by Daniela Mericio

_

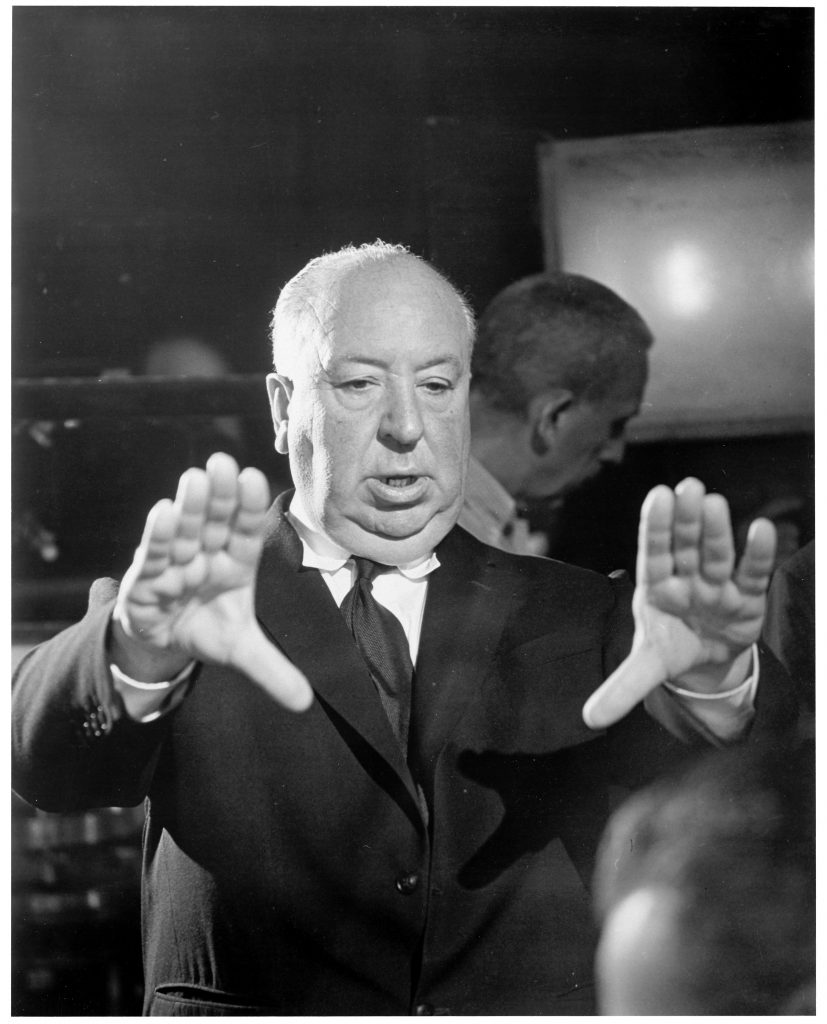

The thing that strikes me and excites me about Hitchcock is his ability to think visually, without having to resort to words. […] His unique, extraordinary, inimitable ability to communicate and excite using simply and only images.

(Gianni Canova, Alfred Hitchock. Cinema at the edge of nowhere, Skira, 2019)

Francois Truffaut already noted this peculiarity in Hitchcock/Truffaut, where we find the French director’s interview with his British colleague, held at the Universal Studios in Hollywood over the course of a whole week. The book, published in 1966 [French title: Le cinema selon Alfred Hitchock, “Cinema according to Hitchock”, Ed] is a declaration of love towards the master of suspense, at a time when the reviews on his work were contemptuous and harsh. Truffaut underlines how many filmmakers delegate the narration to a stream of words, entrusting essential details for understanding the plot to the dialogues between the characters; a cascade of words, heard but not seen by the viewer, who loses the plot, gets distracted, as the illusion of being inside the flow of filmic events gets broken.

According to what he defines as an essential law of cinema, Truffaut concludes: “All that is said instead of shown is lost to the public” and makes a comparison between the inadequacy of the directors of the word and the mastery of Hitchcock, unsurpassed in making us understand a situation through a shot, a juxtaposition of frames or a simple game of glances. The essential, allusive dialogues and the absence of unnecessary connecting passages in the narrative, make Hitchcock’s films “without holes or stains” as he used to say; films in which there are no “privileged moments”, in which every minute is significant, visually eloquent. This allows you to keep the attention and emotional tension high, creating the well-known, inimitable suspense.

Beyond the obsessive care for the image, the shots that could teach a lot even to the best photographers, what does Hitchcock have to do with photography? In Truffaut’s interview book, “Hitch” reveals: “When I was studying engineering, drawing was my favourite subject and photography after that”. And it was precisely through drawing that he landed on cinema: before going behind the camera he drew titles and captions for silent films – in the 1920s there was still no sound – for an Anglo-American production house (the Famous Players-Lasky). The English director also claims to have been fascinated, since he was a boy, by photography in American films, superior, according to him, to those of his motherland. However, there are no noteworthy photos taken by Sir Alfred Hitchcock, and in fact this article was not programmed. By chance, however, a photographic exhibition dedicated to him opened – until January 2021 – at the Arengario in Monza, forty years after his death, which prompted me to review some films and reread something more about this brilliant author and communicator.

