by Claudia Stritof

_

Masayoshi Sukita is a silent man, of discreet movements and gentle manners, who answers questions in a timely and never predictable manner; after all, it couldn’t be otherwise, having shared unforgettable moments of his career as a photographer with the most important artists of the second half of the twentieth century.

Sukita was born in 1938 in Nōgata, in the prefecture of Fukuoka, Japan, in years certainly not happy for the country due to the outbreak of the Second World War. The event represents a dramatic turning point for him, since his father died in the war and it was down to his mother to take care of the education of their children as the family’s economic situation plummets.

Despite the economic difficulties of the family, Sukita asked to be gifted with a camera, a request that was satisfied by his mother, who understood the needs of the boy and the passion that animated him. It’s of her that Sukita takes the first photograph, a shot which already showed the refined and essential aesthetic that the photographer will reach in a very short time.

After graduating from the Japan Institute of Photography, he began working in an advertising agency, then moved to Tokyo in 1965, becoming an excellent male fashion photographer. However, it was during the trip to Osaka that he refined his style, taking on a well-structured language thanks to the teachings of Shisui Tanahashi, one of the most important photographers in the country, who was also proficient in landscape photography and art photography.

Sukita feeds on different cultural influences, looks at the Japanese world, but also at the emerging subcultures of the West. He wants to show the changes of his time: he takes part in the Woodstock Festival in 1969, the following year he is in New York where he takes some photographs at a Jimi Hendrix concert, in 1971 he portrays Andy Warhol and in 1972 he is in London to photograph the leader of the T-Rex, Mark Bolan.

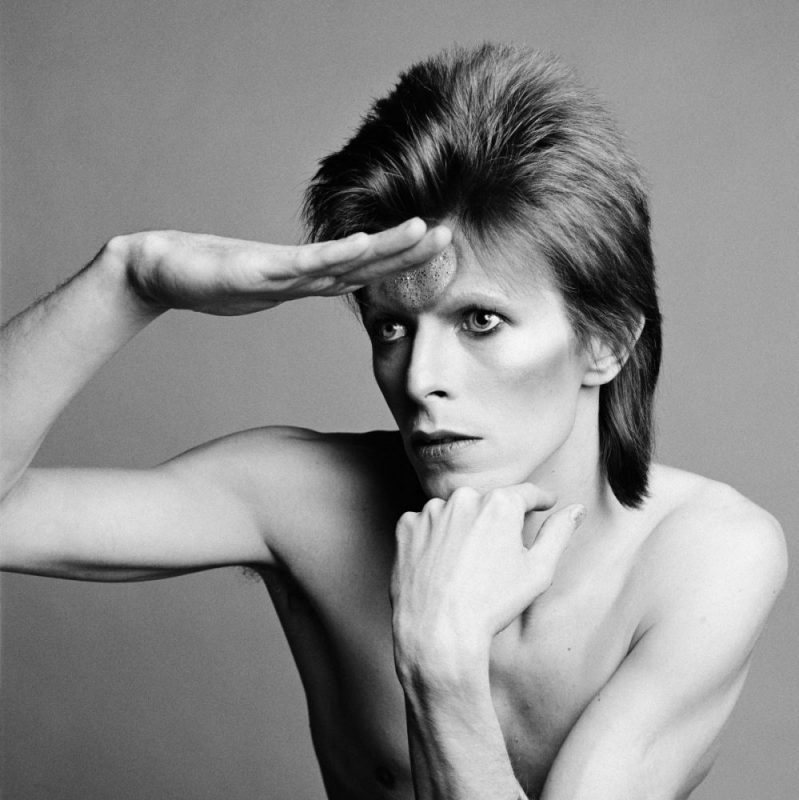

After an intense photoshoot with Bolan, the photographer sees the poster of David Bowie’s The Man Who Sold the World on the walls of the city, showing the singer with his leg raised against a black background. The image strikes him so much that he wants to go see a concert and, there, is blown away by Bowie’s creative genius, so much so that he wants to meet him.

A wish immediately granted thanks to his friend and stylist Yasuko Takahashi, who having collaborated in the first London fashion shows of Kansai Yamamoto – who had designed the stage costumes of Bowie during the period of Ziggy Stardust – gives Sukita’s portfolio to Bowie’s manager. The manager agrees to the shooting and, despite the language barrier, Bowie and Sukita start a solid professional collaboration, which over a short period of time will turn into great human esteem and devoted friendship.

In 1973 the two worked together again, both in the United States and during Bowie’s first tour in Japan, but one the most important meetings remains that of 1977 when they met in Tokyo for the promotion of the album The Idiot by Iggy Pop, of which Bowie was the producer.

