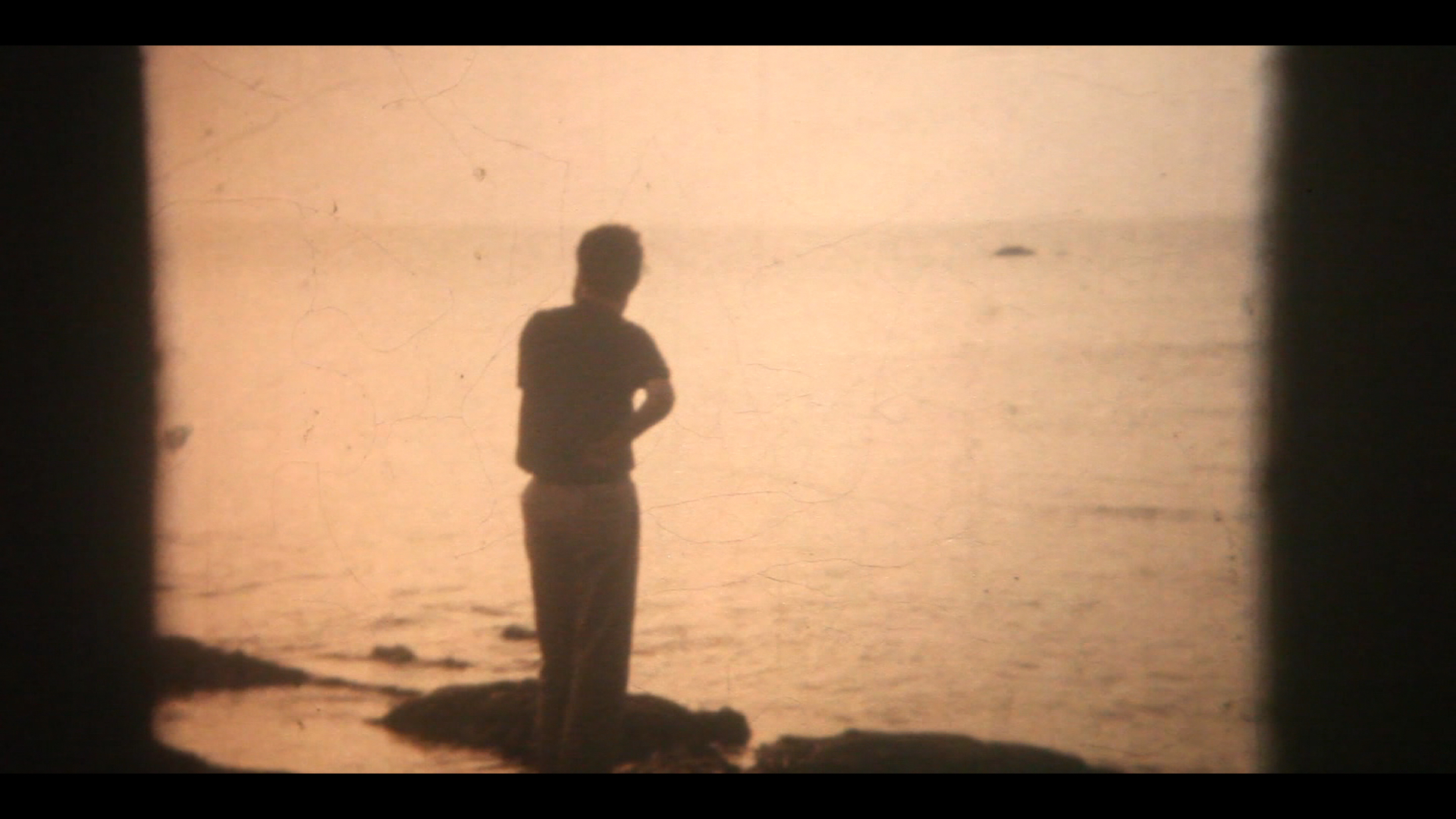

In his questioning as an adult son, the director retraces his relationship with his father and with the city, alternating family memories and documentary footage that show us a Venice that is not only a monumental city but also a lagoon city, made of islands, fishermen, sandbanks and resilient residents. And he gives us a film which is a cross between an intimate diary and a documentary, intense and engaging, with a subtle charm even if with sometimes uneven results.

Woven with familiar and archival footage as well as images shot by the author around the city and the lagoon, the film aims at going under the skin of the city and at the same time be an elaboration of the trauma of loss and disappearance. Loss and disappearance that Venice also experiences, representing almost a physical rendition of the voids and silences that characterized the relationship with the director’s father, and that the city, as well as the screening room, reverberates.

Certainly an impromptu annotation, that of the director on the screening room, but which shows a different attitude from the mostly documentary film narration of his most famous movies. If in a film the focus is above all on the narrative that unravels within the edges and within the sequence of images that constitute it, the correspondences, of places and circumstances, the coming out of the margins in a sort of spatialized mise-en-abîme, shows a sensitivity to the image close to photography. Photography as an introspective practice, as self-knowledge through the places that led the director to investigate both his father and the city.

Fragile clue, perhaps, but sufficient to alert the eye and attention to the “photographic” element. And in fact, the film is rich in photographs: photos taken by the director in Venice after the exceptional high tide of November 2019 – which show Venice in detail, of which the author emphasizes the ghostly appearance, almost a dis-appearance, as well as long lost footage shot by his father (almost to trace a genealogy) and family photos.

One especially is recurrent: one where the child author is in the arms of his father who is taking a photo in front of a mirror with his face entirely covered by the camera, and then, in a subsequent shot, revealed. Who is watching us? the director wonders repeatedly, and this is a question, albeit declined on an emotional and existential level, also exquisitely (and perhaps unconsciously) “photographic”: how not to think about “I’m looking at the eyes that have seen the emperor” with which Roland Barthes begins his masterful reflection on photography?

On the sidelines of a recent Florentine screening of his film, the director, connected via phone, when asked what his relationship with photography was, replied that, until the discovery, a few years before, of an old Olympus belonging to his father, he wasn’t particularly attracted to it. Since then, he has started taking pictures, shooting a few films a year, and is fascinated by the limitation constituted by the small number of shots that the film allows, and by the time that elapses between shooting and viewing the photo, which allows him to think and to reflect.

What Andrea Segre said did not surprise us, and confirms the intuition of a sensitivity close to photography. An echo of which seems to be present in this latest movie, which could also be seen as a tension between pose and passage, between the silence of the images, their not being able to give answers to the questions that the narrator’s voice asks, and the desire to bring them, through the cinema, onto the slippery ground of meanings and correspondences.

However, from a photographic point of view, we do not find in the shots of the city the expressive effectiveness of the familiar images and the photographs taken by the director in the aftermath of high tide.

It is in the final part of the film that the images of Venice reach the intensity of the director’s painful meditation, and express the theme of his reflection, which is death (or life).

When the camera takes us to a livid, nocturnal, foggy Venice, where the lagoon is amniotic fluid and also Stygian swamp (and a photograph of Venice by Gianni Berengo Gardin, L’angelo della morte, springs to mind) and where the calli are narrow, forced passways and threshold towards the unknown.

It is here that – to use Roland Barthes’ words again – the images “happen to us”. Like Venice must have “happened” to the director.

All images come from the film Molecole. Photography by Matteo Calore and Andrea Segre

November 10, 2020