by Claudia Stritof

_

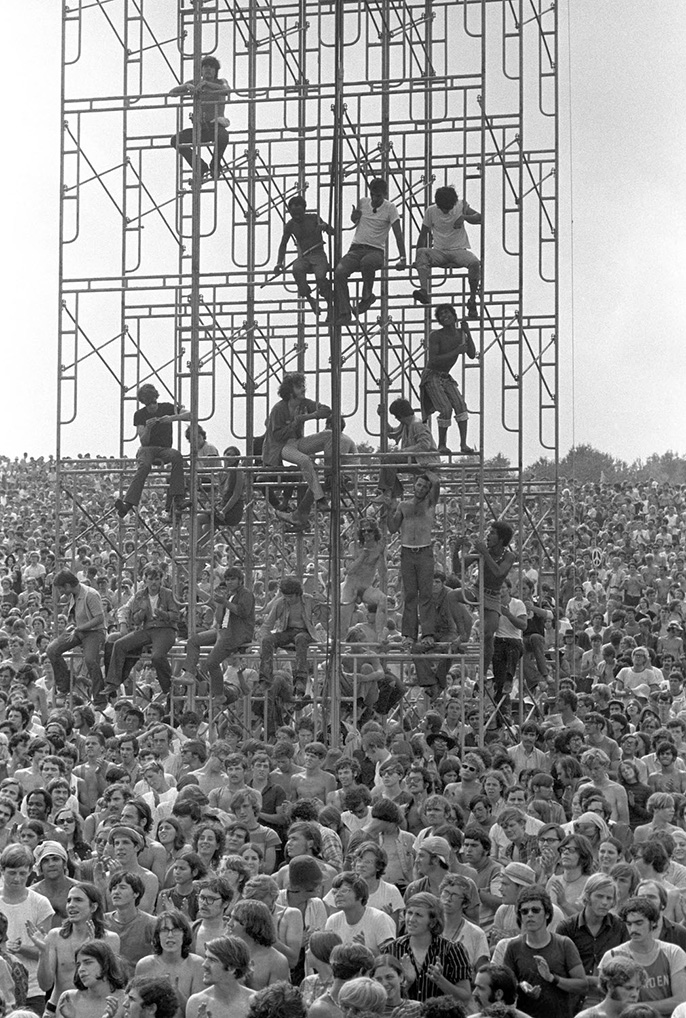

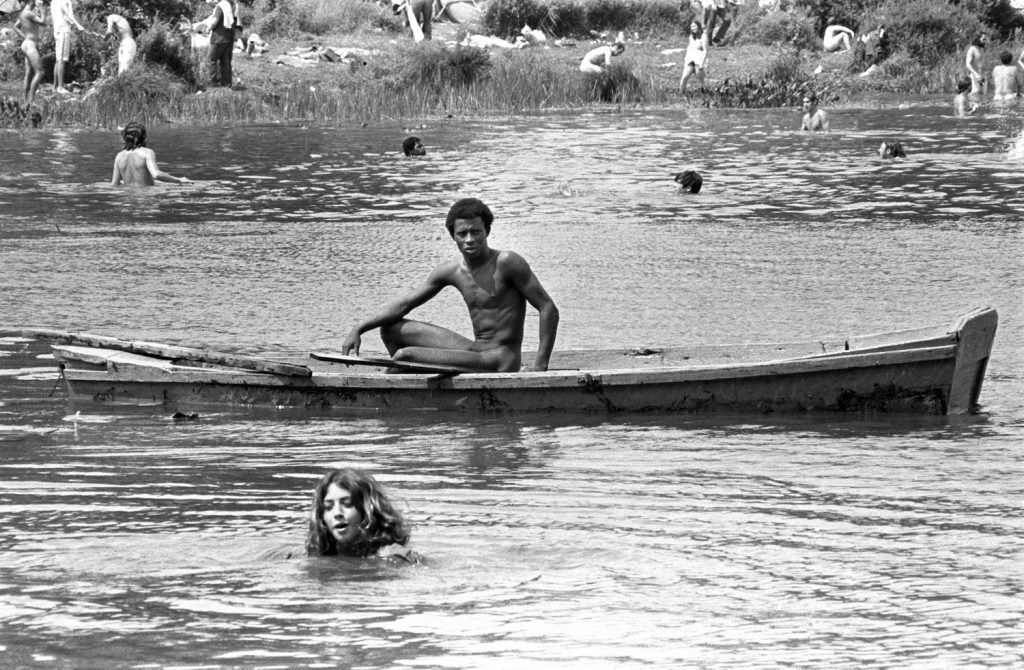

Woodstock showed that peaceful coexistence between humanity was possible […]

for this reason it is important not to forget.

