by Daniela Tartaglia

_

I finished my visit to the Lucca Center of Contemporary Art, which hosts the great Classics retrospective dedicated to Werner Bischof (1916-1954), with a smile on my face, both for the quality of the cultural proposal and for having seen an entire class of primary school children visiting the exhibition. It was a pleasure to imagine the astonishment of those kids in seeing the rigor, love, and emotional participation that emerges from the shots of the Swiss photographer and to think that perhaps this experience will leave a lasting trace in their imagination, educating them to a thoughtful and not sensationalistic approach to photography.

Through the 105 photographs of the exhibition, the visitor can enter not only the universe of one of the great reportage photographers of the twentieth century but also the history and the vocation of Magnum, the prestigious photojournalism agency founded in 1947 by Cartier-Bresson, Capa, Seymour and Rodger to ensure the material and moral independence of its members, protecting them from the censorship of publishers and art directors. Through the reflections of the photographer in the exhibition, the visitor has the opportunity to examine the themes dear to the author and that, even today, should make us think about the role of reportage photography.

Bischof did not consider himself a reporter and never liked this definition; he did not want to be limited to producing timely and effective documentation and he was always polemic towards war correspondents, “the battlefield hyenas who see only what could impress the international press, forgetting that there are human souls even without a uniform”. Perfect example of this is a photo, exhibited in one of the eight sections in which the exhibition is divided, which condemns this rapacious attitude of fellow photographers, depicted piled on one another as they try to get their scoop. A man of great morality, in his brief life Bischof has always confronted himself with doubt and with theoretical reflection: he asked himself in what relation reality and formal beauty were, how much the fast documentation of events was to be chosen over understanding and interpretation, whether it was more important to represent the story in its events or to enter the narrative in the long term.

In the biography of an author there often lay the answers to key questions and in fact his diaries and his letters to his mother tell us of a constant tension aimed at resolving dialectically the contrast between art and reality, between beauty and tragedy, of the will to reach a form of expression capable of mediating ideological commitment with the rigor of formal composition.

The influence of his mother, passionate about religion and philosophy, was decisive, but the experience at the School of Arts and Crafts in Zurich where he met his teacher Hans Finsler, leading exponent along with Albert Renger-Patzsch and Karl Blossfeldt of the New Objectivity movement, remains essential for his education. A great lover of painting, discovered in his childhood, and in deep harmony with nature, Bischof was educated by Finsler to the passion for natural geometries and the beauty of objects, elements that the New Objectivity movement placed at the centre of its interest. In photography, this meant breaking with pictorialism, with complicated charcoal and bi-chromate gum prints, with the use of soft focus and claims, instead, the centrality of direct vision, of the matter-form-function of objects.

This approach influenced the style of young Bischof who, in his Zurich years, experimented with curiosity and freedom the possibilities offered by the photographic medium, always trying to find order and not randomness in things.

The research on the material structure and the study of light variations could not entirely satisfy a complex personality such as that of young Werner, a photographer in search of his own humanity. Deeply struck by the events of the Second World War, Bischof began to wonder about the meaning that art and beauty can have in a world torn by suffering. From 1945 he began to transfer the attention once reserved to forms, onto man, to his history and to his vulnerability. The “face of the suffering man” soon became the central nucleus of his work and photography Son of Italian refugees, taken in a Ticino refugee centre, can be considered the key image of this new path.

Bischof undoubtedly suffered from the need, common to all European photographers of the immediate post-war period, to forget the horrors of war, and turned to lyrical images in which women, children and fragments of the everyday life were the privileged subjects. Unlike others, he managed to stay away from sentimentality and to maintain strong adherence to reality.

The young Werner participated in the theoretical debate on the alleged objectivity of the photographic medium and knew well that photography can make reality tolerable, just as beauty can become a lie: nevertheless he never gave up showing, through images, his trust in the world and man. The ability to become an interpreter of the great historical-social changes was in fact flanked by a humanist kind of photography that, rather than documenting, preferred to interpret things, to accentuate intuitions or atmospheres.

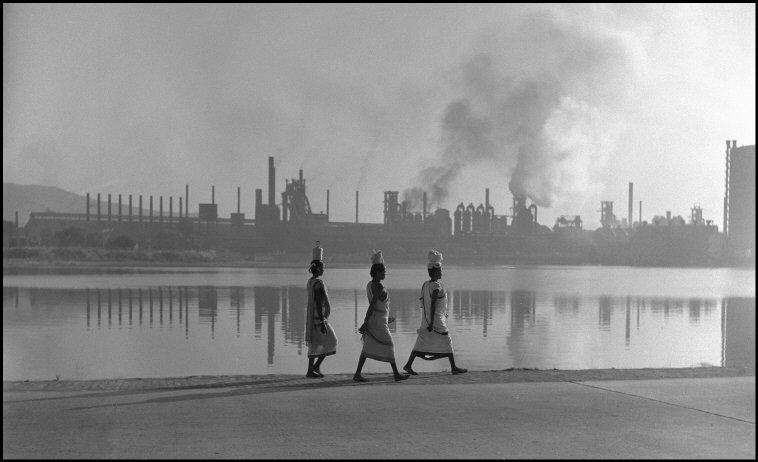

In front of the evil of the world, Bischof tried to never neglect the harmony between men and things, convinced that beauty is the very truth of nature and not an arbitrary aesthetic embellishment. It is this dream of purity, this unshakable ideal of a better world, the key to approach his photographic production. Supported by the strength of pity, Bischof in fact reached to produce strong images although sculpted with extreme measure, because supported by the rigor of the formal composition. In his work, tragic events such as war, death and hunger never become pretexts for impact images: the tragedy remains in things and is never expressed with linguistic elements that emphasize their theatricality. Everything is structured under the banner of formal equilibrium: starting from the composition that draws from classical schemes and rarely experiments with the use of wings, casual framing, blurred or out of focus shots. Even the prints are sharp, in order to allow the reader a complete decipherability.

