by Daniela Mericio

_

Peace, a dream of serenity that humanity has pursued over the centuries but that the world seems far from having reached because –and we are all aware of it, at least partially – every area of the globe is experiencing daily conflicts and violence, with different levels of intensity and drama. Peace and justice (and solid institutions) is the target number 16 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, signed in 2015 by the governments of the 193 UN member countries. Of the twelve “targets” set for the goal, the first one simply says: “Significantly reduce all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere.”

Photography has played and continues to play a fundamental and irreplaceable role in showing what happens in places devastated by wars and terrorism, documenting conflicts and their consequences with reports capable of shaking the collective conscience. The ways of the photographic medium and creativity, however, can be infinite: there are works that have left their mark by telling of a reality torn apart by horror without describing it objectively, managing to communicate the atmosphere of pain that accompanies a tragedy without showing the most evident parts; revealing the less visible aspects, hidden between the folds of reflection and introspection and leading the viewer to an area where photography expands its boundaries and joins art.

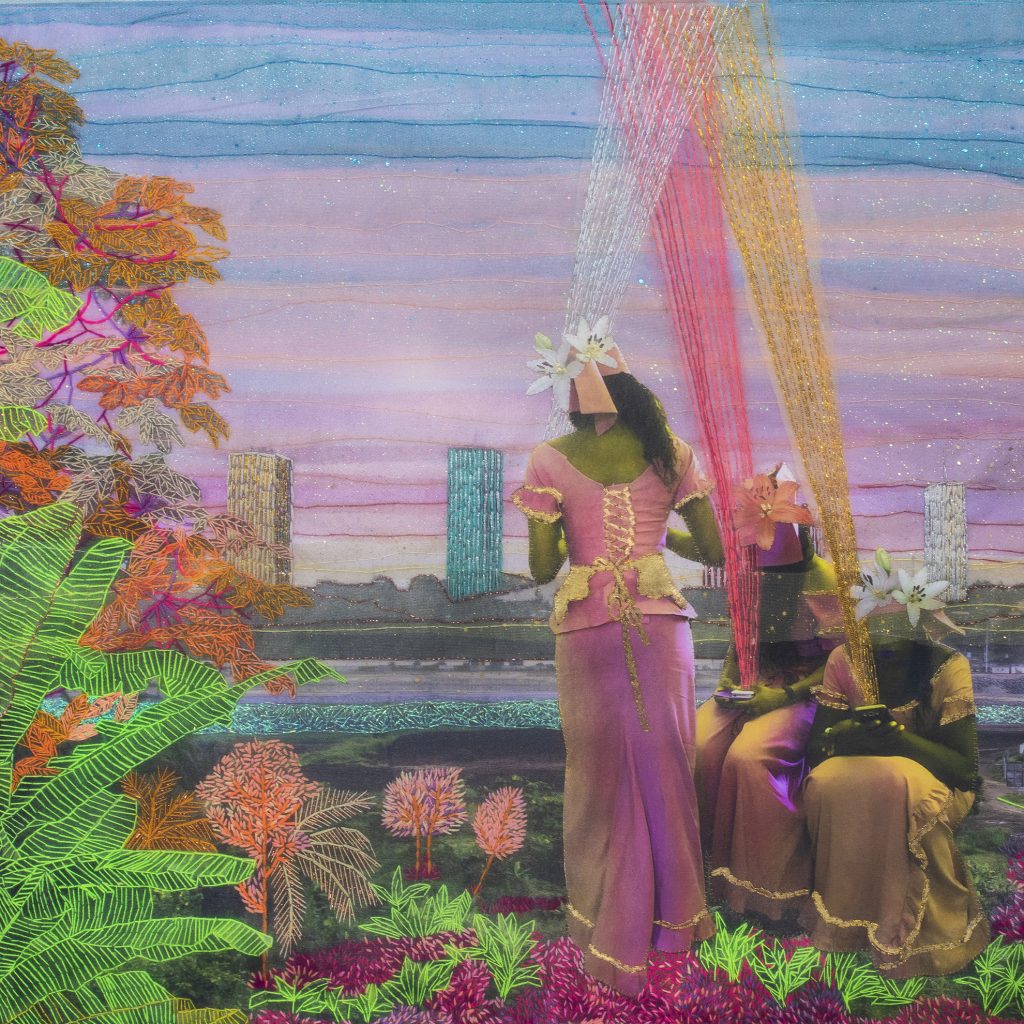

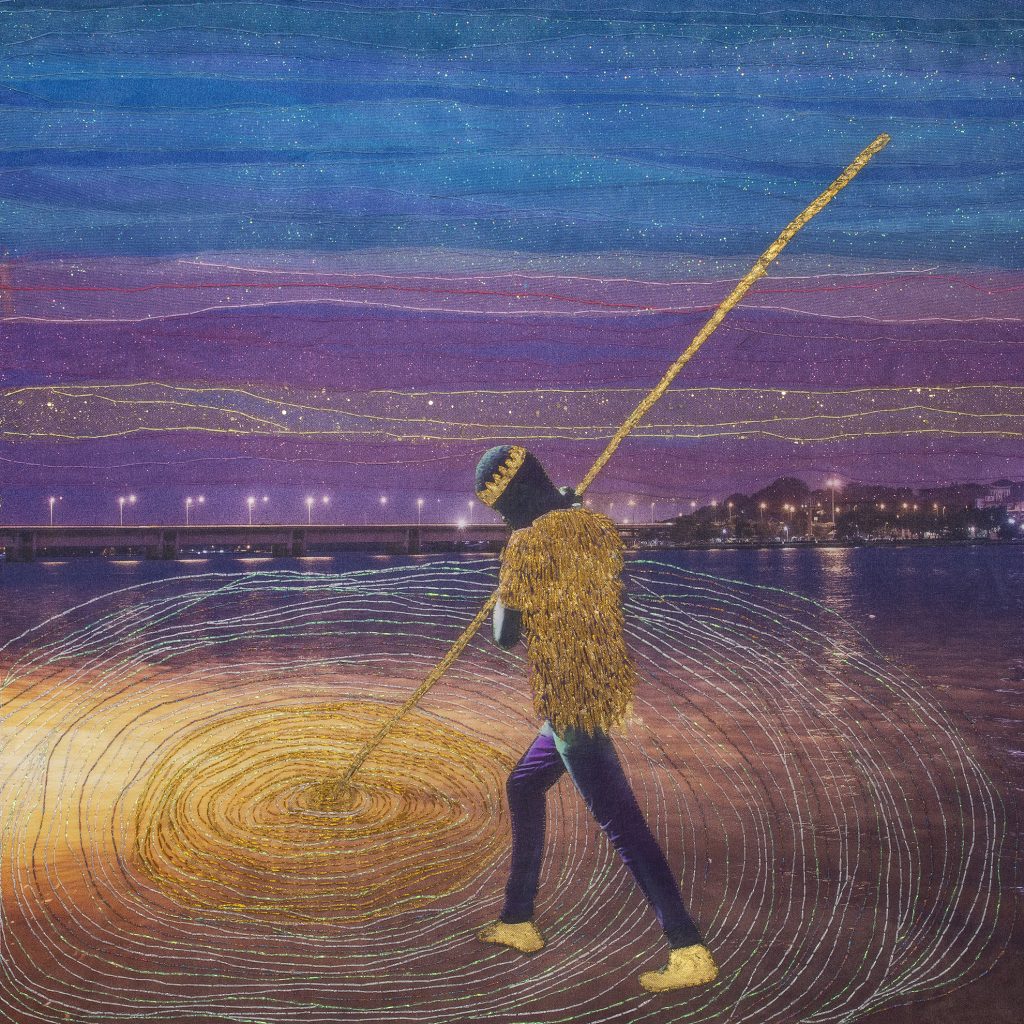

Joana Choumali, Ivorian photographer and visual artist, has tried not only to tell the wounds of her country but also to mend them, metaphorically, through a meticulous and careful embroidery work – with cotton, wool, lurex threads – on the photos she has taken and then printed on canvas. Ça va aller is the title of the project that, in November 2019, won her (first African artist), the prestigious Prix Pictet, the award created to draw attention to issues concerning sustainability. “Hope” was the theme of the eighth edition, a theme that Joana Choumali has masterfully interpreted and which, like a leitmotif, runs through her most recent works.

