by Daniela Tartaglia

_

For me, the idea and image of the city has never been purely landscape,

but more its whole and its community. It has always been civitas more than urbs.

And it can very well be called the Augustinian image.

(Mario Luzi)

It is the Italian and European city that the great poet has in mind when he outlines the characteristics of his ideal city, a city with a strong identity, not yet the “distant”, alienating, subject to insignificance space to cross continuously, without break or end, as most American and Chinese megalopolises to which the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy has dedicated his recent reflections.

The image of the city is impervious – Luzi writes again – because it no longer contains our illusions.

Modernity, obsessed with future and progress, has in fact considered cities and houses only as a mechanical cluster of materials and shapes, functional to an idea of living that has nothing to do with the ancient idea of nurturing and preserving, giving up a past and a memory capable of orienting the present and giving urban development a temporal depth.

It is the same bitter reflection that Renzo Piano made in his book/interview: “Our century has corrupted the city, the great invention of man, has polluted its positive values, altered the mixture of functions and its own sociality as well as the quality of the buildings, pursuing limitless growth that has blown up our cities and (…) built the worst suburbs, made of walls but without the structures in which a society organizes itself and lives.”

Today, as the health emergency has made the limits of globalization and of living in the big megacities stand out with arrogance, we must have the courage to reverse the course, to challenge Utopia to become a possible place, giving back to living its ancient function.

It is not a question, however, as Renzo Piano states, “of putting on slippers to walk in a meadow but of practicing sustainable architecture, understanding nature, respecting fauna and flora. Place buildings and systems correctly, make good use of light and wind. The city is in fact much more than a collection of buildings, institutions, streets or squares (…). The city is an attitude, a state of mind, an atmosphere of the spirit, a sensation. The city is emotion.”

It is basically a question of changing sensitivity and approach, to activate architecture and sustainable development, the result of a process of ethical rethinking on the meaning of living, on the power of architecture to inspire different ways of being together, to build social relationships, interconnections.

Within this complex scenario, what has been and what continues to be the role of photography in the transformation of architectural culture? What are the photographers who have distanced themselves from a substantially traditionalist attitude towards the use of photography, found on the pages of architectural magazines? Magazines that considered – and, in most cases, still consider – photography only in close relationship with the designer’s drawings, limiting themselves to didactic images, rarely able to observe what the project did not foresee.

Certainly among the protagonists of a wide-ranging cultural change, we find that handful of names that Morpurgo, already in 1979, defined as “curious travelers”: Mario Cresci, Luigi Ghirri, Guido Guidi, Mimmo Jodice, Gabriele Basilico, Giovanni Chiaramonte.

Gaddo Morpurgo wrote about them in the pages of the Rassegna/Rivista di Architettura: “Once all dependence on the image of the project is abandoned, photography offers us different images of that same architecture that we had considered completed at the time of its realization. The photographer returns to the place of the architectural event following his own itinerary and, by selecting and juxtaposing partial images, he constructs another context in which to review the characteristics of a space, the effects of a project. (…) In these photographs, we find that image of the stratification of time and use that has substantially changed the image described by the project. (…) The photographer appears more and more like a curious traveller who searches, selects and above all compares the images he finds along his physical and cultural journey. Much more than a peaceful witness.”

Among the photographers who have worked for a long time on the stratification of time and the fate of western cities, the figure of Giovanni Chiaramonte has emerged since the Seventies. Born in Varese but strongly linked to Sicily, his homeland, a wide-ranging photographer and intellectual, Giovanni Chiaramonte was also the creator and director of book series, founder, together with Luigi Ghirri, of the Punto e Virgola publishing house, professor of photography and history of photography. Appreciated by the main architecture magazines and by the major architects of his time for his ability to stage the chaotic order of the suburbs and large cities, Chiaramonte has photographed European cities for a long time but, in his reading of space, has always sought to put man and his living in the world at the centre.

Going deep into the movement of life – said Chiaramonte in a recent conference at the faculty of architecture of the University of Palermo – is one of my main objectives. For this reason, when I photograph the city, the place of living par excellence, I cannot forget about man. Moreover, experience tells me that human events take place, unexpectedly and unpredictably, in a scene of the deep, great world and that, when a man looks at the world, not only through his eyes but through the lens of a camera, through a screen – which is always a geometric, Euclidean figure – that world immediately becomes the “scene” of an event in which not only the photographer, the one who is watching, but also the world and its inhabitants are personally involved.

In cities such as Hamburg, Berlin, Amsterdam, Giovanni Chiaramonte has intensified the experience and perceived a way of experiencing contemporary cities completely different from what experienced in the Chinese or American megacities.

Despite being, like all contemporary cities, subject to continuous evolution, to an incessant transformation, a sort of construction site in progress, where something is dying and something else is born, the cities of northern Europe – states the photographer – are distinguished by the ability to combine technological progress and environmental protection, for having adopted, as a unit of measurement, the well-being of man, his ability to live “a freed time” and to enjoy both surface and underground spaces in full harmony. In cities such as Hamburg or Amsterdam, there are areas that favour long walks and the contemplative dimension, leaving behind traffic, consumerism. There are houses, even modern ones, which are not out of scale architecture, which do not impose themselves with violence.

“These are the cities that” – as Renzo Piano says about Berlin –” have developed the richness and complexity of the functions of the city, its intensity and therefore its human dimension. The fact is that on the same ground, on the same square there are people who live there, people who come for entertainment, to go the theatre or the cinema, to shop, visit, tourists in a hotel and people who come to work. A mixture of all these functions in the same place: this makes the city. (…) The city must express joy (..). Who said that a city to be true, authentic must be gloomy? A city must be intense, not gray, or heavy.”

