by Daniela Tartaglia

_

Photographs pose questions concerning the land and the sea,

the outline of one and the other, the ways of presenting them, separately or together.

They combine the world and the outlook on it, space and the concept of space.

(Pedrag Matvejevic)

This wrote Pedrag Matvejevic in one of his famous essays on the Mediterranean, a text halfway between a pilot book and a logbook, a poetic dissertation and a historical text. And it is the Croatian intellectual and historian who was brought to my mind, right from the start, by the long conversation with Pietro Paolini and by his repeated stress on the importance of walking and “wandering” within his visual research.

But I also thought of Bernardo Secchi, of the importance that the great architect and teacher gave to mingling, to the need of entering the folds of a city, when he said that town planning is done with the feet, since the process of knowledge is a mechanism of continuous interrogation but also of randomness, listening and letting the flow of energy go through yourself. A sign that the desire for knowledge and regeneration of the mind, for exploring areas not yet covered by one’s feet, can represent an extremely profitable way of reaching not so much mere knowledge, but – as Henry David Thoreau claimed – intelligent harmony.

It is therefore with the buscar, the research, that my reflection and my investigation into the work of Pietro Paolini begins, on his latest book Buscando a Bolivar which, already in the title, contains a declaration of intent.

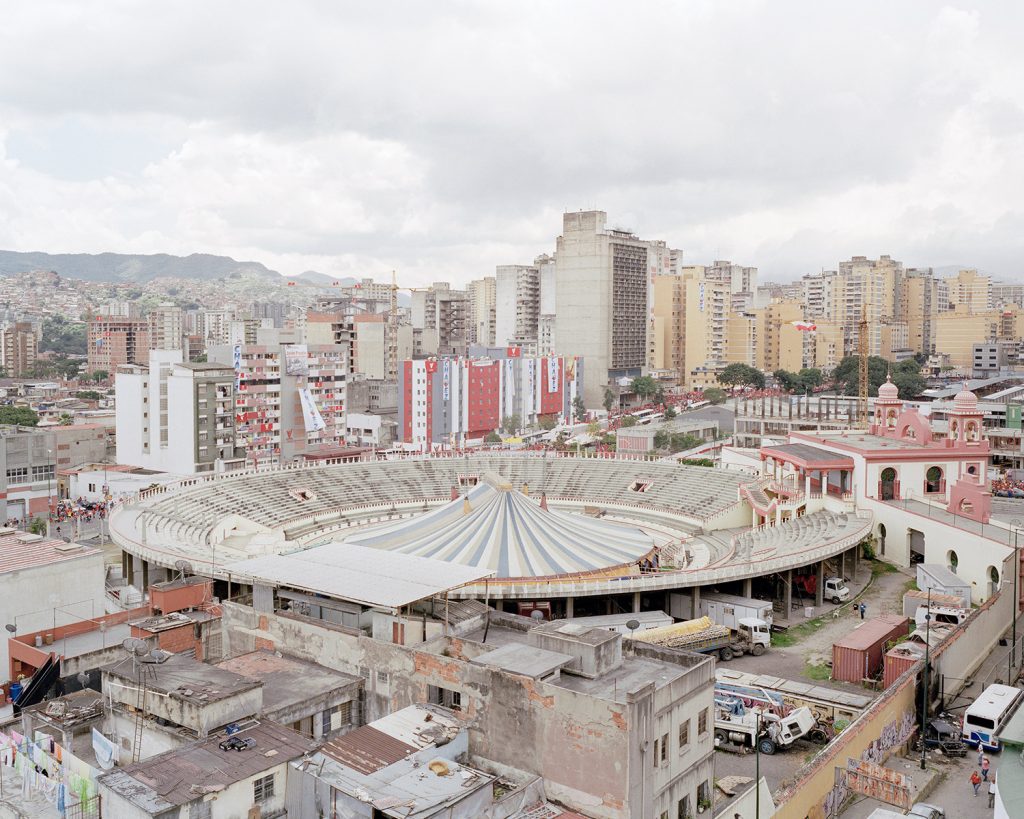

Like Simon Bolivar – legendary nineteenth-century Venezuelan revolutionary, whose great dream was to bind together in a federation of states all the South American colonies freed from Spanish domination – it seems to me that Pietro Paolini, in this book, managed to keep together the complexities and contradictions of the reality he represented, but also the richness and the continuous inquisitiveness of the gaze, in order to arrive at a sort of open evocation/narration.

We are faced with a rarefied and suspended project, in which contemporary vision and magical realism coexist and integrate admirably, making us glimpse the great hopes but also the great contradictions of the three South American states – Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador – that the photographer has travelled extensively from 2008 to 2014.

