by Chiara Ruberti

_

And I wondered once more just how delicate the boredom of a single horizon can be.

Luca Bertolo

In this last year, the few times that I have managed to travel, the horizon that opened up just outside the borders of my municipality seemed to me like an exotic, exciting, unrepeatable destination.

Not to mention the joy, so true and liberating, of when I was able to look at that so familiar line where the sky meets the sea, thinking that sooner or later we will be able to cross it again, on the discovery of unknown horizons.

In the background, the sea extended, high on the horizon, and a slow sailing ship passed by.

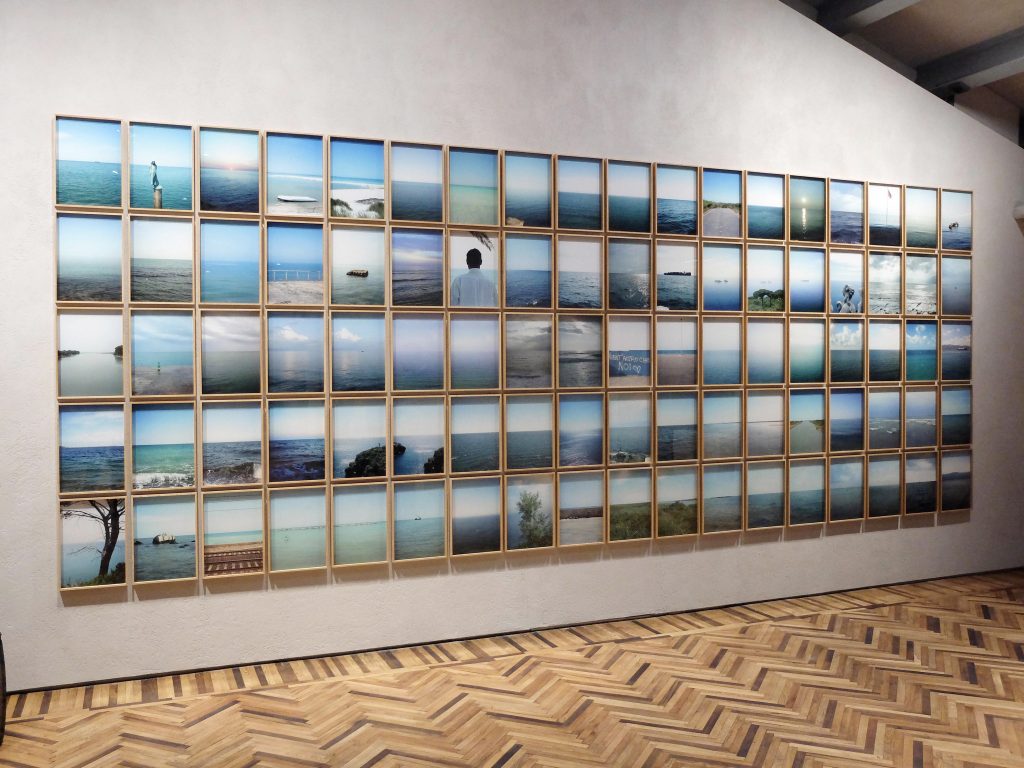

Italo Calvino, The Baron in The Threes

A bit like the elk tree for Cosimo, the pandemic has irremediably changed the perspective from which we will look at this old battered new world, from now on. But it hasn’t changed the strength of memory and in mine, there is always a place for Antonio Rovaldi’s work. For the poetry and strength of that wall that closed the opening exhibition of the Osservatorio Prada [Give Me Yesterday, curated by Francesco Zanot, December 20, 2016 – March 12, 2017] and which resonated with me, pulling the heartstring of my visceral belonging to the coast, but which interested me above all because it added a piece of fundamental meaning to the entire exhibition, courageously – and genuinely – interrogating the photographic medium. In an exhibition that explored the contemporary outcome of photography as a personal diary and which gave great space to very young authors and to the short circuit generated by digital technologies and sharing platforms, Rovaldi’s work managed to condense time and emotion, suddenly ceasing to chase them. The result of a slow and thrifty accumulation, his images, like the notes of a delicate musical score, were arranged on the wall, opening up a world, which was at the same time the trace of an experience, personal and circumscribed, and of an imaginary world, collective and boundless.