Just think of Potsdamer Platz, a delusional elucubrated fantasy – as Vargas Llosa defines it – of a city in constant transformation such as Berlin, a city that Giovanni Chiaramonte has photographed since 1983, when he was invited for the first time by Lotus to photograph the architectures of Alvaro Siza and Oswald M. Ungers.

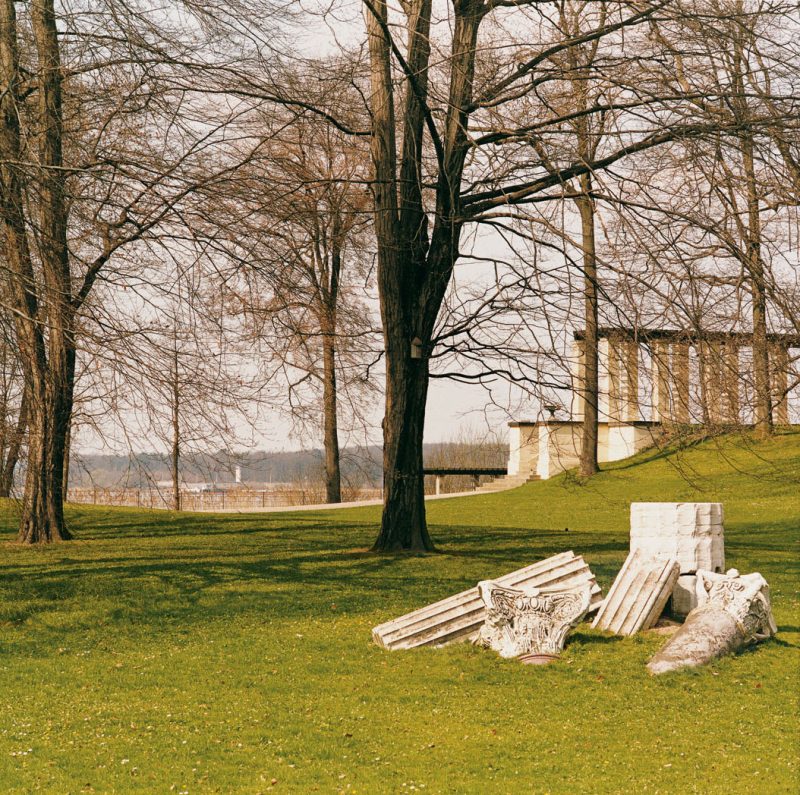

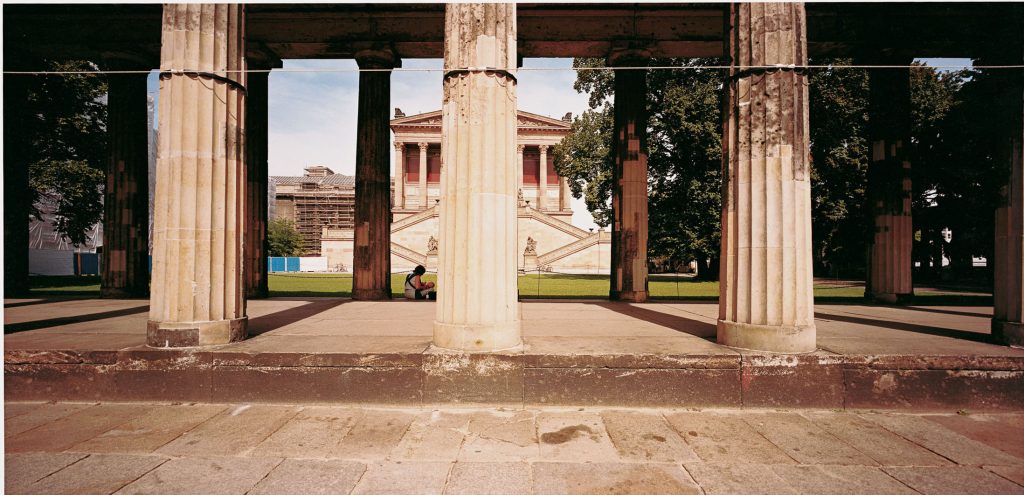

Since then, Chiaramonte has dedicated many years of his photographic travels to Berlin, to investigate the transformation but also the history of the German city, from its foundation in the neoclassical steps of ancient Greece and Rome, to the ruins left by the Second World War and the reconstruction occurred after the fall of the wall.

The images, immersed in a broad context that tries to embrace all the other buildings and, where the idea of an open city is perceived, open on the sides and towards the sky, are almost all made in medium format with a camera without decentralization and with a maniacal preference for the square or double square to which Giovanni Chiaramonte attributes a symbolic value.

The photographer seeks a tactile, intimate knowledge of space and matter, tries to produce images that are capable of emotion, configuring his poetics in that personal and coherent way that led him to collaborate with the major architects of the second half of the twentieth century. It’s overbearing the closeness to Andrej Tarkovskij’s cinematography, a poetic attitude that is not only a figure of speech but a perception of the world.

In my images I often tell the solitude of cities, but it is a solitude that opens up to infinity. In some ways, it is an invitation to seek man and find him even in those suburbs that seem forgotten, also because God never forgets humanity.

All images: © Giovanni Chiaramonte

July 9, 2020