by Daniela Mericio

_

There are places that everyone knows, even if they have never visited them. Immediately recognizable, made familiar to anyone by the countless images published in books, magazines, postcards, they are iconic places on the planet, classic or dreamed destinations, strongly present in our travel imagination: Notre Dame in Paris, Venice, the Grand Canyon, the Brooklyn Bridge, the Red Square in Moscow, Trafalgar Square in London.

In the Day to Night series, the American photographer Stephen Wilkes (New York, 1957) captured them, giving us suggestive and spectacular images: panoramic as far as the eye can see, traversed by light and shadows, similar to paintings with intense shades of color. At first glance, they might seem like landscapes in those precious moments of transition between daylight and darkness loved by many photographers, in that style that enhances the beauty of the sites, cloaking them in dreamlike splendor. Looking closer, it turns out that something doesn’t add up: inexplicably clear cuts of light, the position of the sun or moon on the horizon not always matching the other half of the sky, the same person is there several times in the same photograph: it is not the lucky recording of a “pivotal moment”, but the sum of many “magical moments” – as the photographer defines them – a succession of shots of the same place taken over the course of an entire day, over a period of time that goes on average from 15 to 30 hours, following the flowing of time and light, and then assembled into a single, amazing, final image.

Once it’s dark, the same landscape, the same city, reveal a different, antithetical face. Artificial lights replace the natural sources, people and rhythms change but the perspective is the same and captures the metamorphosis of nature, of an urban landscape, of human activities triggered by the passing of hours. Stephen Wilkes was able to concentrate an entire day in a single photograph: each final image, the sum of many others, contains the essence of a place, from dawn till dusk, and wants to record duration, to be the conscious visualization of passing time.

The creation of a photograph is very demanding. Wilkes, who defines himself as a street photographer from a 15 meters height, chooses an elevated position (usually a basket crane, if there are no suitable platforms on-site) able to offer a wide and satisfying view: after selecting the framing, he photographs an identical portion of space from the same position at regular intervals, without moving the camera, making approximately 1500 shots during the day. From these, then, he selects about fifty that will compose the final image, obtained through a meticulous and masterful post-production work that digitally merges the photographs. Even the assembly phase is a titanic undertaking and can take up to 4 months to get to the final result: it consists of infinite attempts and tests, and not only with the help of technology and Photoshop, as Wilkes prints the images, he compares them and put them next to each other to evaluate colors and shades, to verify the transition phases between day and night, to discover unexpected details.

In fact, despite the shooting phase taking place in a scheduled and timely manner, the unpredictable factors are numerous, starting from the weather. Above all, he can’t predict what will happen on the scene as the hours pass and what will be recorded by the camera; it is impossible to foresee which direction the cranes will fly in a nature reserve (Rowe Sanctuary, Nebraska), how fast the taxis will speed by in Times Square, New York, what the tourists will do in contemplation of the Grand Canyon, if the surfers on the beach in Rio will be swept away by the waves, who will pick the flowers in a Dutch tulip field or if someone in period costume would make their unexpected appearance at Stonehenge.

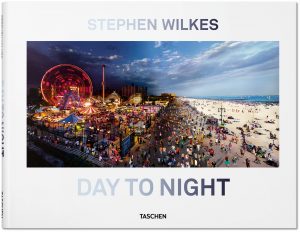

Infinite scenes and situations, not necessarily connected to each other, can be found in every image of Day To Night: each of them is like a Flemish painting to be analyzed in every detail (not surprisingly, Stephen Wilkes counts among his sources of inspiration Peter Bruegel and his painting The Harvest, 1565). For this overflowing wealth of details, the photographs of the series are appreciated above all if viewed in large format – in the exhibition or in the massive volume of the same name published by Taschen (2019) with 60 images, taken over the course of ten years. Ten years starting from 2009, when Wilkes photographed the Highline (the elevated New York path that runs along a disused railway) for New York Magazine and, not knowing whether he preferred its day or night face, he created the Day to Night technique, which allowed him to capture both.

The seed of this idea, however, had been planted in 1996, well before Photoshop and digital photography came into common use. Commissioned by Life magazine to photograph the set of the film Romeo + Juliet by Baz Luhrmann and failing to contain the square space of the set in an overview, he took 250 shots and joined them in a collage, obtaining an evocative photomontage in which not only different portions of space coexisted on the scene, but also different moments.

Wilkes is a storyteller, his photographs tell endless tales, all really happened and yet with an open ending; they offer countless ideas, they are an invitation to embark on a journey to discover many small worlds. Even, and above all, when the subject is a “historical” event or one that has a symbolic meaning for a community: Obama’s presidential inauguration in 2013, the Palio di Siena, America’s Cup in San Francisco (photographed from the breaking of day till dusk, from the top of a lighthouse on Alcatraz Island), the Easter Mass celebrated by Pope Francis in St. Peter’s (in the final image His Holiness appears a dozen times, in different phases of the ceremony, creating an actual narrative sequence).

Wilkes has photographed – often for National Geographic – beautiful places of unspoiled nature: in Canada, the valleys of British Columbia with its bears and killer whales at Robson Bay, colonies of seabirds on Bass Rock Island (Scotland) and in the Falklands, the Serengeti Park in Tanzania. Each photograph of the Day to Night series is built on the “vector of time”, the unfolding of the day and the path of light on a two-dimensional surface; a vector malleable like a fabric, which can follow a horizontal, vertical, even diagonal direction depending on where the author deems it more convenient to place the beginning and the end of the day on the final image.

Stephen Wilkes’ approach, however scenographic and spectacular, has a strongly contemplative aspect. It requires dedication, patience, observation and concentration. Examining and photographing the same place for a prolonged time, recording its metamorphosis and ever-changing details, “can be considered a form of meditation” says Wilkes, who defines the ability to look at things profoundly as “an endangered human experience.”

He reaffirms this concept in the caption that accompanies the image of the Sacré-Coeur in Paris, at the foot of which, on the Montmartre hill, a crowd of tourists with mobile phones takes selfies: “While shooting the Sacré-Coeur I witnessed all these people not looking at the monument at all. The act of sharing an experience has become more important than the experience itself.”

All images: © 2019 Stephen Wilkes

The book:

Stephen Wilkes, Lyle Rexer

Day to night

Taschen, 2019

March 29, 2021