Rovaldi made a long journey by bicycle in 2011 along the coasts of our country from Trebiano (Liguria) to Trieste (Friuli Venezia Giulia) – for a total of 3514 kilometers, 180 bananas, 38 120 Kodak 400 color films, 1 film Hilford HP5 400 black and white and 148 photographs. This is the material that constituted the first core of his work, to which in 2014 he added what was produced during the trip, always by bicycle, along the coasts of Sardinia, collected in the series Mi è scesa una nuvola.

The precious volume Orizzonte in Italia, published by Humboldt Books and the MAN of Nuoro in 2015, collects images, notes, drawings and intense and inspired words, from that of Francesco Zanot to that of Pier Luigi Tazzi, which I found here with a little surprise and much pleasure with Soste (e) Marine. The volume is sold out and we hope that it will soon be reprinted.

In the meantime, I would like to ask the author to allow me a short dance between and with his images, to tell me something more about his work.

I was born in Pisa; a 15 minutes drive to Bocca d’Arno, with the Apuan Alps as a backdrop and the view that when you are lucky, in winter, stretches to Cap Corse, is beautiful. In half an hour you can be in Calignaia, the clear water, the ocher rocks, the oil tankers and behind the promontory of Castel Sonnino the sea of childhood and the Quercianella pier. In an hour and a half you are in Abetone and on the top of Monte Gomito, on the clearest days, you can count all the islands of the Archipelago. A ferry and in four hours you are in Bastia in Corsica, what more can I say? If you cover it all and cross the Strait of Bonifacio there is Sardinia; if you go down to the extreme south there is Cagliari, the Pisan area, and the Capo Ferrato Camping where for a thousand summers I watched the full moon rise over the sea, upside down.

And I have always looked for the sea, wherever I went wandering. In Greece, I looked at it but only a little and mostly because the marvelous remains of an ancient civilization were doing it for me, like at Cape Sounio. In Portugal and Mexico I met the ocean, the Atlantic, the one with the scary voice, but once you get to know it, sharks aside, it’s not really that scary. In California I listened to the Pacific, deep and solemn like the whales that swam it and immense like the son who already lived inside me when I found the courage to jump in. Many others are the seas of my life, but these are the most important.

You were born in Parma, the sea there perhaps can be seen from the peaks of the Apennines. What is your sea? Which is your island?

The Sardinian writer Marcello Fois would say that in the plain there is no sea – as he wrote for Sardinia in 2008 – and Marco Belpoliti, in his latest book, that the plain is a world. On the plains, where I grew up, in winter the fog rises and they say: “tonight we see little nothing, there is a sea of fog”. In recent years the fog has dissolved and the landscape has become monotonous, we no longer witness epiphanies.

On the plain, where I cultivated my first glances, I have always seen the sea. A white sea, rising and falling, covering and revealing the landscape. It could be said that we, people of the plains, have grown up in a sea of revelations. It sounds emphatic, but that’s a little bit like that. The sea, the real one, where I used to go as a boy – and where I still go when I want to disconnect from Milan – is the sea of eastern Liguria, where I have a house overlooking the Apuan Alps and where I left for my horizontal journey in spring 2011. I left home early in the morning from Trebiano and, when I took the first state road by bicycle, I realized that I was carrying too much. I went home going up the hill, I emptied the bags and went back down. Orizzonte in Italia was a continuous stopping, weighing and starting again, many km a day, countless stops to photograph the horizon and write down what I saw in a red notebook: the time of the shot, the number of the film, the weather of the day. During the trip, I ate 180 bananas and I took many more than the 148 photographs you saw at the Fondazione Prada but in the end, you know, you always have to make a choice. My island is the place to which I return and from which I always leave: the house and the studio where I mature and think over projects.

