by Claudia Stritof

_

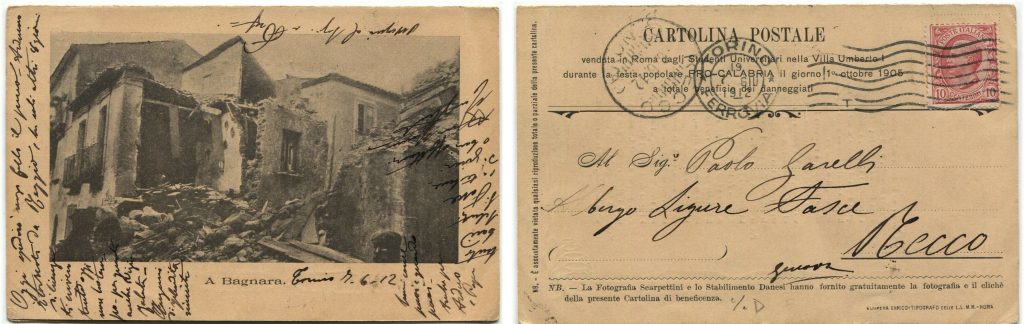

On October 1st 1905, the University Students of Rome organized Pro-Calabria, a charity event aimed at helping the Calabrian population hit by a devastating earthquake. During the fair, the boys sell folding postcards depicting the destroyed palaces of Bagnara Calabra, made thanks to Scarpettini Photography and the Danesi Factory which provided free photographs and clichés for the occasion.

The name of the publisher, Danesi, may sound new to many, but certainly not to the experts of the subject, in fact, Michele Danesi was one of the most important Italian printers of the nineteenth century, so much so that he became the first producer of illustrated postcards authorized by the government.

Our story about the postcard begins in these years, precisely in 1865, when Heinrich von Stephan, general manager of the Prussian post office, proposed the introduction of “an open sheet for short communications” at a discounted rate.

His idea, however revolutionary, did not find the hoped-for consensus, due to the violated confidentiality of letters; a problem considered secondary by the Austrian economist Emanuel Herrmann, who, following the publication of an article, convinced the Austro-Hungarian Empire to put the first “Correspondenz-Karte” into circulation on the now historic date of 1 October 1869.

The postcard was presented as an ivory-colored rectangular card with a printed stamp of the value of 2 kreuzers with the image of the Emperor and the space for the address on one side, while the back was left blank for the message.

As you can imagine, it was not long since the “naked” surface of the postcard was adorned with more or less elaborate designs, leading to the creation of the illustrated one. Regarding the latter, Enrico Melillo writes in Ordinamenti postali e telegrafici degli antichi stati italiani e del Regno d’Italia [Postal and Telegraphic Orders of the ancient Italian states and the Kingdom of Italy]: “Collectors and philatelists are struggling to trace the exact time it appeared […]. Some say it was the lithographer Miesler of Berlin […]; others that the publisher Martinazzi of Florence was issuing them since 1865; some give the authorship to the French stationer […] Leon Besnardeau […].”

