by Francesca Catastini

_

I have known Aurelio for about fifteen years and I was his assistant for ten. It was certainly a significant experience, beyond photography, and when I hear him talking about his artist friends and his relationship with them, I can’t help but think of our friendship as well. As soon as I could, I went with him to visit the anthological exhibition that his city, Pistoia, has dedicated to him, open until 25 July. We briefly talked about it afterwards.

How do you feel every time you come back to visit the exhibition?

Every time I think my city has honored me with a great gift, even if they say it was me who did that to them. Few authors are lucky enough to have an anthology exhibited in their city.

And in this lifetime, too!

Yes! Unbelievable!

Let’s say you gave each other a gift then. But, gifts aside, what kind of feelings does it stir in you, are you satisfied?

Of course I’m satisfied. At the same time every time I get emotional, I see my life, and I remember many friends. In an hour, an hour and a half, fifty years of history flow in front of me, a history which is also my own. It affects me and makes me melancholic, I think back to the many moments shared with my friend Burri, with Gianni Dova, Fazzini, Manzù … and with many others. I have grown deep relationships with artists. Usually, when I go to see the exhibition I always take a friend with me, because otherwise I feel too much nostalgia.

You have become friends with most of the artists you have photographed. Unfortunately, some are dead while others, like Michelangelo, you have not been able to know for obvious reasons. But you also established a friendship with them, a human relationship, right?

Absolutely! With Michelangelo we are good friends, so much so that he was also pissed off when I photographed Bernini, but then, like all sincere friends, he forgave me.

Bernini is not a friend, he is more of an acquaintance, right?

Yes, he is more of an acquaintance. With Michelangelo I made seven books and exhibitions all over the world, with Bernini I made a beautiful book for Treccani, but it is normal for the relationship to be different. Let’s say that my relationship with Bernini is a bit like the one I had with Warhol, I have seen and photographed him twice. Then I was never able to talk to Warhol, except with gestures and nods of the head. As I moved his works to portray him he nodded his head because he understood what I wanted to do and he liked it, but I never learned English and he didn’t know a word of the dialect of Pistoia… With almost all the other artists I have portrayed instead, I have a sincere friendship, there are some that I haven’t photographed for a long time, but with whom I often speak on the phone, such as Finotti and Antonio Recalcati. Unfortunately, many are no longer here, and I am no longer a kid myself…

When you went to an artist’s studio to photograph him did the fact that you were there change anything in their way of working? I don’t mean that they posed or amplified their gestures for the camera, but that maybe, somehow, even unconsciously, they were influenced by your presence…

No, no, maybe a little bit at first, there could be a bit of embarrassment, they had to get used to it, then, as time passed, they almost forgot about me. We talked often, then we had coffee during breaks. Sometimes I even posed them as soon as I saw something I liked. There was a great intimacy. A few times I brought my assistants along, but with Burri I was almost always alone, otherwise something would have changed. I have always chosen to photograph them in their atelier: my portraits may even be less refined than those made in the studio, against a backdrop, but they speak of the artist’s life. Some ateliers were full of cobwebs, in others there were colors scattered all over the floor, like in that of D’Orazio, who had a wonderful studio. There were those who had a tidier studio and those who did not, but they were all beautiful just as they were.

What is your study for you?

You spend your life there, you are always there. It’s like a second wife, or perhaps even a first.

The studio itself is almost a portrait of the artist, like that photograph, which I like so much, in which you see Nitsch’s chair and the shoes he wears when he works laying on the floor. You feel the presence of the artist, his personality. And, as you said, Burri in his studio is more Burri than Burri in front of a white wall.

Exactly.

