by Dario Orlandi

_

In his latest book, Martino Marangoni retraces his relationship with the American metropolis which started in the 50s and never stopped. As an Italian-American, Marangoni discovered New York as a child, exploring it with a Kodak Brownie. He returned there in his twenties for a term of study at Pratt University which then became a three-year period and a life’s work. Photographer, curator, professor of photography, Marangoni has trained generations of Italian and foreign photographers in his Studio Foundation in Florence. As an author, he has exhibited in prestigious Italian and international locations. We interviewed him to know more about his New York.

The book opens with the first shots you have made as a young boy with a Kodak Brownie. Despite the precociousness of these photographs, do you still find something of yourself in those pictures today?

These are photos I’ve taken, so they are part of my story. The only difference is that at the time I was a “tabula rasa”, I did not know anything about the history and technique of photography. Perhaps, paradoxically, those images represent me more than others!

I am interested in the relationship between knowledge and instinct in the creative process. Sometimes the more you know, the more you limit yourself. Sometimes the primary instinct is the deepest and the most genuine one… When you see those first shots, do you think that way of looking at things remained in your photographs afterwards?

A photograph is a bit like pointing your finger at what you see and what strikes your heart. It’s a bit like saying “Wow”! Look at that!”; whether it’s a skyscraper, a tree, a person, when you take a picture it’s because you think: “Look what’s in front of me! I want to capture it!”. My answer to that particular moment was that image.

In the early adult works you have played with street photography, experimenting with different stylistic solutions that coexist harmoniously in the sequences of the book: from the geometries of images shot from above, to the wide-angle tensions of fast street looks, to the tale of society in its daily life: a varied but consistent mosaic. Is style a limit from which the authors must know how to break free in order to invent another one generated by the mixture of styles?

I do not think there is a rule that applies to everyone. I find it limiting to try and simplify the question of style by saying what is right and what is wrong: in some cases the serial works function because they need a consistent and constant approach, but this cannot become the only way, especially if the public is then not hit with a message or an emotion. It all depends on the result.

In my book, the choice to mix genres depends on the desire to describe a long journey, a sort of time travel as in the films of David Lynch: jumping from the past to the future in order to confuse, to make the story more interesting and contemporary.

In the ’80s with the transition to the medium format your language takes a more meditated direction, made of broad views with minimal human presence. How has your perception of the city changed after a decade and with a different medium?

At that time I’d started working on landscape photography commissions and I developed a more attentive eye towards the analysis of the territory. With the medium format I acquired a more detached point of view, working at a slower pace.

In New York, as a result, I focused on this way of looking, also because the human aspect of the city in those years was less interesting for me; New York had changed. My subjects became the buildings, for which I needed higher and more distant points of view.

In your images the skyscrapers are reflected one in the other: an infinite kaleidoscope, a beautiful visual metaphor of an endless city. Your New York is in continuous transformation, vigorous and vibrant with metallic light, ever changing; very different from the “Nonni’s Paradiso” so bound to the cycle of the seasons…

The motivation behind my images is always autobiographical, those you mentioned are the opposite poles of my family identity. My parents were one from Florence and the other from New York, in my life there have always been two opposing realities that I had to try to reconcile, not only from a cultural point of view, but also geographically: on the one hand the countryside with the olive trees, on the other the skyscrapers. Even my photographic activity was born between these two extremes: I started among the olive trees and I continued throughout my life, the same is true for New York.

The World Trade Center: the construction of a myth, its destruction by the hands of terrorism, the rebirth from its own ashes as a sort of contemporary phoenix. How has the perception that New Yorkers have of themselves and of the city changed through the experience of this tragic event?

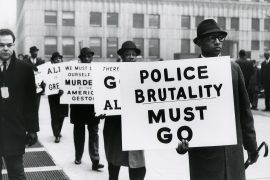

The city is constantly changing: relations between the city and the people and between the individuals change. There is no New Yorker: there are people living in New York. Some have been there for 100 years, some for 10; even my father, who arrived there in 1936, within a very short time became a New Yorker. This is the inclusive and welcoming capacity of the United States, of

New York in particular. What unites New Yorkers is the great love for the city, the ability to interact and integrate, to communicate and be together accepting with great openness the people who arrive. It’s a very hard city, if you want to stay you have to become determined and work hard; there is, however, a strong sense of humanity, of love for the city and for everyday life. During the attack on the Towers I felt great admiration for the composed, mature and civil way of participating in the pain; It was moving to see how the city reacted in a generous and surprisingly quiet way: I never saw anyone panicking.