(Baron Wolman)

The Woodstock festival, held between 15 and 18 August 1969 in Bethel, a small town in the state of New York, was not only a musical event or a hippie gathering, but a shared message of love and peace, spread through the universal language of music. An ideologically powerful message, which contained the hopes of those young people who took part in the festival and whose behaviour, so different from those of their parents, was nothing more than a way to distance themselves from business orientated and warmongering politics. A disconnection between old and new values that clearly emerges in the images of Baron Wolman, at the time chief photographer of Rolling Stone magazine, who clearly recalls the atmosphere of Woodstock.

Baron arrived in Bethel thanks to a project on music festivals that he was carrying out together with photographer Jim Marshall. Music festivals at the time were prevalently dedicated to country music and jazz, while rock was still quite marginal; in fact, as the photographer himself recalls, they heard about Woodstock for the first time in June, deciding to add it to the list, because after all “it would have been just another music festival among the many that we were photographing”. They did not imagine that soon they would witness a unique event of its kind.

As chief photographer of Rolling Stone, Baron Wolman had made himself known for his straightforward style which he used to portray the many musicians of the time, but in Woodstock, once he embraced his Nikon, he decided to turn the lens towards the people. Everything was new and amazing: nobody wore sneakers, there were no T-shirts with logos, the cows roamed freely in the fields, the cars laid abandoned along the way; people shared meals, meditated and bathed naked all together.

Baron’s shots are imbued with symbolism and mythology, they are the portrait of an entire generation and, photograph after photograph, they show us what the atmosphere of Woodstock was, as well as the great organization of the festival, which had been structured in different areas, all arranged around the huge stage: the camping area, a smaller stage for those who wanted to perform for free, the free kitchen, the market space and the health and care facilities, which were entrusted to doctors, professional nurses and also to hippy communities, who gave psychological help during bad trips caused by the use of LSD and other substances.

As much as the legends are exciting – and the three days of Woodstock is studded with it – the idea of the festival was born as a well-structured event, whose story begins when John Roberts, Joel Rosenman, Artie Kornfeld and Michael Lang decide to form the Woodstock Ventures, a company whose aim was not only economic, but also utopian.

The day before the festival, on August 14, 50,000 people were already there, many of them without a ticket, so the decision to make the concert free seemed obvious to the promoters. When the barriers were knocked down, the assistance and first aid facilities began to prove insufficient and the rain, although light, began to fall on Bethel, but the most serious problem was the roads, jammed with cars that did not allow the bands to arrive in time to perform. At 17.00 the first notes that were heard were those of Richie Havens, a musician who wasn’t scheduled to perform, followed by Guru Swami Satchidananda and then by Country Joe McDonald, sent on stage with a borrowed guitar.

Although the line-up was completely gone, the atmosphere was proving magical and Woodstock was turning into a myth to tell future generations. The bands were inspired and the public felt it, the feeling – as Baron said – was that of “500,000 people all together shaking off the chains of what conservative society expected of them”.

After the first day of the festival, the hygiene conditions in the area were poor, the toilets unusable and the food insufficient; despite this, people were happy, thanks to the humanitarian spirit of the young people who started a shared self-management. Unfortunately, the second day also began with the death of Raymond Mizak, crushed by a tractor while he was asleep in his sleeping bag. A tragic event that attracted the attention of the media and which, combined with the horrific hygienic conditions, caused the whole area to be declared “disaster area”. The alarm turned out to be the salvation of the organizers, because it allowed them to receive assistance from the government thanks to the army planes that arrived in Bethel.

The concerts began at 12.15 and on stage played, among others, the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin and, late at night, The Who with Pete Townshend who ended the concert by shattering his guitar. By then, singers and bands alternated seamlessly on stage, the instruments, due to the humidity, went often out of tune and the empty moments were filled with debates, yoga sessions and prayers.

Sunday was opened by the notes of the Jefferson Airplane and closed with those of David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Neil Young and Graham Nash, but the rain was now incessant and people began to leave, although many other bands were yet to perform. On Monday, August 18, at dawn, there was the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, followed by Sha-Na-Na, until at 9 in the morning, a group of faithful admirers was still waiting anxiously for Jimi Hendrix’s arrival. The three days of peace, music and love ended with the notes of his guitar.

Woodstock was all this: a daydream, a moment of collective love, in which there were no barriers, no gender divisions and even if it was only a beautiful illusion, as it probably was, for a few days it turned into a wonderful reality made of trust and sharing of ideals, because, as photographer Baron Wolman said, Woodstock represented “the promise of a world without violence, a world full of peace, respect and compassion and, yes, also of love”. Woodstock “ended too quickly”, because after this utopian experience – adds the photographer – “the world quickly returned to its imperfect self”. Capturing the spirit of time is a rare gift, but Baron Wolman has succeeded in this titanic undertaking, leaving us today with an important legacy of visual and oral knowledge, through which we can feed our dreams for tomorrow.

All images: © Baron Wolman

March 6, 2020