Attracted from a very young age by Latin America, thanks to his mother’s interest in music and literature, he made his first research trip to Venezuela in 2004, together with some friends interested, like him, in studying its historical/social side. It is the beginning of a passion, not yet over, which leads him to return to Caracas countless times and wonder about the political phenomenon of Chavismo and, subsequently, about the new Latin American socialism that sees in Chavez, Morales and Correa, at least in the early stages of their presidencies, the antagonists to neoliberal capitalism.

The project is therefore based on the hope that Pietro Paolini has breathed in the South American continent, on the collective enthusiasm for an opportunity of change and for a more egalitarian society, on interest in the strong political dynamism and on the force expressed by the indigenous social movement.

Although these popular aspirations were later denied and crushed by the actions of politicians, drowned in corruption and in the strong polarization taking place in South American society, they nevertheless represented a great challenge as they opened up to hope. And this strong desire for a new world, sensed by Paolini, leaves its trace in the book and in the significant extracts of the constitutional papers of the three countries that accompany the images.

EN TIEMPOS INMEMORIALES

SE ERIGIERON MONTAÑAS,

SE DESPLAZARON RÍOS, SE FORMARON

LAGOS.

POBLAMOS

ESTA SAGRADA MADRE TIERRA CON

ROSTROS DIFERENTES, Y COMPRENDIMOS

DESDE ENTONCES LA PLURALIDAD

VIGENTE DE TODAS LAS COSAS

Y NUESTRA DIVERSIDAD COMO

SERES Y CULTURAS.

NOSOTROS Y NOSOTRAS,

RECONOCIENDO NUESTRAS RAÍCES

MILENARIAS, DECIDIMOS CONSTRUIR

UNA NUEVA FORMA DE CONVIVENCIA

CIUDADANA, EN DIVERSIDAD Y

ARMONÍA CON LA NATURALEZA, PARA

ALCANZAR EL BUEN VIVIR.

The book is also the result of a rethinking with respect to the methods of documentary narration. Pietro Paolini belongs, in fact, to that group of photographers who, over the years, has slowly but steadily put the primacy of photojournalism in a crisis.

After the first trips to Venezuela – undertaken to tell the country and the populist phenomenon of Chavismo – Pietro Paolini felt a certain idiosyncrasy towards the Manichean scheme on which the photographic story is usually structured.

In Venezuela – says Paolini – everything is for or against Chavism and this large polarity, still represents a serious problem, a serious fracture and a form of division even within families. The same thing happens in documentary photography where there are two narratives, the one pro chavismo and the one against it. This extreme process – which is also found in the story of the country and in photography – required to take sides and choose a type of narrative either in favour of Chavez, enhancing his role as a revolutionary leader or against him, questioning him as a dictator, an extremely authoritarian figure.

I found myself repeatedly wondering where I positioned myself with respect to this dichotomy and, at the same time, wanting to get out of this pattern, from this opposition in which those who “pack” the story with a point of view already defined often fall. So I tried to keep a documentary outlook because what I was interested in was telling of the country but, at the same time, I tried to create open images, collect information, impressions that people could process more freely.

Basically, I was interested in turning my attention to the complexity of things, without necessarily having to judge. I was interested in a lateral glance, an open language that could bring up questions in the viewer without having to solve everything in an already predefined, “deployed” image, as often happens in the practice of photojournalism. With this, I absolutely do not want to stigmatize the photojournalistic story, since the diversity of languages can only be enriching, but underline my need to get out of this dichotomy and adopt different solutions.

Lateral glance, exploration, inquisitiveness, randomness, complexity: recurring terms in the photographer’s vocabulary, very indicative for understanding his approach and his visual response. An approach that is not free from philosophical implications, managed by the author with awareness and with considerable intellectual complexity.

Paolini often stresses – for example – the great power of chance in the definition of his language (he uses film and 6×6 format of an old Rollei since the digital camera he had brought with him on the road broke down), the absolute primacy of wandering and to go where his journalistic flair takes him but also the unexpected, the feeling, the light, the instinct.

He deems the phase of documentation, study and conceptual mapping of the territory as necessary, an acquired base from which to start the “great adventure of the gaze”, in search of the significant forms underlying the apparent chaos, traces and deposits of history in the marginality of reality and everyday life.

There is great attention in the book for the ancestral and strong relationship that exists in the indigenous culture between men and the Great Mother. But equally strong is the ability to reveal the profound contradictions of this idolatry, in the images that show the Pacha Mama wounded and raped by multinationals and extractivism.

The result is a photograph strongly imbued with magical realism, in its most contemporary sense, of a suspended and motionless time that is intertwined with analytical restitution of information and details. Photography capable of finding a balance between the outer and inner world, capable of mediating, as Luigi Ghirri cleverly wrote, between subjectivity and what is outside, which will continue to exist without us and will still be there even when we are done taking photography.

The book:

Pietro Paolini

Buscando a Bolivar

Witty Kiwi, 201

All images: © Pietro Paolini

May 20, 2019