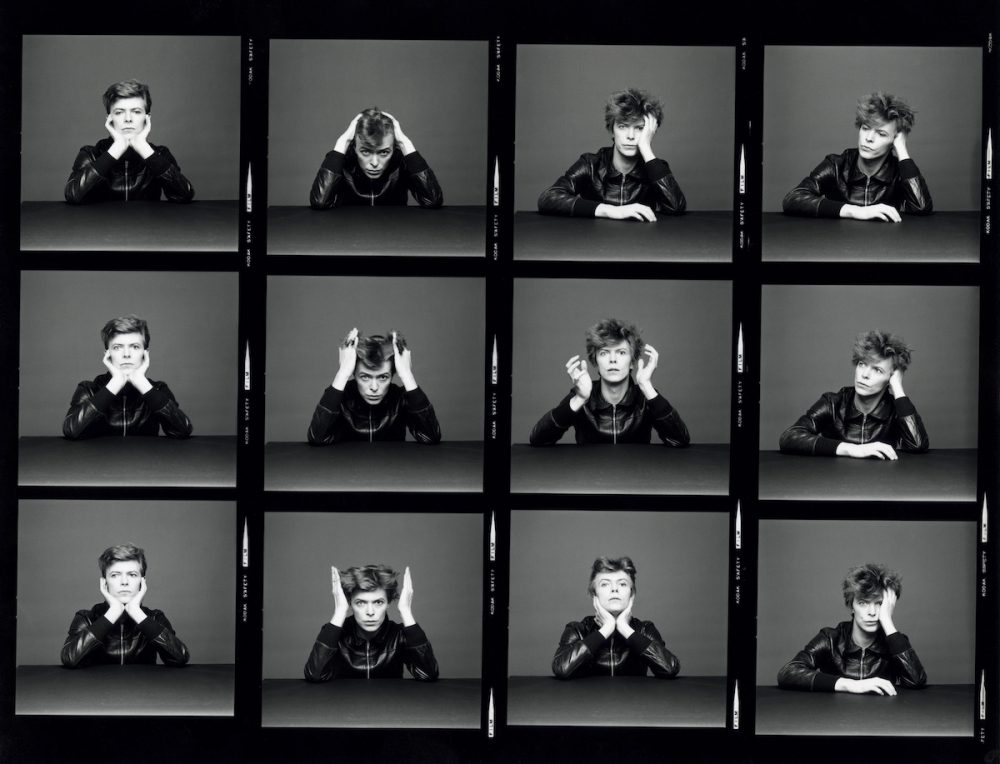

Upon hearing of the arrival of the singer, Sukita contacted him for a new shooting that would last about two hours, one dedicated to Bowie and the other to Iggy Pop. The atmosphere is relaxed and informal: Sukita catches Iggy smiling while wearing the typical Japanese wooden clogs bought in a city market, while Bowie is portrayed in black leather jackets against a monochrome background.

Sukita was impressed by Bowie’s great actorial skills, learnt from his mentor Lindsay Kemp: measured movements, great awareness of facial and body mimicry; he would ruffle his hair, assume painful, hallucinated and suffering expressions. What they didn’t know was that in one of those six films there was the future cover of Bowie’s Heroes, as well as that of Iggy Pop’s Party.

After the 1977 shooting, Sukita and Bowie met again in Kyoto in 1980. This time they did not shoot in the studio, but the singer – always an admirer of Japanese culture and traditions – wanted to experience the city, so the session took place on the subway, at the Kyoto traditional market and in the streets to then end in clubs, where they danced until late at night.

As the photographer tells in the book David Bowie by Sukita, after two days the singer expressed his desire to visit his Tokyo studio, with the idea and the project “to represent a contemporary clock, which would mark […] fewer hours than normal, to symbolize too hectic life and time that always ends up lacking”.

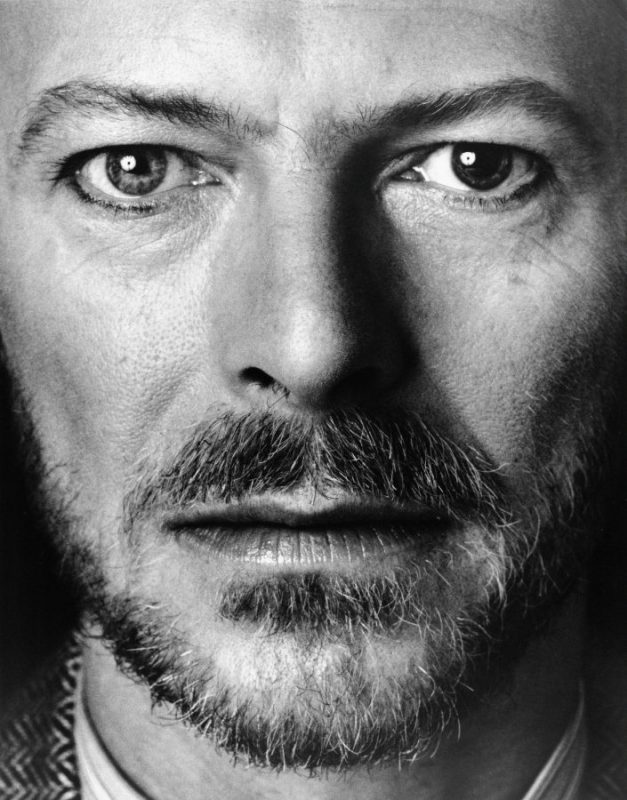

Many other were the photo sessions and – among all – Sukita recalls the one that took place in 1989 in New York, when, for the first time, he saw Bowie with a long beard hiding his beautiful androgynous face from him. After half an hour of shots, Bowie – always at ease – looked straight into the camera creating a very intense image, which, not surprisingly, Sukita entitled Ki, which in Japanese means “air”, “soul”.

Masayoshi Sukita’s photographs have now entered the collective image and many were the retrospectives dedicated to him. It was during his first solo exhibition in New York in 2015 that Bowie, unable to attend, sent an email to the photographer, calling him: “a brilliant artist […] a master”.

This was Bowie’s last contact with Sukita, because just over a month later, David Bowie died.

The Stardust Bowie by Sukita exhibition has just ended, curated by me together with ONO contemporary art, a gallery that for many years has dealt with the divulgation of the culture of music, cinema, fashion and, in general, all those icons that influenced popular culture of the 20th and 21st centuries. The exhibition at Palazzo Fruscione in Salerno wanted to focus exactly on those interrelationships, not only to trace the professional and personal relationship between David Bowie and the master of Japanese photography Masayoshi Sukita, but to underline how many are the forces that interact in a certain historical period and sometimes, with their union, initiate real cultural revolutions.

All images: © 2020 Photo by Sukita

March 6, 2020