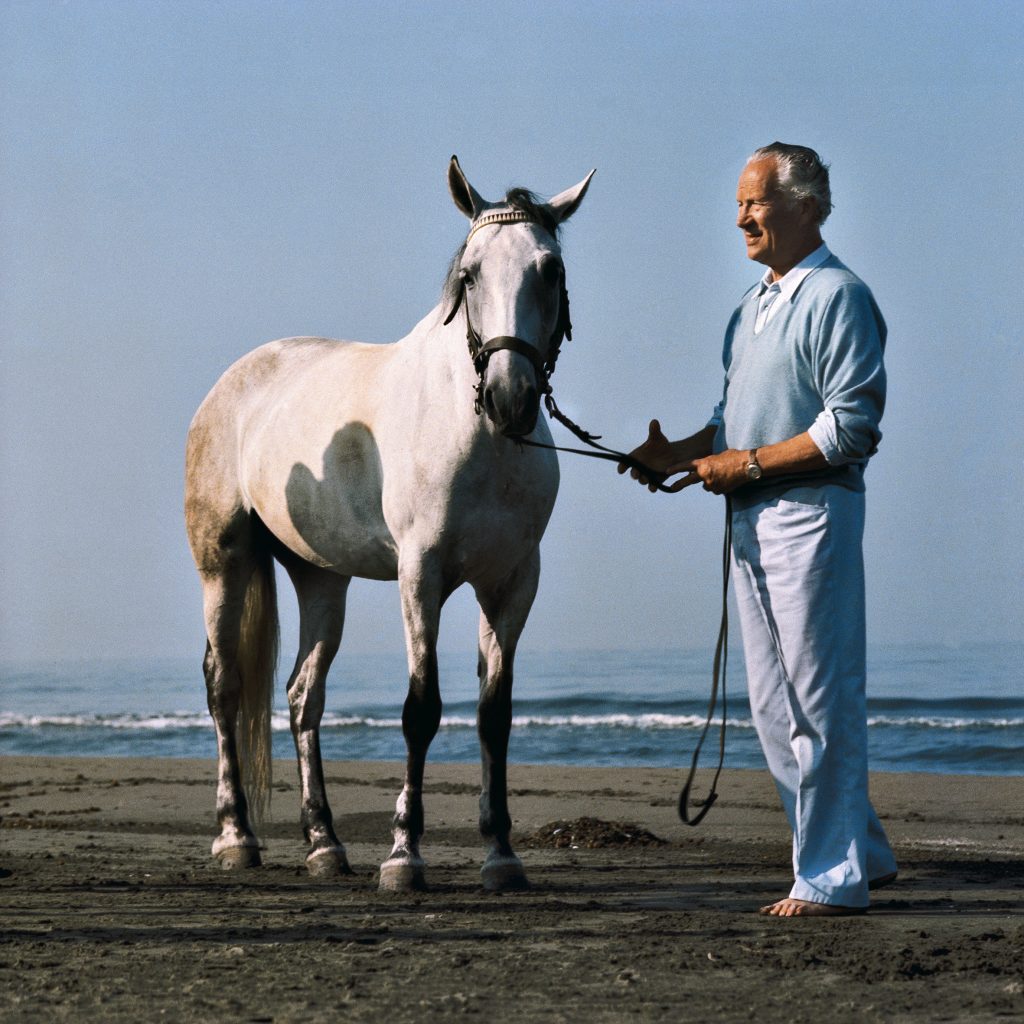

You always photograph with a sense of respect for the artist and his work, but there is so much of you in your images. I’ve never seen you take a photograph that doesn’t reflect your way of seeing. It is from there, in my opinion, that the relationship of trust between you and the artists you photograph arises. You don’t interfere, you don’t intervene, but when you propose something or express your point of view, they know there is a reason, and they listen to you. Like when, in 1972, you asked Giorgio De Chirico to get on a gondola to photograph him in front of the Doge’s Palace, or you stopped a bride in Venice and photographed him shaking her hand, or when, in 2003, at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Bologna, you told Parmiggiani, dressed as a diver, to start from the center and not from the outermost part of his Labyrinth, to destroy it with a hammer, or again, ten years later, when you proposed to Ceroli to wear the wings that he had made and to go to the seaside to take his pictures.

Yes, I have never wanted or tried to override the artist and his work, but I have always expressed my ideas and I must say that they have been welcomed every time, there has always been a personal relationship and deep trust, not only with friends but also with the artists I met when I was still very young, like Giorgio De Chirico.

What is sensuality for you?

