by Liliana Grueff

_

“Joyfully and childishly omnivorous artist” – according to the spot on description by Roberta Valtorta – Bernard Plossu is a cultured and prolific photographer. Completely immersed in a culture of the image such as the French one, rich in reflections and studies around photography, close to writers and critics (writers-photographers, to an extent, because they are personally involved with the practice of photography) such as Michel Butor, Denis Roche and Gilles Mora, Bernard Plossu is however alien to intellectualistic attitudes and favors an instinctive approach, where the camera is a life partner, a seismograph that records and allows perception, in direct contact with the emotion of the moment. For Plossu, photographing is acceptance, it means living, transmitting emotions; his empathic gaze rests on the things and people he meets and they give back images that radiate a special, suffused atmosphere. A great traveler, he has photographed and lived in various parts of the world; a few examples of his photographic production, very rich in publications and exhibitions, can be found here below.

Mexico, deserts, America

The desert is one of the recurring themes of his photography: Plossu traces his first encounter with photography to a trip to the Sahara with his father, when he was 13 and, later, he looks for other deserts and other landscapes in the south of the world and in the United States. In 1965, at the age of 20, he arrived in the United States for the first time (he would often go back after and even lived there for a few years), to travel across Mexico. This “on the road” journey, always a learning curve, passage of initiation and self-knowledge through the acceptance of what is uncertain and different, becomes, in the 60s, topic of the restlessness of a generation that rejects the established certainties, in society as in art.

Plossu walks the streets of Mexico with a borrowed Kodak Retina (nobody suspected yet that he would become a photographer), but above all with the baggage of images from his Parisian adolescence, from his long days at the Cinémathèque, where he discovered art cinema in black and white and the directors of the Nouvelle Vague, who were then carrying out a renewal of language towards a more direct and liberated cinema. In the photos taken in Mexico (later, when he was an accomplished photographer, with his own language) the modalities of his photography are already outlined: a technique and an aesthetic characterized by an expressive spontaneity that follows the pace of the journey. Alongside more “classic” shots, we find details, photos taken “casually” from the moving car, blurring, total or partial, strips of contact sheets (closer to the temporality of the filming flow of his beloved cinema). It is not a question of stylistic choices of deliberate transgression of canons, but of the expression of a work that, without hierarchies, follows the flow of travel and encounters, the movement of the time of life, and the images refer to us – as Denis Roche writes – that “current of sweet air” that has been blowing from Plossu’s photographs ever since.

After Mexico he became a professional photographer, started working for travel agencies and would return several times to the states of the American South West, finally settling, in 1977, in New Mexico where he will live until his definitive return to Europe in 1985. And since 1977, as he tells in an interview, he has felt the need not only “to show the world as it was, but also to make images for me“. He reserves the use of black and white for these photographs “for himself” and sets aside the discovery of a landscape of choice, that of the deserts of the United States.

“The American desert has changed my whole life. It started when, as a child, I went to see westerns on Sunday afternoons ” (…) When I arrived in the American Southwest, in the mid-1960s, I felt a great familiarity with this windswept, ocher and rough land. I was there, for real, the air was pure and the animals were wild”.

It is therefore with the memory of my fascination as a child, corroborated by the myth of the Native Americans (common in the counterculture of those years) that Plossu begins a systematic exploration, along roads and tracks that he travels on foot, of the deserts and mythical places of the Natives, in search of what remained of their culture and their land. The landscape he explores is therefore both mythical and real, an apparition and a confirmation. The desert is a “subtle” place where to enhance perception and listen to the silence, where the event is the changing of light and landscape, or the encounter with the sparse vegetation and the odd petrified trunk, sometimes the flapping of an eagle’s wings.

