by Daniela Tartaglia

_

Time is a state.

It is the flame

in which lives

the salamander of the soul of man.

Time and memory are merged into each other,

they are the two sides of the same coin.

(Andrei Tarkovsky)

Resurrecting the huge palace of memory – wrote Marcel Proust in one of the volumes of the Recherche, a literary journey on the theme of memory. Exactly what the great Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky (1932-1986) managed to do in cinema, being a passionate reader of Proust, as well as Dostoevsky. Author of milestones in the history of cinema such as Ivan’s Childhood (1962), Andrej Rublev (1966), Solaris (1972), Mirror (1975), Stalker (1979), Nostalghia (1983), The Sacrifice (1986), Tarkovsky is characterized by a very personal look at the world, a look that brings his films closer to poetry and prayer than to the solid organizational and professional structure to which the world of cinema usually refers.

Growing up in the shadow of the visual suggestions of the great Russian director, I too felt the need for his films, like the factory worker from Novosibirsk who wrote to the director: “In a week I went to see Your film four times. And I went there not only to see it, but also to live a few hours of a real life, together with real artists and real human beings… All that torments me, that I miss, that I long for, that outrages me, that makes me sick, that suffocates me, that enlightens and warms me, that I live by and that kills me, all of that I saw in Your film, as in a mirror. For the first time a film has become reality for me, that’s why I go see it: I go to live in it.”

Filmic image and photographic image in Andrei Tarkovsky’s vision both arise from a poetic urgency, which is not a simple literary genre but a perception, a philosophy, a special relationship with reality. The poetic attitude, in the vision of the great Russian director, however, is not vagueness, dream, special effects, it does not act as a generator of Mannerist symbols and allegories, it is not far from the factual concreteness of real life. Conversely, it is – to use the words of the poet Yves Bonnefoy – “suspended and enchanted resistance to nothingness, proximity to things, to their breath, to free them from their reduction to the letter, to the pure signifier.”

In Tarkovskian cinematography, the main formative principle has always been the observation of life in its pure state. Observation, accuracy and precision which, however, needed to be contained, sculpted and dilated over time, which required a great moral and spirituality like the one that guided the man and the artist throughout his life.

Andrei Tarkovsky writes in his Sculpting in time, a famous text of film analysis and his visual testament: “The image is not a certain meaning expressed by the director, but a whole world that is reflected in a drop of water, in a drop of water only […] the artistic image is a seed, a living organism in evolution […] The artistic image is in itself an expression of hope, a cry of faith, and this is true regardless of what it expresses, even if it is the perdition of man. The creative act is in itself a denial of death. Therefore it is inherently optimistic, even if the artist is ultimately a tragic figure.”