For me, sensuality is everything in photography. It is linked to beauty, far from vulgarity. In sculpture, I manage to bring out the sensuality of the work, almost to the point of showing something that those who admire the sculpture itself cannot see with the naked eye and without my lights. It is above all in sculpture that I see sensuality. Maybe I’m better at photographing sculptures than people.

In your work, sensuality does not emerge only in sculpture. I am not referring to eroticism, but to the search for certain sensations, a certain sinuous delicacy that caresses the eye…

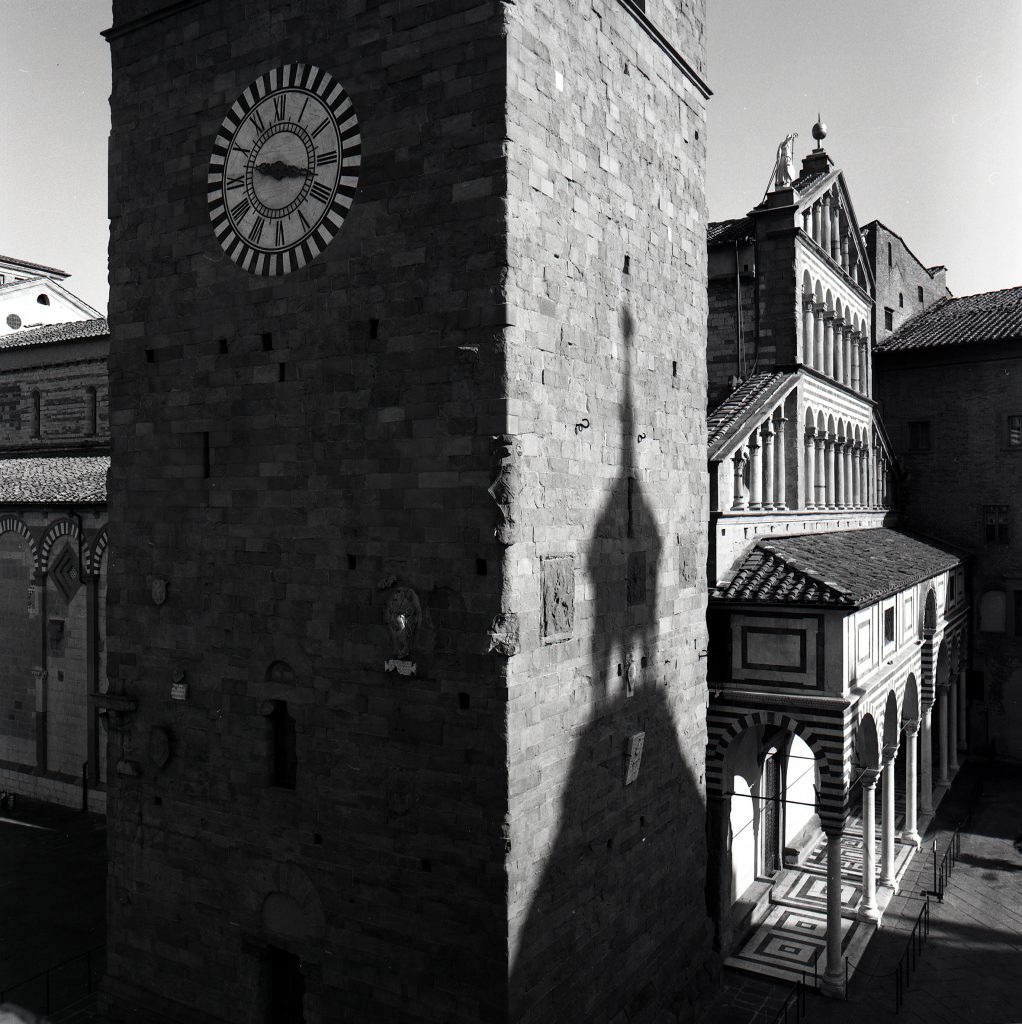

In sculpture I look for sensuality through my lights, in architecture I expect the right light to arrive to get what I want. I also see sensuality in my images of San Pietro or San Galgano. San Pietro’s Basilica without people: it took me a year to finish that job, and there I really tried to show all the sensuality of that sacred place. It was the same for San Galgano, for the Duomo of Milan, for my city, Pistoia, and for the Cretto di Burri.