It was March 13, 2016 when a terrorist attack, claimed by Al-Quaeda, shook the calm and slow pace of Grand-Bassam, a tourist town located on the coast about fifty kilometers from Abidjan. The victims were 19 and the resonance was strong in a country like the Ivory Coast, still reminiscent of the trauma of the civil war that ended in 2011. Three weeks later the photographer left her home in Abidjan and to reach Grand Bassam, where she investigated the suffering and bewilderment that hovered in the place, shooting with her smartphone, more discreet than a camera. And then adding the embroidery to comfort, first of all, herself.

I reached her “virtually” to ask her some questions.

How did the idea to mix photography and embroidery came about? It is a very quiet and slow practice, and you said that you consider it “a sort of meditation”, a kind of automatic writing, linked to psychology and emotions; while photography sometimes is, in a way, a “quick” practice. Can you explain this very original approach?

My latest works are mixed media projects: a mix of digital photography and embroidery. The results are poetic, dreamy, unique pieces printed on textile. The mixed media practice responded to a need to touch and intervene physically on my photography. I started with my series Adorn by adding embroidery and beading on some pieces of embroidery that I then photographed again to do a digital collage. After this, I worked simultaneously on Translation , a series of diptychs that were exhibited at the Ivorian Pavillon at the 57th Venice Biennale. This was a project about migration. Then I worked on my series Ça va aller. I decided to shoot with my iPhone as if I was scanning the city, later I printed the photos on cotton canvas at the size of 24×24 cm and I embroidered directly on them. The small size allowed me to work from home, or from anywhere else. I love the meditative state in which you can immerse yourself while embroidering. It is a very specific feeling. Soothing. I use the same stitch for every canvas, this simple stitch as the ones that are used to repair a hole in a piece of fabric. Just like a healing process, the act of embroidering on my pictures has become engrained in my daily practice as a way to focus and concentrate, but also to project hope through my stitching gestures.

In the title, “Ça va aller”, there is a whole philosophy. Curiously, it reminds me what Italian people were saying during the days of the pandemic: “Andrà tutto bene” (everything will be all right.) But I think in every situation there may be different nuances. Why did you choose it? What were the sensations in these days, after the attack?

Yes, it is quite a similar state of mind. Like “Andrà tutto bene”, Ça va aller” translates to “It’s going to be fine,” a common phrase used by people in the Ivory Coast to casually reassure each other, even after a deeply traumatic event. I started the project less than a month after the March 2016 Grand-Bassam terrorist attack, when three gunmen opened fire at a beach resort an hour away from my home in Abidjan. Three weeks after the attacks, the atmosphere of the little town changed. The sadness was everywhere. A “saudade”, some kind of melancholy. Most of the pictures show people by themselves, walking in the streets, or just standing, sitting alone, lost in their thoughts. And empty places… The brightly colored threads serve as the sentiments I cannot express verbally, and a way to witness and acknowledge the trauma of the Grand-Bassam people. The very notion of observing this wounded city made me realize how full of life and joy it used to be. I recognized and captured a point of hope in these difficult times by reminding myself of what this space was before, by acknowledging the contrast of what it had become following the terrorist attack, and by visualizing, projecting in the aftermath, while accepting the fact that it may never be the same… It is an act of hope and resilience. For me, it translated into a creative process. I focused on observing the streets I photographed, then I filled these empty spaces with these colored threads as if it was in automatic scripture.