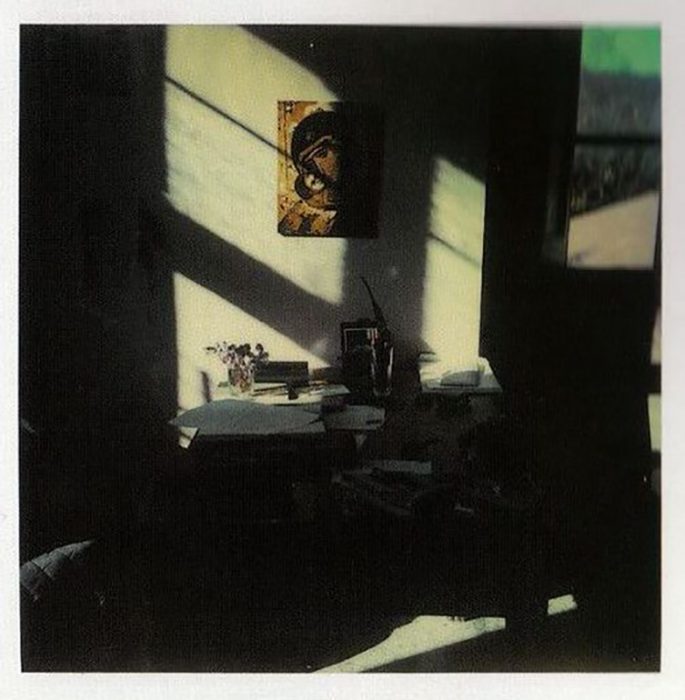

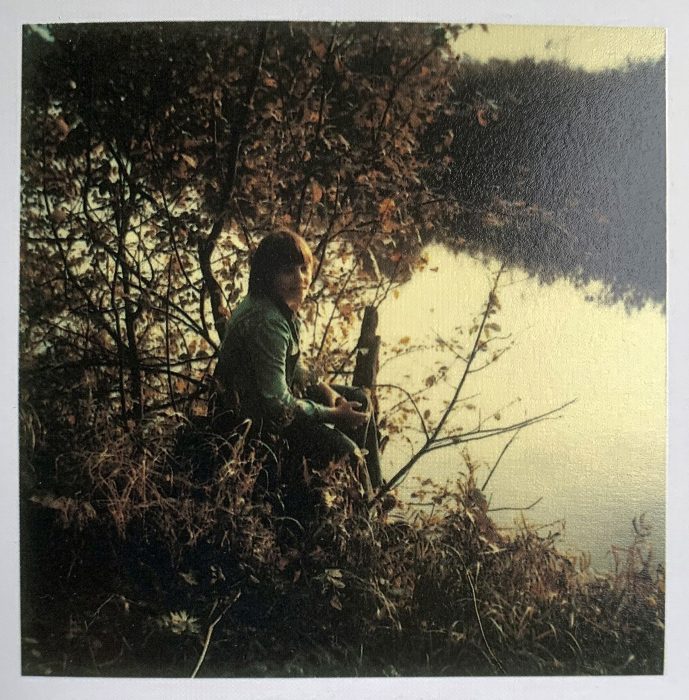

Even in the instant photography that Andrei Tarkovsky began to use in 1977, this strong spiritual inspiration and this incessant reflection on time passing by are evident. In a particular moment in the life of the great Russian intellectual and director, characterized by deep conflicts with the leaders of the Soviet Communist Party that will soon lead him on the road to exile – Italy, then Sweden, finally Paris where he died and where he is buried – his Polaroid becomes an irreplaceable travel companion, a visual notebook, a tool to freeze a fragment of reality, to stop time and project it into an infinite and absolute space. Unlike other photographers who have used Polaroid as a toy, a tool for recording the chaos of life, an expansion of spatiality, the Russian director uses instantaneous photography to take possession of time and memory, to resurrect memory. In accordance with his aspiration to establish a very close relationship with life and with the passing of time, he uses a simple photographic technique, which does not need subsequent redefinitions of the image in the darkroom.

His are quick glances, “flights of butterflies around the eyes of those who feel the brevity of life, bread to eat together with others” – as Tonino Guerra, his friend and screenwriter, as well as the person behind Tarkovsky’s encounter with the Polaroid SX 70, wrote. A camera used for a long time afterwards to investigate and memorize the possible settings for the film Nostalghia.

Andrei Andreevic Tarkovsky – son of the director and president of the International Institute that bears his father’s name, based in Florence, in via San Niccolò – tells us about his father’s intense relationship with the immediacy of Polaroid:

I don’t remember him having any interest in analogue photography, I’ve never heard him talk about photography or established authors. He did not buy photography books although some photography catalogues can be found in his library. He was interested in paintings of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, from which he drew great inspiration, and in music. But he liked Polaroid a lot for its immediacy, for the possibility of seeing the result immediately. Also, he ended up mastering it very well and was able to control the frame and the parallax defect. When he returned to Russia after 1980, he brought the Polaroid 600 with him and took many pictures, perhaps his most beautiful and intense. I don’t know if he foresaw then that he would never return to his homeland. Surely he had the intuition, given the great sensitivity he was gifted with.

Furthermore, some beautiful Polaroids taken in Russia, in 1981, in our country house, located 300 km from Moscow, were used to help his memory in reconstructing the scenography for the family home, during the making of the film “Nostalghia”. When my father arrived in Otricoli, an Umbrian town on the banks of the Tiber where some scenes of the film were to be shot, he explored the place and, based on those images, chose exactly the frame of the shooting. He placed a stake in the middle of a field to remind himself of where the camera would later be placed and where our country house in Russia would have to be rebuilt. The assistant of his set designer told me that when my father returned a few months later, he noticed that the reconstruction of the facade of his house in Myasnoe did not coincide with the chosen angle. He remembered well the ratio and the size of the house – he had, among other things, left the polaroids to the set designer to work by them – and so, instead of shifting the point of view of the shot, as perhaps anyone else would have done, he moved the house two meters to the right, forcing the set designers to dismantle and redo everything. It was very accurate. Very attentive to details and the sacredness of memory.

Although there was no awareness, on the part of the great director, of an authorial vocation in photographic practice, his polaroids testify to its emotional and spiritual coherence, centred on the practice of memory as creation, on the pietas, through which Tarkovsky tried to exercise his creative freedom. Convinced that the movement of the heart, triggered by memory, was the only one capable of allowing the eyes to see beyond the boundary of appearance.