The rigor of your work – with that horizon line always in the middle of the rectangle, with the gaze that always turns to the sea from the earth – gives life to a song that, far from being monotonous and repetitive, opens up to the unpredictable, because in your images there is nothing predictable, as Zanot writes, “from the frequency of the waves to the shape of the clouds, up to the colors of the water of which both are made”. Not to mention everything that remains out of the frame, which each of us from time to time, image after image, look for in memory, in imagination, in experience, in stories, in dreams. Dunes, pine forests, tracks, scenic roads, monotonous promenades, chimneys, villages, cities, mountains, hillocks, kiosks, umbrellas, trunks, children, old people, silence, laughter, perfumes.

As in an extreme synthesis of the photographic medium itself which is an instrument of reproducibility par excellence, given the possibility of obtaining infinite copies from the same matrix, but also a means through which it will be difficult to obtain two identical frames.

Photography never repeats itself, just as the opposite is true. Who has never photographed a horizon, the sea, the sky, a mountain, or kept a diary? Each photograph, if taken a short time after the previous one, in the exact same position, will always be different. There is always something that moves in the landscape; the sea, from afar, appears motionless but in reality it is always in motion. The earth does not stop and the one who decides to look at a portion of the landscape at a precise moment, for more or less time, selects a point among an infinite constellation. Maybe the images are like stars. You look at them, you believe that they are talking to us about a specific place, about what you have in front of your eyes, but in reality they are suggesting another space, another time that is behind us, or further ahead…

These days I often return to the title of a book by John Berger: And our faces, my love, brief as photos. A love letter. An amazing little book!

Photography, like the things of life, is an act that implies a choice: you have to decide what goes in and what should be left out. Sometimes, photography can be annoying.

Orizzonte in Italia is a complex image that has formed over time, through an accumulation of gazes. The image of that long sequence of marine horizons is always a partial look at a geography that changes constantly, because the first to change it’s us looking at it. For example, I would like to retrace the same journey as in 2011, but from the opposite side. Sometimes I think I could do the exact same thing, back and forth, east to west, west to east, as long as I have the strength. It would always be a different image. It is a question of punctuation, of pauses, of rhythm. Landscape is a distance and a time, just as a distance and a time are contained in the photographic film. When the film ends, in a certain sense the landscape in front of you also ends. Obviously I am saying this as an author who, before organizing a project, cultivates a complex image in the mind, a desire that wants to find a form. This is a concept that contains multiple directions and all very broad and does not concern only the representation of the landscape through the photographic medium, but our way of crossing, staying and being in places. Our reflection on things. Our faces, too, as light as photos.

The bicycle and photography, different tools used here for the same purpose: to travel a distance. On the one hand the road under the wheels and perhaps a red line on a map, on the other a series of photographs which, arranged in chronological order, draw an unpublished, and unknown, profile of Italy.

I wish I had done this. For example, that time, many years ago, when I rode the entire coast of the Peloponnese on a blue Vespa 125. But I have already lost many of those horizons. But that’s okay, you collected them for me, even if they are not exactly those.

Two days ago, rearranging my archive, I found among heaps of paperwork a project by my artist friend Rä di Martino entitled Works that could be mine and works that I would like to be mine. Rä had asked artists what were the works of other artists, dead or living, that they wished they had done. I replied it was the last – and definitive – work of Bas Jan Ader In Search of The Miraculous. Now, in retrospect, I’m glad it wasn’t me who set out on that unstable boat from Cape Cod on July 9, 1975 – I’m content to think I was born on the same day that year – because Ader never made it back and the remains of his wrecked boat were found the following year along the Irish coast.

This is also to say that I am very pleased that you would have liked to have created Orizzonte in Italia. After all, there are some images that really belong to everyone in equal measure. If a work hides a truth, somewhere among its thousand stumbles and second thoughts, this then becomes everyone’s territory and each of us is free to place himself within it. Eugenio Turri, a geographer whom I have always loved, read and reread over time and whom I regret not having been able to meet in life, would say: Landscape as theater.

And yes, Chiara, I too have wondered how delicate the boredom of a single horizon can be.

But that’s okay for now!

All images: © Antonio Rovaldi

March 29, 2021