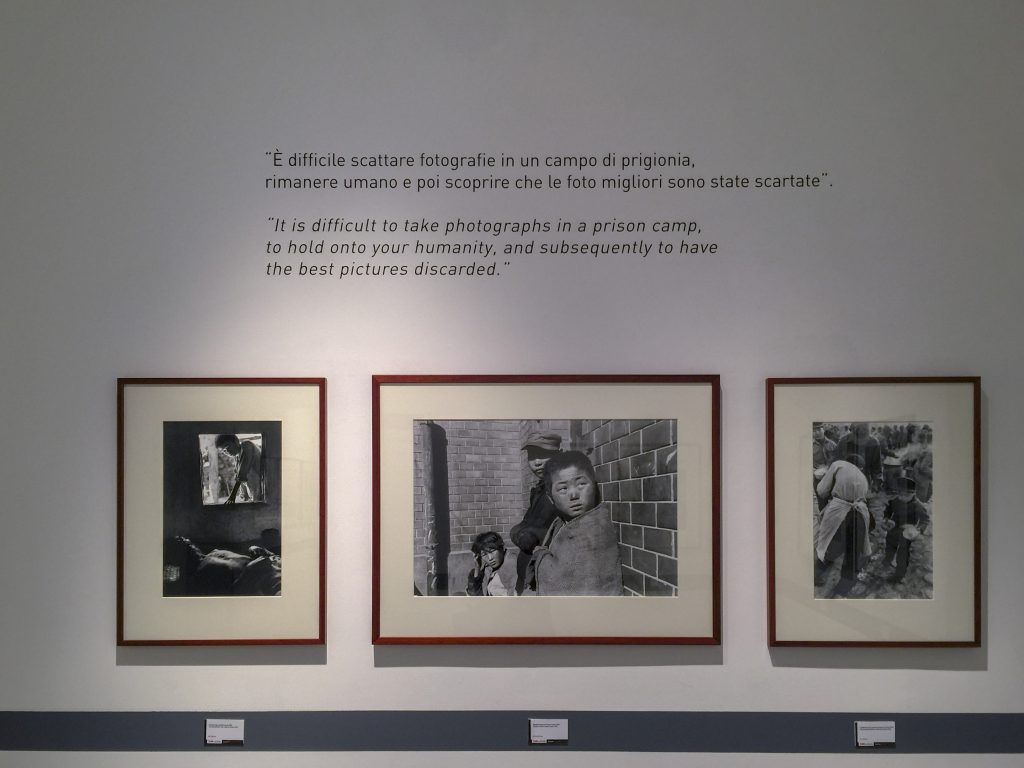

Joining Magnum in 1949 radicalizes this ideal and emotional tension and pushes him to follow his inner impulse even further, trying to talk about himself, to go into the photographic stories he faces without giving himself strict limits of time, convinced that “only a thorough, complete work, realized with a total commitment and involvement, can be of value”. Between the years 1950-1954 he realizes some of his most significant reportages: just think about the service on the famine in India, the one on the prison island of Koje-do in Korea or the splendid photographs taken in Hong Kong and Japan. As the images become more and more intense and notoriety grows, it is increasingly difficult for Bischof to manage emotionally the relationship with the press and the desiderata of the great newspapers: the photographer feels that “the hunt for the Story has become difficult to keep – not physically, but mentally”.

Discouraged, he writes: “Now the work here no longer gives me the joy of discovery; here what matters more than anything is material value, making money, creating stories to make things interesting. I hate this kind of trade of feelings … It was like prostitution, but now I had enough”.

Unfortunately, this awareness and the need to look beyond will be tragically cut short by the car accident in which Bischof lost his life, 4000 meters above sea level, in the Cordillera of the Andes.

His writings and photographs witness the value of a high-level human and professional experience.

Images in which the heartfelt participation takes the place of action, of visual shock or of the simple description of the event, forcing us to reflect on the role of photojournalism and on the social and cultural responsibility of the photographer. Today more than ever it is necessary to wonder if it makes sense – for the so-called “street photography” – to continue to challenge the laws of possible, new and surprising, producing images that are increasingly sensational and of immediate consumption. It is an open, difficult question, but one that needs to be asked again.

This exhibition suggests that perhaps, as Roland Barthes wrote, photography becomes subversive “not when it scares, upsets or even just stigmatizes, but when it is thought provoking”.

WERNER BISCHOF | CLASSICS

curated by Maurizio Vanni e Alessandro Luigi Perna

Lu.C.C.A. – Lucca Center of Contemporary Art, Lucca

Via della Fratta, 36, Lucca

7 September – 7 January 2020

Tue-Sun: 10AM- 7PM

November 24, 2019