“Ça va aller” is linked to a specific and sad event. But you are still working on another beautiful series “Alba’hian”, in which you still use embroidery and also other techniques, like collage and quilting. It seems to be more positive than the previous one and even more full of hope, if possible. What is different for you, in the technique, in the subject in your sensations?

The symbolic of the morning light is often associated with hope, new beginnings, a rebirth. In my ongoing project, Alba’hian (it means “the first light of the day” in Agni language) I translate my experience of the dawn. Walking early in the morning, between 5 and 7 am, is a strong experience to me. it allows me to process my dreams and thoughts, all kind of emotions. I think that, often, an artist speaks about himself through his works. I explore my identity and my environment. What I want is to be able to start a conversation, a reflection that would be summarized by this sentence: “Who are we? Where are we going? Where do we come from?” For me, photography is an excellent medium or portal to get in touch with things that seem to be taken for granted, and so I invite people to think about it with me.

Actually, my current works are the results of a more personal, intimate process. I am planning to go further on this exploration of material and immaterial worlds that merge. My works are all about acceptance of who we are and exploring the subconscious. It is linked to my perception of the environment and the tacit connection I feel between the people I photograph and me. Also, the relationship with space, the landscape … the energy of a place. The non-verbal dialogue that can take place with the other and with an environment. I use my imagination. I focus on the meeting point between my emotions and how other people’s emotions contribute to this capture. When I shoot a picture, I feel like I also leave a part of myself. Art allows me to start this dialogue of hope with a place or a person. The act of photographing and then the act of embroidering for me is a logical extension, a response to any situation. Just being a witness to this situation can make me an actor in it. If it is not directly linked to specific events, Alba’hian is still incorporating my experience of the era I live in.

You alternate works of “mixed media”, like “Ça va aller”, to works of pure photography, especially stunning portraits series, like “Hââbré” or “Resilients”, that was also on exhibition at the Photolux Festival in 2015. It looks like now you are concentrating more on the mixed media approach, why? Have you planned some new photographic projects?

Yes, I would say that I gradually and naturally migrated from documentary digital photography to mixed media by following my instincts and by embracing that process. Now, I am focusing on mixed media. Since 2016, I have been working only on this technique. I am researching for a new project involving photography, embroidery and collage. I am interested in pushing the boundaries of photography by using digital photography and intervene on them manually afterwards.

Each piece of these projects is unique, which makes it more similar to art than photography, also because they have a “material side”…

Yes, each piece is unique. I am particularly drawn to the idea of spending a lot of time on a photograph that was shot in a snap.

Do you feel, in your career, you progressively detached from documentary photography to embrace a more conceptual approach? Would you define yours as a highly symbolic way to recreate reality?

Yes. But at the same time, I like to explore some social matters from another angle. Questioning myself with regards to my environment and observing society are still part of my process. I still like to open conversations through the symbolics and the conceptual approach I use in my work. To me, it is a different route but still the same goal.

Concepts like “resilience” and “hope” are strongly present in your work. Is it because of a positive vision of reality?

It is way more than a “positive vision of reality”. To me, if there is no hope, there is no strength to overcome hardships. Hope gives you the impulse to fight and improve situations. If you have no hope, how can you be resilient? How can you survive and strive?

Joana Choumali’s work is deeply linked to Africa and, in her photographic series, she has often dealt with topics such as identity, femininity and relationship with our body, observing how traditions interact with modernity. See, for example, the aforementioned Hââbré or Resilients projects. Also in Alba’hian, which comes to life during her morning walks, the Ivorian artist is “a witness to the energy of the continent that keeps her people going and shapes their lives”.

In her most recent journey, however, the artist not only transcends the boundaries of photography, but also those of her own land, managing, through her patient art overflowing with colours, to speak a truly universal language, capable of soothing, even if only in the short instant of vision, the wounds of a world that asks to be rescued. And allowing us to try and imagine a different future.

All images: © Joana Choumali

July 9, 2020