His artistic research – both in cinema and photography – was therefore fundamentally structured on the sacredness of vision, on the perception of the depth of time in which observation and contemplation can merge. Not many directors and photographers have been able to pursue this practice and give shape to this perceptive mechanism in the construction of shots and sequence shots, a mechanism that has more to do with Zen practices or self-awareness than with a solid and reassuring professional and organizational skill. In his book Sculpting in time there are many pages dedicated to the intrinsic difference between profession, trade and art within the practice of cinema, many examples through which he tries to clarify that “the most difficult thing for a person who works in the field of art is to create one’s own conception, without being afraid of its limits, not even the most painful ones, and to stick to them. The simplest thing, however, is to be eclectic, to follow the stereotyped forms and models of which there is no shortage in our professional arsenal. This is easier for the artist and simpler for the viewer. But therein lies the most frightening of the dangers: that of getting lost.”

In all the hundreds of Polaroids that he loved to shoot to immortalize the misty, intimate and familiar landscapes of his country house in Russia as well as in the series taken during the making of the film Nostalghia in Bagno Vignoni, Monterano, Civitavecchia, the gaze of Tarkovsky caresses things and people, imposing a sacral attitude, a sort of genuflection towards emotions and memories evoked by those saturated, pastel-colored images.

His passion for paintings is evident, his closeness to the Flemish landscapes of Bosch and Bruegel, to the paintings of Antonello da Messina and Piero della Francesca, to the inverse perspective of Russian icons, but basically Tarkovsky’s gaze is aimed at investigating everyday life to produce an image that is closer to the psychological truth than to the factual one. Even the chromatic choice – chosen expressively through the use of Polaroid and a certain light – reveals a considerable awareness and distrust of the too active effect of colour, of its mechanically exact reproduction that is neutralized by Tarkovsky in favor of the amazement that arises from the observation of natural elements, from the flowing of water – an element very present in his cinematography – from sun rays shining through the leaves, from the sound of rain and wind and also from the inside of the home, the garden, the faces of loved ones, with a neverending longing for his homeland, his mother Russia, for his home, for his son Andrei and for his dog Dak, who were held hostage by the Soviet government during his exile.

Even his son Andrei Andreevic, author of a beautiful documentary on the biographical and artistic story of his father Cinema as prayer (2019), confirms the unresolved relationship that Tarkovsky had with colour, even in film production:

He did not like colour very much. In his films there is never a full colour, except in “Solaris”, based instead on chromaticity, on the strength of colour, obtained also through a great work of post-production. Usually, he loved black/white or a very faded colour, very similar to that of the Polaroids produced in those years and due to a chemical peculiarity of the film. The homogeneity found in his images and films depended a lot on the atmospheres, the surrounding environment, the light he sought for and received inspiration from, not so much on the colour correction made in post-production. He had a special flair for places, for certain atmospheres capable of expressing emotional tension. He looked for them and when he found the place, for him a true source of inspiration, most work was done.

Most of these polaroids, taken between 1980 and 1984, were found, after the death of the director, in a shoe box, they were selected and then collected in the volume Luce Istantanea edited by Giovanni Chiaramonte and Andrei A. Tarkovsky, with an introduction by Tonino Guerra (Della Meridiana Editions, Florence 2002). In this book, we found it interesting the balance that the two curators managed to achieve between texts and images, the dialogue that is established between the images of the book and the reflections (or simple observations) of the director, taken from his personal diaries (Martyrology) and from the essay Sculpting in time. Written in a simple and direct style, these reflections have the merit of introducing us, immediately, into the complex and tormented artistic and spiritual story of Tarkovsky, into his mysticism, into the theme of roots, of the bond with the family home, with childhood, with his homeland, with the land, with the haiku – the Japanese poetry to which the great director felt very close for the simplicity and precision of the observation.

He wrote in this regard: “The haiku cultivates its images in such a way that they mean nothing, outside of themselves, yet at the same time expressing so much that it is impossible to grasp their overall meaning.[…] Whoever reads haiku poetry must dissolve in it as one dissolves in nature, sink into it, get lost in its depths as in the cosmos where neither low nor high exist. […] The Japanese poets were able to express their relationship with reality in three lines of observation. They did not just observe it, but without agitation and without restlessness they sought its eternal meaning. The more exact the observation, the more unique it is. And the more unique it is, the closer it is to the image.”

Accuracy of observation but also the ability to go beyond the contingent, in search of eternal meaning: a great issue that also involves the profound identity of photography and underlines its revelation value because photography – to put it in the words of Jean-Christophe Bailly – “carries in his grasp […] the revelation of a state of reality that the habitual gaze leaves dormant.”

The book:

Andrej Tarkovskij

Luce istantanea

edited by Giovanni Chiaramonte and Andrej A. Tarkovskij

introduction by Tonino Guerra

Edizioni della Meridiana Firenze, 2002

All images: © Archivio Andrej Tarkovskij, Firenze

November 10, 2020