After 20 years the city has changed because NY always changes, or is there a before and after the Twin Towers?

All over the world there is a before and after the Twin Towers, it is a pivotal event in the history of humanity, it has changed contemporary history. But New York has not been intimidated, it reacted, it has moved on. Indeed, it has matured! I believe that what has been built now is far more beautiful and liveable than the grey buildings of the ’70s, the exclusive symbol of economic power. Now there is a park, the Memorial for the victims, the Calatrava station, places where you can meet up or just pass by; the city has taken the opportunity to transform itself, becoming a more civil and inclusive place.

Your work is the experience of a city that is partly yours, but not completely, a city where you return on a regular basis. In the book write: “Every year I look forward to my next trip. […] Would I feel the same way if I actually lived there? Probably not. “What does it mean to belong to two cities? To have two roots or to have none?

This has always been the destiny of my life. Even when I was a kid at school, they saw me as a stranger because I dressed differently with the clothes my American grandparents sent me, or because I made some mistakes when speaking, as foreigners do. Living the cultures of two countries I had to face some difficulties, both here and there, because you have a point of view based on two different worlds and jump from one to another. It’s certainly an asset, I think I’m lucky to have had this chance; at the same time, however, this condition complicates things a bit…

From the Brownie to the smartphone: in the last images of the skyscrapers you have found the same amazed look of your child self, that, in reality, it never completely leaves your works…

Experimentation has always been a trigger for me: going from black and white to color, changing formats, changing the way we look in the lens, all this is part of the desire not to be bound to a sole way of building the image. I try to tell the emotion I feel in exploring places that amaze me by means that are also able to amaze me. Using a new camera produces emotions similar to those that a child experiences when he explores something unknown.

So the technologies change, the way of looking at things changes, but the curiosity for playing and experimenting doesn’t?

Exactly. Changing instruments forces you to reformulate your approach to the outside world, it requires you to treat the subject with renewed amazement. And I do not want to lose the freshness, the ability to look at things with pure eyes.

The book:

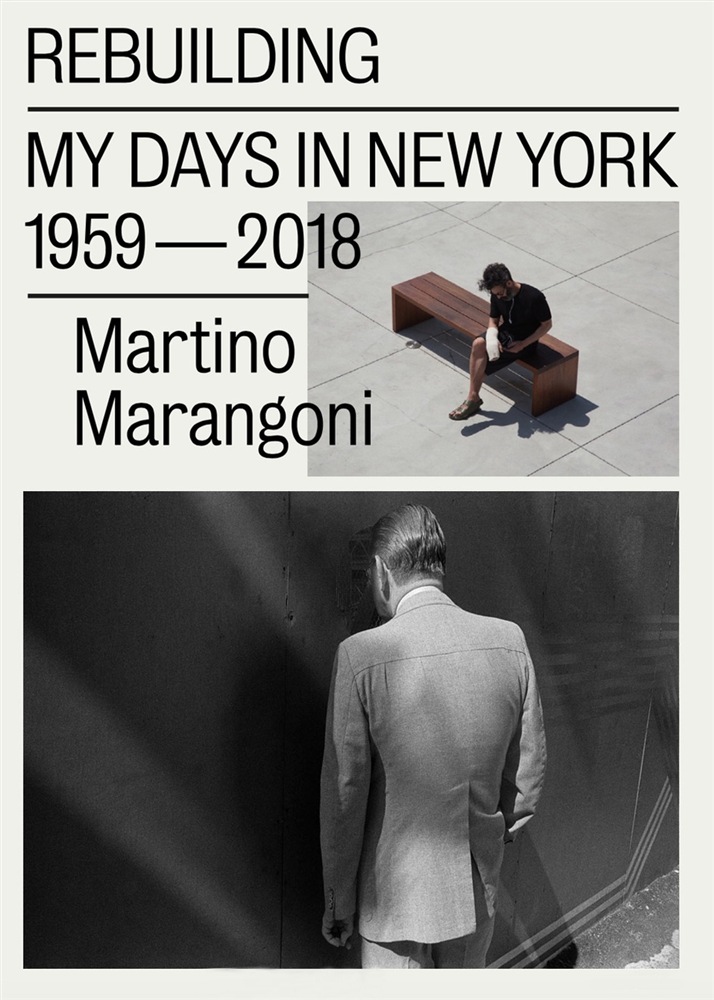

Martino Marangoni

Rebuilding my days in New York, 1959-2018

the Eriskay Connection/Postcart, 2018

All images: © Martino Marangoni

February 18, 2019