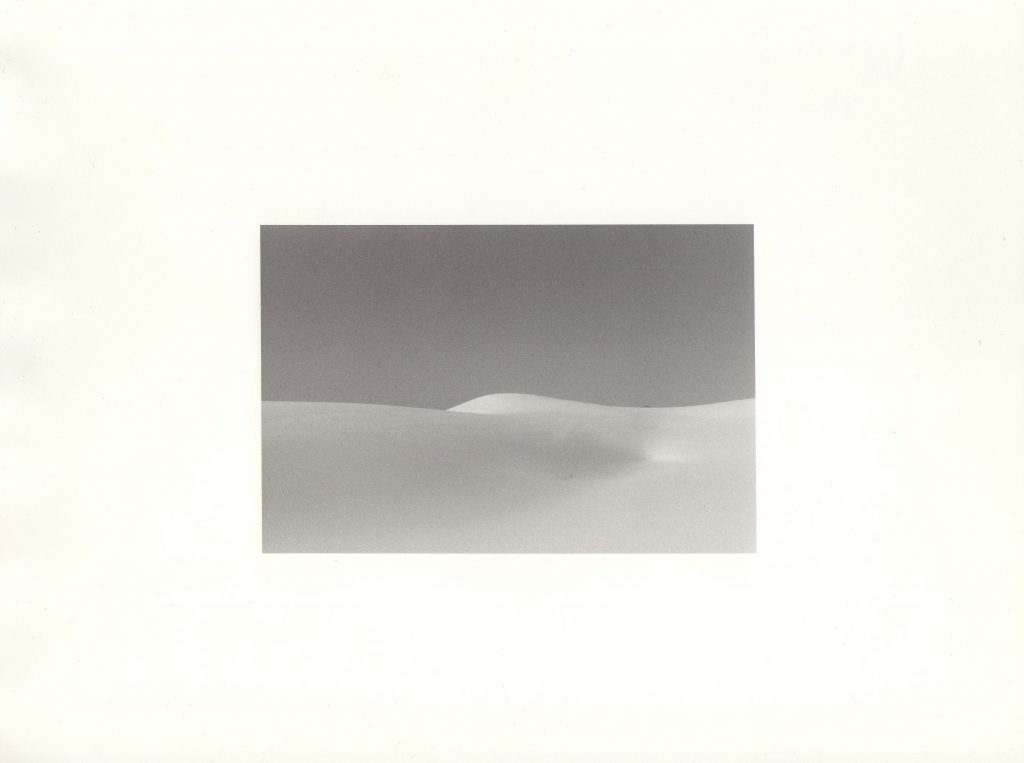

Plossu chooses to use a Nikkormat, with the “normal” 50mm lens (which he compares, for immediacy, to a shoulder camera) so that the images resemble what he sees as closely as possible. He prints his photographs in small format because the “condensation of light” that exists in a small photo expresses the essence of the desert. And because small images require you to get closer, to refine your gaze: they call for deeper thoughts, they express the sense of intimacy that can be found in the desert. Even in the book where they will be published, Le Jardin de poussière (The Garden of dust, 1989) the photographs are small and with a large white space around them.

A clear rejection, therefore, of the stylistic features of the landscape photo, from the large format to the monumental celebration, no “special effects” are used to render the silence of large spaces, the solitude, the long and slow time of the journey and of the changing light. They are rather minimal images, with a measure (derived from his love for Corot’s landscapes and for the luminism of Giuseppe Cavalli’s photography) that will constitute an expressive modality that will remain in subsequent works on the landscape and will coexist with images with an apparently more unstable frame, which characterizes another part of his work.

Another book testifies to Plossu’s American experience: So Long, vivre l’ouest américain – 1970/1985, published in 2007. It collects a tight sequence of images “on the road” of a journey that ends by the ocean. Heterogeneous images, scenes of urban life, details, collective moments and solitude, city and nature, photos taken from the car, “stolen”, according to the unstable rhythm of life and of the journey, and laid out by analogy – formal, of subject, point of view – or contrast. All with great freedom and a gaze that, while representing the moment of greatest closeness to American aesthetics, remains essentially that of a European humanist. A less disenchanted, more participatory gaze and a different sense of space that tends to structure even the most unstable images, differentiate Plossu from the American visual culture of the great names of street photography such as Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand or Robert Frank (to whom he has been often compared because of its autobiographical peculiarity.)

His images along American roads that seem to lead nowhere have nothing to do with the epic of the great spaces of the West, nor with the visions of the “New Topographers” who in those years were redefining American landscape photography in an anti-monumental sense, with unprecedented attention to the margins, the relationship with the artificial and the reflection on the photographic medium. As Lewis Baltz writes, Plossu, with a personal and solitary gaze, places himself there, on the edge of the two cultures, the French one of his origins and the American, from which he has learned styles and strategies of representation.

Trains, cities, black and white

After his return to Europe, he continues to travel, to look for deserts and landscapes to photograph. Under the banner of experimental happiness of the shot, of a libertarian irreverence, always tempted by imperfection and chance, he also photographs with “toy cameras” of unusual formats of which he appreciates the elementary nature of the mechanism that “allows you to go faster than your brain“. The recurring shots from moving trains or cars do not wish to be an intellectualistic reflection on the margins of vision and photography, but rather repeated signals of its coincidence with the fleeting, yet significant, impermanence of each image.

