by Manuel Beinat

_

Italy has its first international vernacular photofestival. GU.PHO will be held on 9, 10, and 11 September at the Castello di Guiglia, near Modena.

The event involves ten Italian and international artists – Erik Kessels, Alcide Cozza, Ivana Marrone, Sergio Smerieri, Alessandro Treggiari, Claudia Grabowski, Angelo Camillieri, Marco Trinchillo, Iana Bors and Anna Michelotti – as well as Leporello Photobooks from Rome, FRAB’S Magazines & More from Forlì and FOTO VIP from Modena.

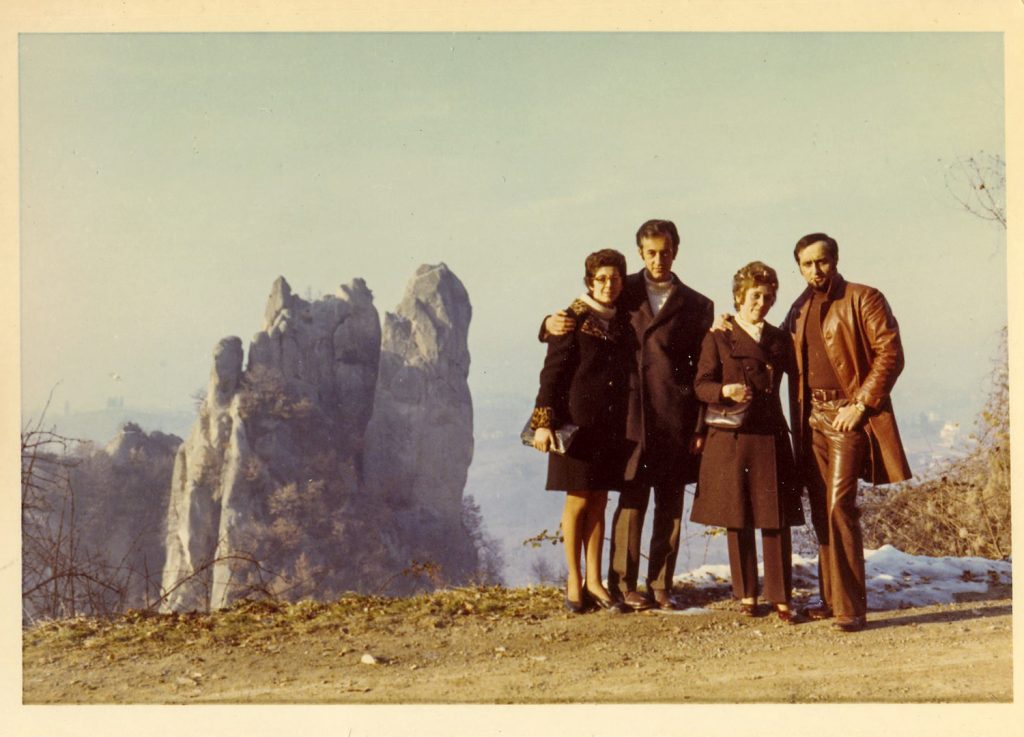

A three-days of study, exhibitions, talk and publishing event on the theme of vernacular photography, that is to say the set of images taken by ordinary (non-professional) people in everyday life situations, for personal use, where the aim is to innocently capture a memory, a special moment in their everyday life.

It is interesting to observe how in Italy, a country traditionally very attached to the concept of family unit and its most intimate and private dimension, we are only now beginning to give value to this type of practice.

Indeed, the festival’s intention is certainly to highlight, but above all to valorize vernacular production and its function as a collective archive, a mosaic of the past of our families and our habits since we’re living in a post-photographic era where they risk to be forgotten in a social and cultural amnesia. We must calmly accept it: what was once the family album, an object we all leafed through in the living room, is now a ‘dying’ device. The photographed moment is no longer even immortalized (considering the etymology of the term make immortal), but temporarily stored within the memory of our devices.

However, we must consider that the iconography of vernacular photography is based on criteria of representation that the digital will not succeed in canceling. Weddings, birthdays, holidays, travels, single or group portraits, smiles or sulks… whether from the 1960s or 2018, these common elements remain in all such photographs. The main distinction lies in the aforementioned presence (or absence) of an archive that can be enjoyed for years to come.

Vernacular photography is often associated with the past, with what has already been and can no longer be.

These images, whether they are ours or someone else’s, unlock cognitive mechanisms that trigger in us a strange bittersweet sense of nostalgia. They are reassuring images. They represent a sort of palliative to counteract the cold, liquid, multifaceted and unpredictable post-photography. Looking at them, we can reconstruct the stories of the people portrayed, we can play with our imagination and recompose the collective mosaic that is the history of us all. They contain many possible endings, happy or not, for all the actors, co-players and extras taking part in the great spectacle of vernacular photography. The photographic narrative bends and folds according to the beholder.

Here lay the fear of the lack of an archive, which would allow this game to continue. The presence of hard disks and memory cards, which can store many more images than the old albums, cannot fill the lack of that feeling of sharing and belonging to a family or group. It is this unconscious fear that prompts the viewer to look backwards, rather than set his eyes on what is in front of him.

Events such as GU.PHO Festival create a specific space for vernacular photography within contemporary photography and the so called post-photographic world.

International artists and institutions and events keep vernacular photography alive, preserving it, enhancing it, putting it in dialogue with contemporary productions, allowing new narratives to rise up.

Perhaps the archives of the future will consist of the same images as those of today, but the stories will continue to change, to be rewritten or rediscovered under different interpretations.

Have you ever thought about how many stories might be hiding in the albums, rolls and slides hidden in your cellars and attics?

More info on the official FACEBOOK PAGE of the festival.