by Claudia Stritof

_

Industry at its best is the intersection of science and art.

Edwin Land

Edwin Land, second only to Thomas Edison in number of patents, was defined as the last of the great geniuses for his scientific innovations, including the invention of the first polarizing sheet, made of a plastic film studded with numerous herapatite crystals; an idea that brought about a real revolution in various fields, including photography, with the birth of the Polaroid.

Born in Connecticut on May 7, 1909, Edwin Land enrolled at Harvard University in 1926 but, already by the fall semester, he was spending long hours in the New York Public Library to consult books on physics, optics and chemistry. Immersed in his solitary readings, he got blown away by Robert W. Wood’s Physical Optics, the masterpiece of the important American physicist who discovered Black light, better known as Wood’s Light.

The university environment was distracting for him, while inside the library no one would dictate time and schedules: as Land himself said, “you don’t want to be disturbed. You want to be free to think not for an hour or three, but for two days or two weeks, if possible, without interruption” and so he did until, in 1932, together with physics professor George W. Wheelwright III, he started his first company called Land-Wheelwright Laboratories.

It is the economics historian Harold Livesay who emphasizes how Land supported harmony and perfect symbiosis between “work, virtue, profit, beauty, technology and progress”; in fact, from a very early age, he developed a philanthropic idea of industrialism, taking into account the physical and mental well-being of his employees, who needed “comfortable conditions” and “intensive concentration” to develop their inventions. After all, even the polarized sheet was born “for the public welfare”, a solution against the danger of being blinded by car lights at night.

Land started a collaboration with General Motors and with Eastman Kodak for the creation of filters for cameras, with the American Optical Company for the production of polarized lenses for sunglasses and, last but not least, he also invented the antiglare desk lamp with designer Walter Dorwin Teague, future creator of some of the most famous Polaroid cameras. Thanks to Land’s charisma and his team of engineers and researchers, the company increased its turnover so much that, in 1937 the Polaroid Corporation saw the light, despite the dark times the imminent war was bringing about.

Vannevar Bush, former vice president of engineering at MIT, asked them for help in the war effort, so during his Christmas speech in 1942, Land stated “we now exist for one purpose: to win this war”, and the aim the company turned towards that direction. Working with the National Defense Research Committee, Polaroid engineers created a wide range of products: “polarizing filters for gunsights, binoculars, periscopes, rangefinders and infrared night vision devices”; without forgetting that – as reported in the catalog of the exhibition curated by Melissa Banta, At the intersection of science & art – “another contribution from Polaroid […] was the production of quinine”, extracted from the bark of a tropical tree in Java, whose production was interrupted due to the occupation of the Japanese troops. Thanks to the work of Dr. Robert Burns Woodward of MIT and Dr. William von Eggers Doering, Polaroid sponsored the discovery of synthetic quinine alternative to the natural one, precious for the treatment of malaria.

It was then 1943 and, as Land himself recalls, “I remember a sunny day of vacation in Santa Fe, New Mexico, when my daughter asked me why she couldn’t immediately see the photo I had just taken of her. While walking through that fascinating city, I wanted to solve the riddle she had posed to me. Within an hour, the camera, film and operation became so clear to me that with a great sense of excitement I hurried to the location of Donald Brown, our patent attorney”.