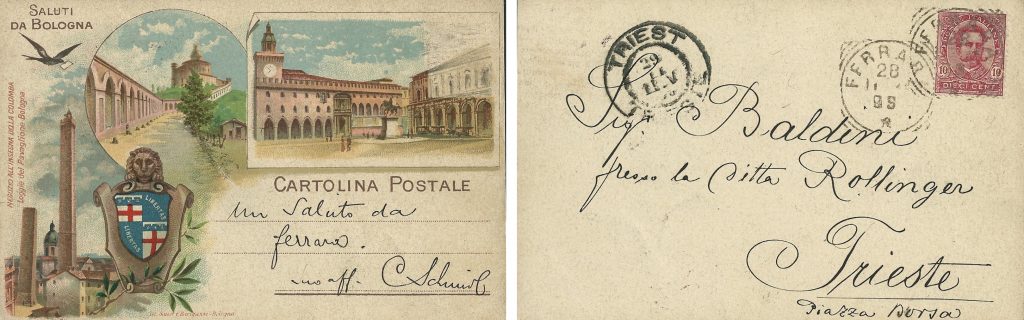

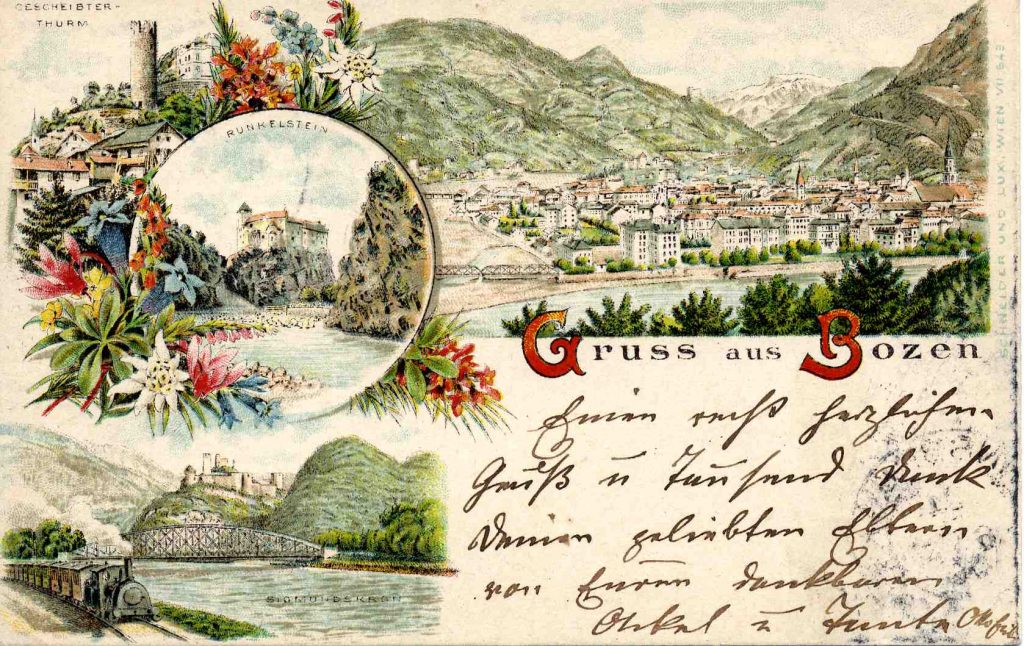

Like any story, even the postal one is dotted with anecdotes and claims on the birthright, and the evolutionary path that led it to assume its current appearance is still very long; just think that at the end of the nineteenth century the back of the card was reserved for the address, while the text and the sender were written on the side of the illustration, as in the case of the beloved “Gruss aus” (ie “Greetings from …”).

The postcard was a real publishing success, which grew further when governments authorized its private production and its destiny was intertwined with photography. Pioneering was the work of Dominique Piazza from Marseilles who in 1891 published the first series of photolithographic postcards; in Paris, the Neurdein brothers developed “a competitive technique for reducing the photographic cliché”, while the photographer Pierre-Yves created the famous company “Yvon”, a leader in the field.

Worth remembering is the Dresden publishing house “Rommler & Jonas”, created by the photographer Emil Römmler, a pupil of Joseph Albert himself, the inventor of the “albertotype”, while in Italy we had the aforementioned Danesi; Paolo Marzari, active in Schio, in the province of Vicenza, and last but not least, Saul David Modiano, whose activity is at the centre of the exhibition entitled “Il segno Modiano” – 150 anni di arte e impresa [“The Modiano Sign” – 150 years of art and business], curated by Piero Delbello for the IRCI of Trieste, at the Museum of Istrian, Rijeka and Dalmatian civilization of the same city. Arriving in the Friulian capital in 1868, Saul Modiano started the famous company, first dedicated to the production of cigarette papers, then opening up to other products, including postcards, which he illustrated with images taken during special photographic campaigns.

This is a very short selection of names active in the field which doesn’t forget the many local publishers and photographers who, between the end of the 19th and the 20th century, produced postcards depicting landscapes, monuments, and often portraits of their customers, specially made as souvenir photos to send to distant relatives.

From the moment of its appearance, the postcard has been a revolutionary medium, appreciated for its cheapness, and was entrusted with messages of well wishes, greetings, commercial orders, corporate advertising and even political and propaganda messages, like the ones used by the fascist regime, as evidenced by the series issued by the Italian Post Office between 1932 and 1936, extensively studied by Franco Filanci, President of the Italian Academy of Philately and Postal History. In addition, we shouldn’t forget its artistic value: as Filanci himself told me, since the end of the nineteenth century the postcard was used as an expressive medium by various artists. Famous was the case of Giovanni Fattori, who created a series of postcards for Richter in Naples depicting scenes of military life; up to, during the second half of the twentieth century, expressions such as Mail art, or 700 km di esposizione Modena-Graz by Franco Vaccari (1972).

In recent decades the postcard has undergone an inexorable decline, replaced by text messages and social networks that have inherited its functions and concept, but it has not been forgotten; just think of the numerous specialized magazines, the large private and public collections that preserve it, such as the “Salvatore Nuvoli” Postcard Museum in Isera, in the province of Trento, not to mention the exhibitions, begun as early as 1899, when the first International Exhibition of illustrated postcards in Venice was held. Last but not least, there are those who still produce them and there are many initiatives dedicated to them, such as the creation of the enthusiasts dedicated platform for exchanging postcards born within the FIAF – Italian Federation of Photographic Associations.

How can we forget the postcards sent to our loved ones from our school trips? A minimum of five and all different, many not sent, others instead arrived before the trip was over. The means change but not the habits, and today just a click and the tag of the place is enough to restore our “Gruss aus“, to show to our interlocutors the undertaken journey and how the days were spent.

March 29, 2021