In fact, you often look for that exact type of light, that cut, a grazing and warm light that recalls that of the spotlights you use to illuminate the sculptures.

Precisely!

The light is a bit like a chisel, then…

The lights that I add with the spotlights, or that which I Iook for when I wait for the sun to arrive exactly where I want, change the perception of the photographed subject, whether it is Michelangelo’s David or the altar of St. Peter. In some ways, it is as if you sculpted the forms of architecture or of the sculpture itself. For me, yes, it’s a bit like giving a few strokes with a chisel, à la Michelangelo.

And in the portraits of the artists?

I don’t even see the bodies of the artists.

In my opinion you see them all right, because every movement is different from the other … And you choose the gestures to immortalize very carefully.

Okay, but I don’t look at the artist’s body like the body in sculpture. They are moments with the artists, when I photograph the sculpture I am more concentrated, the sculptures do not speak, they do not move, they don’t fuss… I am not a photojournalist, in fact my photos, compared to those of others, are static, see Burri, Warhol, then in the Happening series there is more movement.

Let’s talk about Pistoia, how was it to photograph your city?

On display are my friends, Bolognini, Vivarrelli, Barni, Ruffi, Buscioni, friends from the beginning; there is a sequence of Marino Marini when he came to Pistoia with his twin sister. Then there are the architectural photographs and in particular the series on Piazza del Duomo. Photographing my city was challenging: I know it so well that it is more difficult for me to find something that I have never seen before. I try to photograph things that are not usually seen, such as empty squares. To the question “Maestro, why do you always paint empty squares?” De Chirico replied “Because I get up early in the morning”. I too get up early and at 5 in the morning I was already in Piazza del Duomo.

What does it mean for you to make others see something that they would not see on their own?

Well, it is the photographer’s job in my opinion, otherwise what is he doing? In the case of the artist’s atelier, it is also about space, because there was just me, the others had no access. With sculpture, on the other hand, I transform it with lights: people see my photos of the Medici Chapels and return to visit them to find those angles that they had previously missed. I show others what I see, I do it for myself too, because I photograph things as I see them, it’s a bit of a portrait of mine too, I’m there too.

Can you tell me something about The Absolutes? It is something new, which you exhibited for the first time on this occasion, right?

Yes, that’s right, I call them “experiments”, it’s a new work. I had in mind the project of The Absolutes for about ten years already, but I had never done it. Recently, friends from Giannoni & Santoni offered me to print them on concrete panels, through a process that involves the use of plaster and fibers. We worked on the printing process and the materials, thought about the various cuts and how to display the panels, and I must say that I am very happy with the result.

In conclusion, this exhibition traces your entire career, but is there a photograph that you would have liked to have in this exhibition and that for some reason you were never able to take?

That of Picasso. In ’72, or ’73, my friend César called me to tell me that he had made an appointment with Picasso to photograph him. I got in my car and drove like a madman to get to Saint-Paul de Vence as soon as possible. As soon as I arrived I went to dinner with Yves Montand and César, both originally from the province of Pistoia, Montand came from Monsummano Terme and César from Pescia. I was there for Picasso, but the morning after I arrived we were told that he had fallen ill and that we had to postpone. I stayed for several days, hoping to be able to photograph him, while waiting for him to recover I played bowls with my two friends. Unfortunately, however, there was no way to meet Picasso.

The exhibition:

AURELIO AMENDOLA

An anthology. Michelangelo, Burri, Warhol and the others

curated by Paola Goretti and Marco Meneguzzo

Fondazione Pistoia Musei, Pistoia

Palazzo Buontalenti

8 February- 25 July 2021 / extended until 7 November 2021

via de’ Rossi, 7Antico Palazzo dei Vescovi

Piazza del Duomo, 3

8 February- 25 July 2021

Mon-Fri, 14:00 – 19:00

Sab-dom, 10:00 – 19:00

July 19, 2021