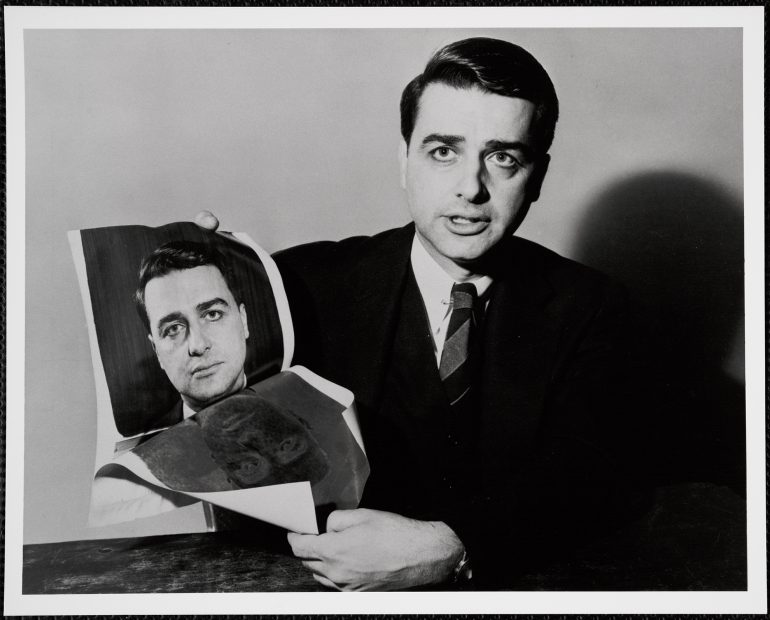

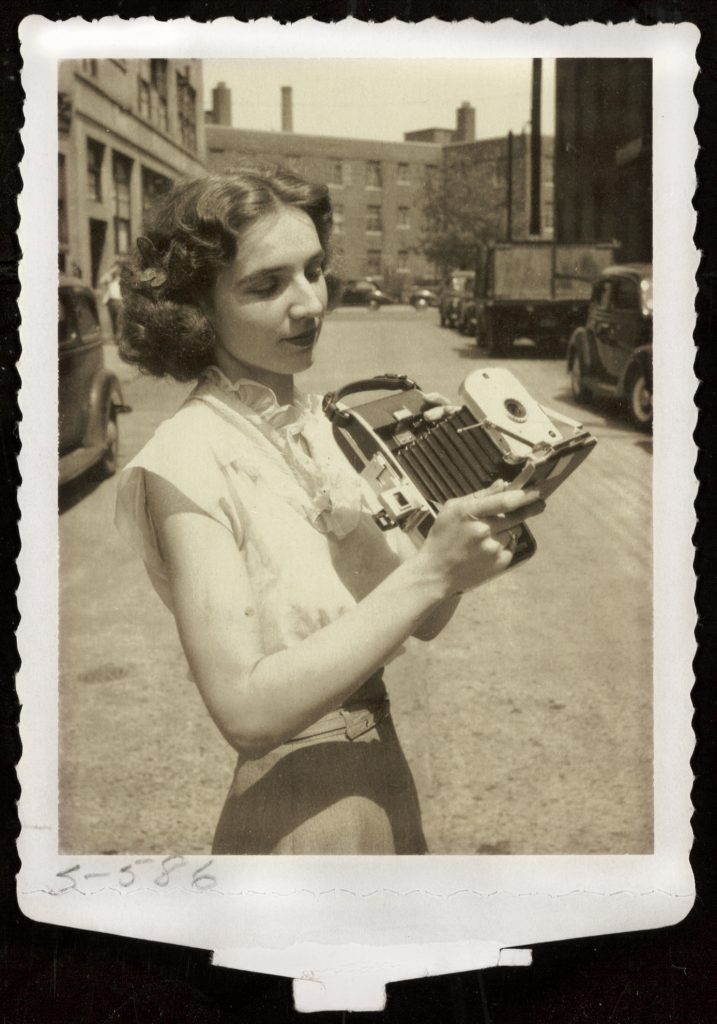

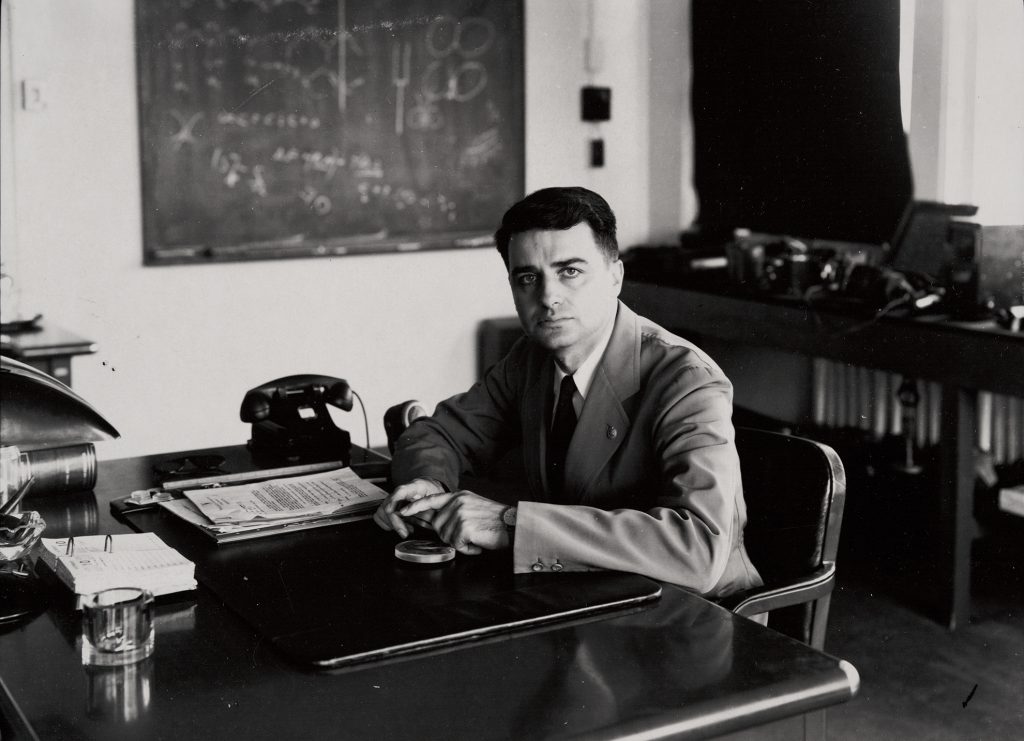

Between 1944 and 1945 the company launched a special project dedicated to instant photography, SX-70, of which in addition to the official documents, the Polaroid archives also store the first – and numerous – print tests made to try out films and cameras in different situations. The subjects were the Polaroid Corporation employees themselves, Edwin Land posing in his office, the technicians at work; portraits of their families, as well as street scenes captured around the building, cars and pets.

On February 21, 1947, during a meeting of the Optical Society of America in New York City, Land presented the first Polaroid camera, demonstrating how it worked with the creation of a portrait of himself; a photographic sequence that has now become famous and that sees him at first serious and concentrated, then smiling at the success of the shot. On November 26, 1948, the Polaroid Land Camera, Model 95, went on sale, not without fear for company turnover, at Jordan Marsh, the Boston department store, which unexpectedly had them quickly sold out.

Simple to use and immediate in printing, the Polaroid was engaging and friendly. It brought people together in the shot, but also in the moment of development, creating unique, playful and “amateurish” images. And it is precisely about its supposed amateurism, that the author Christopher Bonanos in Instant: The Story of Polaroid, states: “Land immediately took a big step to counter this idea” and in fact “he met an expert who in the years to come has redefined what Polaroid photography could be”. The expert was the great photographer Ansel Adams, who became the company’s consultant at the end of the Forties.

The marriage between art and science had been celebrated, so much so that it became the “cornerstone of his research-based industrial enterprise”, a goal achieved thanks to Edwin Land’s foresight; a curious person who firmly believed in the impossible and was naturally optimistic, as well as gifted with great artistic sensitivity and ingenuity.

He used to repeat: “if something is worth doing, then it is better to do it in excess” and he did exactly that; extraordinary example of a man who has changed an already written story, starting a new, great era.

Courtesy Polaroid Corporation records, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

July 1, 2021