by Dario Orlandi

_

On June 3, 1989, Dario Mitidieri is in Beijing to document the assembly of workers, students and intellectuals gathered for 6 weeks in Tiananmen Square to demand an opening of the Chinese government to civil and political rights. It is a peaceful demonstration to which the authorities initially seem to respond with dialogue.

However, on the evening of June 3rd, in a matter of a few hours, the situation precipitates: the square is invaded by the army that represses the movement with bloodshed, causing an as yet unspecified number of victims, arrests and injuries.

Dario Mitidieri is the only photographer to bring back to the West, in secret, images of the corpses crammed into the corridors of hospitals, making the seriousness of repression of the Chinese government known to the world.

The theme of human rights and their laborious affirmation is constant through the photographer’s long career, from the events in Tiananmen Square to the recent conflicts in the Middle East. We interviewed him for a reflection on the delicate relationship between rights and photography and on the role of photographers in the battle for their affirmation.

Did you return to China after 1989? What remains of the facts that you witnessed? Do people still talk about them?

Tiananmen Square is a taboo subject in contemporary China, even if you talk to modern and progressive people. During my last job in China, I asked my fixer, whom I was familiar with, about the facts of 1989. I replied: “Why, what happened in Tiananmen Square?” From the look on his face I guessed he was pretending … Even if the image of modern China is that of a technologically advanced country, the technology itself has become a tool for new forms of very sophisticated control (I am thinking of facial recognition systems or control over private chats) in some ways even more intrusive than before.

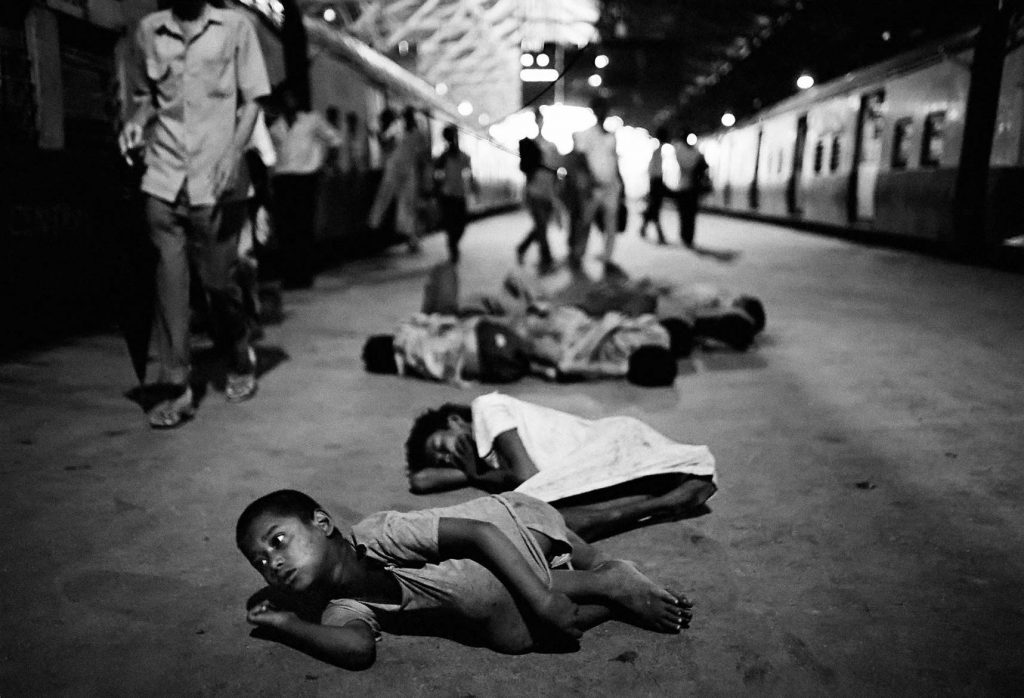

Looking at human rights in other situations, your famous book “Children of Bombay” talks about street children in the Indian metropolis in the early 1990s. What is your impression on the condition of street children in India and in the world?

The contemporary Bombay is very different from what it was, many degraded areas have been fixed up and modernized. This does not mean that there are no more children living in the conditions I documented 30 years ago, either in India or in other parts of the world. From Africa to South America, in many areas the problem has remained the same: difficult survival and adult violence.

The most difficult situations for children are the conflict zones, I talked about it in the Children at War series. Nowadays it is estimated that the Bekaa Valley, in Lebanon, is crammed with over 1 million refugees, among these there are many children, who will spend their childhood only knowing the reality of the refugee camps.

You talk about it in your last work on the Syrians fleeing the war, the one in which you built a photographic set in the refugee camps. How did this peculiar solution come to mind?

I asked myself how to give visibility to the many forgotten families of Syrian refugees of the Bekaa valley, at a time when the media was saturated with terrible images and it was very difficult to get attention on this story. To report the tragic consequences of the war on the lives of these people, I set up a series of family photos using a black backdrop and leaving empty spaces for the members who got killed or went missing during the conflict. Then I realized that by enlarging the frame and including the surroundings the photos got much stronger and more dramatic.

This is an example of an intelligent use of photography which has managed to break through and get people talking. When in your professional life did you feel that photography was really making a difference?

Certainly in the case of The children of Bombay: when I opened the exhibition, in a very fashionable area of the city, I rented a bus and brought 80 poorly dressed and dirty street children with me, thus creating havoc among those present. Another time, also in India, a report on paedophilia led to the arrest of numerous criminals.

Returning to Tiananmen Square, if we had not been photographers, the Chinese government could have continued to claim that there had been no deaths, as had happened a few years earlier in Burma. The same applies to Syrian families in the Bekaa Valley. When we asked the refugees what the most important thing was for them, they answered: “that you tell our stories, we don’t want to be forgotten”.

The path of rights is long and tiring, sometimes it even seems to go backwards. After so many years, do you still believe in the possibility of photography in this battle?

Absolutely. I fought throughout my career for human rights and could have done much more if I had found a more receptive editorial and communicative context. It was not enough to win prizes, produce books: I had to push hard to impose my will to do something, I often clashed with the very same organizations that were supposed to help me.

Some say that the exposure of suffering could be even counterproductive because it could anesthetize the public, making it indifferent. What do you think about it?

I do not agree: people must be hit with images because otherwise they tend to forget people and events that cannot be forgotten.

After the fall of Saddam Hussein, in Iraq, I made a report on the regime’s mass graves: they were the family members of the victims to ask me to show the world what had happened, as they went through the bodies looking for details to recognize their relatives.

If we had not been for us photographers, this story – like many others – would have been left untold.

DARIO MITIDIERI | THE LONGEST NIGHT

curated by Renata Ferri

Palazzo Ducale

Cortile degli Svizzeri 1, Lucca

PHOTOLUX FESTIVAL | 16 November – 8 December 2019

from Mon to Fri: 3:00 – 7:30 pm

Sat and Sun: 10:00 am – 7:30 pm

All images: © Dario Mitidieri

November 15, 2019