Col Treno [By Train] is the title of a 2001 booklet where the images taken from a train across Italy are accompanied by a text by Jean-Christophe Bailly – poetic prose with almost no punctuation – which flows like the continuous flow of images out of the window. Even when Plossu’s “journey” is limited to a city (Milan, Brussels, Athens, Bari), it is not the logic of the reportage to guide him, but the rhythm of his steps, an atmosphere or a light, his personal open vision, not premeditated (but not unsupervised either). Images from the car, fragments, encounters, to capture the atmosphere of a place, but also resonances, personal echoes. The work on Milan opens with a photo of his mother in the city – and with a tribute to Gadda’s writing and beloved images of twentieth-century painters, Sironi, Carrà, De Chirico, Morandi.

No “decisive moment”, no prospectively established hierarchy, but a flow of images Roberta Valtorta defined as “democratic” photography. All the moments are important, “intermediate” moments such as well as “intermediate landscapes”. And Intermediate Landscapes is the title of the anthological book (published in 1988 on the occasion of a retrospective at the Center Pompidou) borrowed from a novel by Michel Butor, writer (and also photographer) exponent of the Nouveau Roman or École du regard.

Having now set aside the historical diatribe on the relationship between painting and photography, photographers also turn to other non-figurative languages, to writing as an ideal companion for the images: in literature they find similar atmospheres, analogies and correspondences (a photography book – says Plossu – should not be looked at, but read).

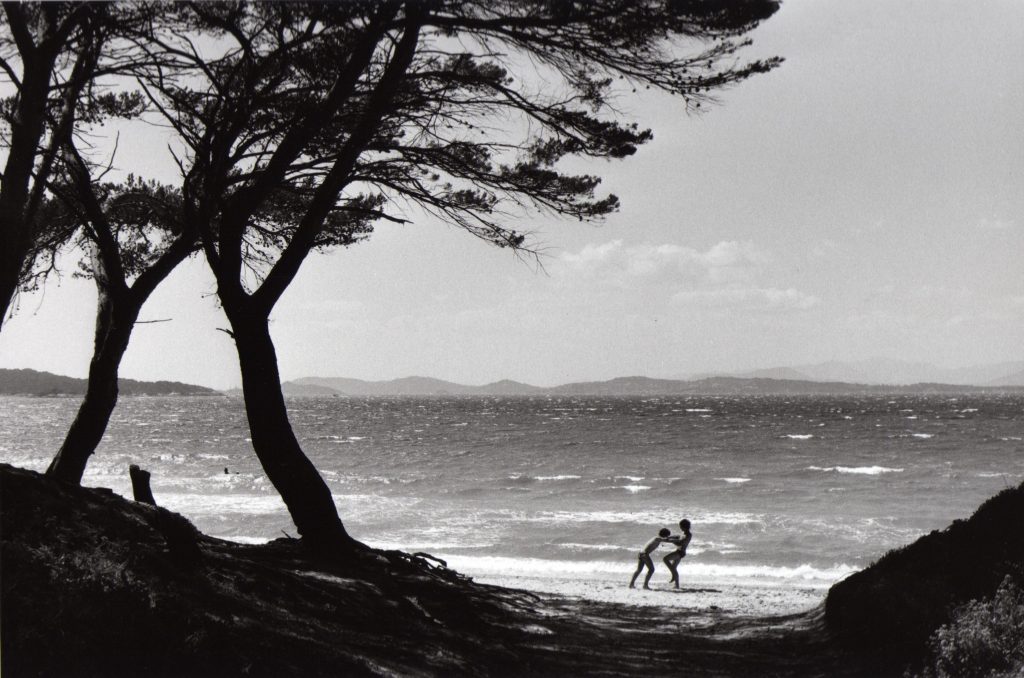

This is the case of many of Plossu’s photographs, in black and white – or, as he says “gray” – which he loves for his ability to translate the changes in light. The strong one of midday one, metaphysical, as in the photos of his favorite Giuseppe Cavalli, and the softer one of the afternoon, when the shadows appear, the grays become darker and become like a sensual “skin of the image”. Above all, says Plossu, “gray” gives a poetic dimension, it is a way of seeing as in a rêverie. In the rêverie evoked by Plossu we believe echoes of the speculations formulated by Gaston Bachelard in The poetics of reverie (1960) resound; and his camera is the instrument to realize that reciprocal relationship of gazes between subject and object of contemplation, to find the feminine in things, and to communicate their secret life.