The exhibition, curated by Gianni Canova, tells the story of cinema through photographs, taking us by the hand, in a light and fun way, in the exploration of the Hitchcock universe. On display are set and backstage shots, taken during the making of the films of Universal Pictures, the major with which “Hitch” met his destiny after moving to Hollywood. The 70 photographs, identical in size and rather small, are arranged in succession, perfectly aligned, divided by movie. It is like skipping through a photo album without having to turn the pages, as if the images were frames of a film that we could stop and analyze, recalling what we have already seen on the screen, making connections and peeking, from time to time, at the set. The setting reminds us of a cartoon, a comic strip that ironically reconstructs the “character Hitchcock”, the one who has managed to fascinate millions of viewers not only with his films but also thanks to his personality, his humor tinged with anxiety and ability to probe the human soul with a hint of sarcasm and pity.

The rich captions alternate technical details, historical information, trivia, behind the scene; are accompanied by videos in which Gianni Canova, with profound simplicity and lively acumen, tells of the man, the director, his art and style, focusing on the subversive force of Hitchock’s gaze, which sees beyond the bourgeois milieu in which his films are set: “Hitchcock revealed to us that the ordered world where we believed we lived is nothing but a shapeless chaos and that apparent order is only a mask destined to crumble”, despite a “dull criticism” which has considered him for years “a worshiper of useless and dangerous toys, a puritanical and complex fat man, obsessed with crime, blood and sex”. Until the masters of the French Nouvelle Vague shifted the perspective, calling him “one of the greatest creators of forms of the entire twentieth century” (Claude Chabrol and Eric Rohmer) or counting him among the “restless artists” whose mission is “to share their obsessions”, unwittingly helping us “to know each other better” (Truffaut).

In the exhibition we can learn more on the behind the scenes of some of the most famous and beloved films of the English director, films that have become a cult and a reference for years: Vertigo (1957), full of mystery and ambiguity, Psycho (1960) and Norman Bates’ troubled personality, The Birds (1963) which introduced many innovations in special effects and shooting techniques; and again Shadow of a doubt (1943), Rope (1948), Marnie (1964), up to the director’s last work, Family Plot (1976). And of course, Rear Window (1954), box office record-breaker with an irresistible James Stewart and a sophisticated Grace Kelly. Critics have written various essays on this film and its theoretical, conceptual, philosophical implications, each time finding new nuances to analyze. Maurizio De Bonis (La vertigine dello sguardo, Postcart, 2013) places it “in a wider territory than that of cinema, a territory that concerns the visual arts of the twentieth century as a whole” defining it, together with Blow up by Antonioni, a pivotal step in the theoretical reflection on photography.

The protagonist is an assault reporter, Jeff, on a wheelchair due to a broken leg, the result of an accident at work. From his tiny New York apartment which, along with many others, overlooks an inner courtyard, Jeff spends his convalescence observing neighbours. With the aid of a powerful zoom lens – and binoculars – he looks from inside other houses and the unfolding of existences in their daily routine, until, in his long observations, he realizes that a crime has been committed.

The film is studded with allusions and clichés regarding photography and the figure of the photojournalist. “Penniless photographer who never has a dollar in his pocket” as Jeff defines himself while his classy girlfriend asks him: “What is it in travelling from one place to another taking pictures? It’s like being a tourist on an endless vacation […] And it’s ridiculous to say that it can only be done by a special, private little group of anointed people”. Jeff does not act, he just watches, and when he is discovered by the murderer he defends himself with flash shots, using the work tool as a weapon. The nosy housekeeper calls the camera a “portable keyhole” and the photographer a voyeur, a peeping Tom. However, it is evident that Jeff comes to expose the killer thanks to a combined action of mind and eyes, sight and thought: it is as if the director suggests that the gaze is not enough to interpret and decode the world if it is not supported by intellectual skills.

What does Hitchcock have to do with photography? Nothing, except that, again quoting De Bonis, Rear Window should be interpreted as “a meta-cinematographic essay on the sense of seeing, on the value of the technological representation of reality and on the strong intertwining between optical device, eye and processing capacity of the mind. Only by activating this function (not measurable), Alfred Hitchcock suggests with sharp reasoning, it will be possible to understand the true nature of the photographic discipline and its relationship with the sphere of reality.”

All images: © Universal Pictures

ALFRED HITCHCOCK. Nei film della Universal Pictures

curated by Gianni Canova

Arengario

Piazza Roma, Monza

9 October 2020 – 10 January 2021

Wed 2:00 – 6:00 pm

Thu and Fri 10:00 am – 1:00 pm / 2:00 – 6:00 pm

Sat, Sun and holidays 10:00 am – 6:00 pm

The exhibition is temporarily closed to the public due to the Covid-19 emergency. For further information and online insights please consult the exhibition organiser’s website.

November 10, 2020