Flou, color

Bernard Plossu mainly uses Nikkormat and soft films (like Kodak’s Tri-X). The grain blurs the edges, the image becomes soft focus and the things and people photographed acquire a special additional “presence”, in a suspended space and time. The soft focus does not so much signal a distance, a depth in a perspective space (as the limit of focus), but is instead the sign of closeness, albeit in a different space, the emotional one, in which his images lead us. The grain of the image is like a porous surface put on things by light, the soft focus a gradient of emotional intensity, which photography welcomes and activates. And the same porous surface we find in his color photos. Plossu uses a particular printing method, the Fresson printing, from the name of the family that has developed and that has been using a four-color process with the use of pigments (similar to carbon) for generations.

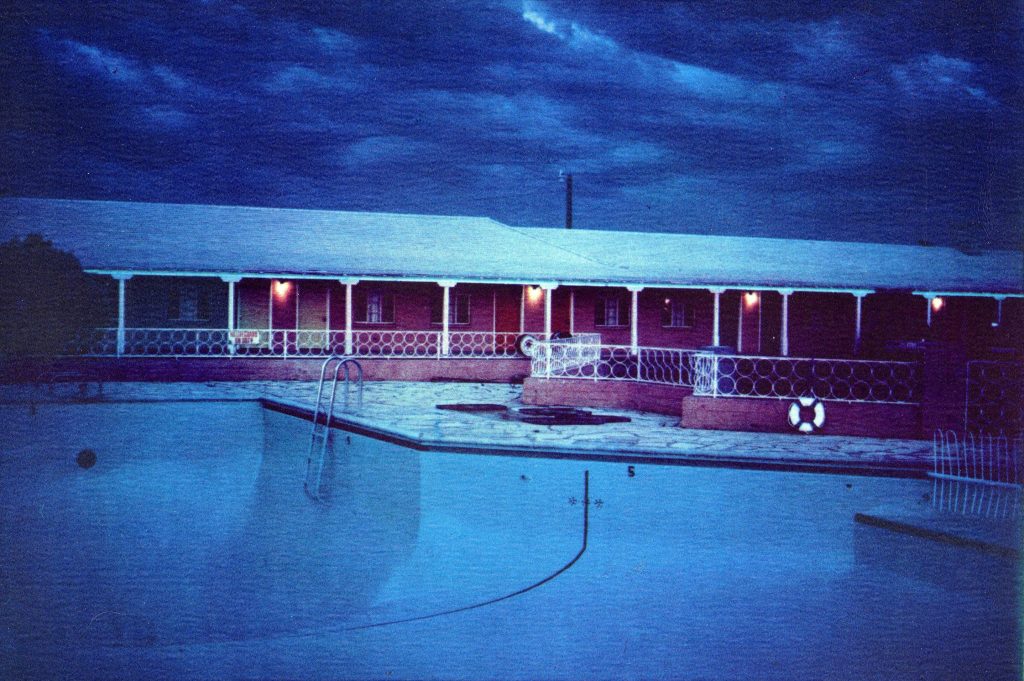

In Western Colors (2016) he offers us a color reinterpretation of the places he explored during his wanderings in the American deserts. If, as Serge Tisseron writes, “the soft focus is as much a sign of becoming as it is of a cancellation”, these images with fluid, grainy outlines, with colors that are more dreamlike than realistic, undoubtedly relate to becoming, to appearance. Or rather, they are the reappearance of an apparition, of the amazement that the author relives in his images.

If the pictorial effects of this procedure go in the direction of those “techniques of distancing” from reality (Marc Mélon, 1993) it is to get closer to the emotional and aesthetic reality of perception. The streets shot from the car, the drops of water and snow that mix on the window, the dust of the journey, of the arid and cracked earth, the rusty ocher adobes of the pueblos architectures and the dreamlike nocturnal blue are imbedded in the grain of the print. Immersed in a dusty light, these photographs reproduce that “skin of the image” of grays and that reverie of black and white photos, a porosity that, if it were not an oxymoron, could be defined as a tactile surface value; they certainly convey a deep, sensual joy of the image.

All images: © Bernard Plossu

March 29, 2021